Sandwich theory, as a discipline in its own right, began almost two hundred years after the foodstuff itself, when Gödel published his seminal “Incompleteness Theorem of Sandwiches” (Die Sammichunvollständigkeitssatz). A lesser-known precursor of his famous theorem, it asserts that, for any axiomatic system of sandwich construction, there exists at least one edible sandwich that cannot be constructed within the rules of the system: anomalies that he called “recursive sandwiches.”

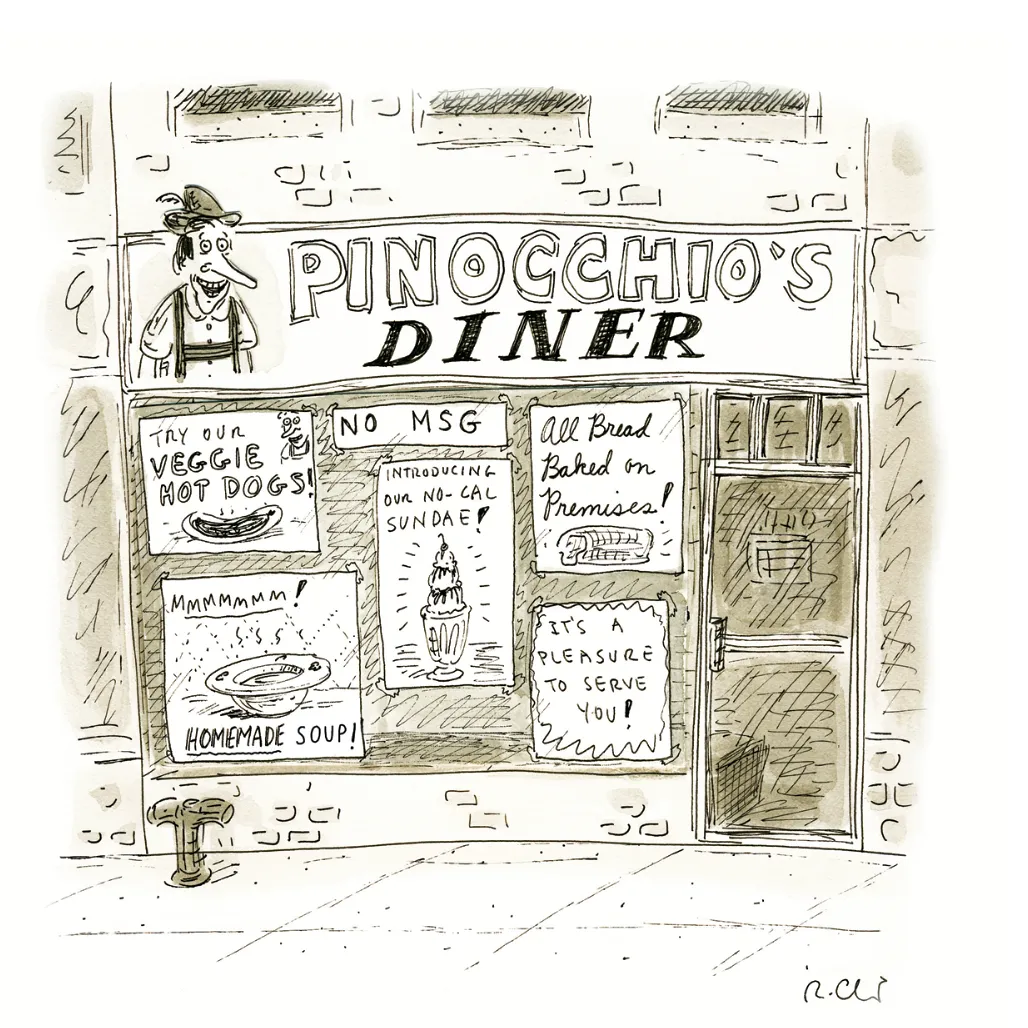

Gödel never claimed to be a chef, and he was famously chary of making claims for the practical significance of sandwich recursivity, but an explosion of culinary research quickly discovered two real-world examples of these anomalies: the bread sandwich — a sandwich whose only filling is another slice of bread — and, more adventurously, the sandwich sandwich.1

That’s when things got interesting. Building on the link between sandwich theory and set theory, several of Gödel’s protégés also posited the (purely theoretical) existence of a null sandwich and a universal sandwich. The null sandwich consists entirely of two slices of bread, possibly with a thin spread of mayo, and was accepted immediately by the academic and culinary communities. The universal sandwich, however, met with surprisingly vociferous resistance.

Only the most hard-line theorists were willing to admit of a sandwich that contains everything that exists, except itself. In fact, the very possibility of its existence was denied until almost thirty years later, when a brilliant young graduate student at Princeton actually made one.

Mort Kummelstein had originally set the sandwich world on its head with his groundbreaking 1976 Inedibility Hypothesis. Published anonymously, “Must Sandwiches Be Food?” posited the rock sandwich, the lightbulb sandwich, and the Volkswagen sandwich, sparking a series of still-unresolved controversies that changed the face of edible mathematics forever.

An unnamed letter-writer to the Journal of Comparative Mastication sniped that, under Kummelstein’s hypothesis, one could conceivably place two slices of pumpernickel antipodally in Paraguay and Taiwan, creating an Earth sandwich. Professor Jan Deutsch of Tübingen took it one step further, suggesting that, if we were to accept inedibility, nothing would prevent the construction of an “air sandwich,” consisting only of two slices of seven-grain whole wheat pointed in each other’s general direction.

Unbeknownst to him, Deutsch’s facetious suggestion had paved the way for the greatest paradigm shift since the invention of the sandwich itself. Kummelstein and his advisor, Professor Charlotte Stein, accepted the reductio, and at CUNY Graduate Center’s 1978 conference on cognitive edibility, they set the sandwich world on its head by placing two pieces of bread together, but facing away from each other. The repercussions of this bold and unexpected move were felt in every area of public life, and it was immediately deemed a threat to national security by the Carter administration.

To date no one has been able to conclusively disprove Kummelstein-Stein, and more than one thinker has been driven mad by the effort. But thanks in large part to their experimentation, sandwich theory continues to move forward, and remains a vibrant field of graduate research. (For undergraduate study, it is generally folded into either the sociology department or the hospitality school.) ◊

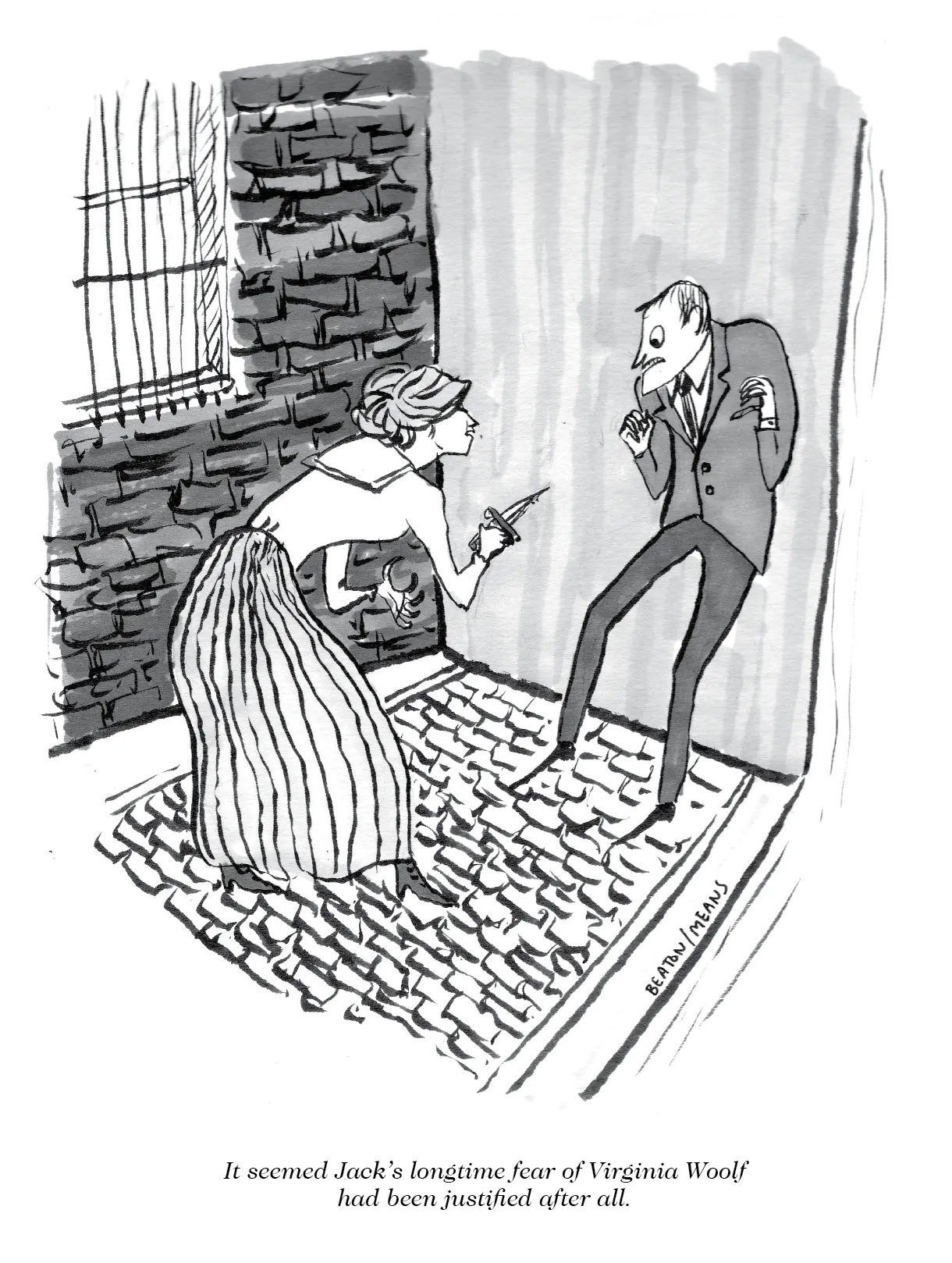

SAM MEANS was a writer for the Netflix series Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt. Previously, he wrote for The Daily Show, 30 Rock, and Parks & Recreation, and drew cartoons for The New Yorker. His dog is named Myrna.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR professes history at Northwestern University. He can do three (3) pull-ups, knows the lyrics to many folk songs, and still has all of his teeth.