Note: This piece was initially printed in The American Bystander Issue 19. We miss Sean Kelly very much. Happy Saint Patrick’s Day to all who observe.

The American Bystander's Viral Load is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Father Timothy Gallagher, SJ, Prefect of Studies, was concerned about my chronic non-progress in mathematics. “These are the grades of a stupid person,” he said, “but you aren’t that stupid.“ (Arithmophobia or numerophobia is a diagnosable and treatable anxiety disorder, but neither my teachers nor I knew that then. We were agreed that the difficulty arose from my reluctance to apply myself.)

Mrs. Huber, Father Gallagher said, was a widow of the parish who lived nearby. Her twin sons had graduated from Xavier some time ago and were now in Munich pursuing advanced degrees in quantum mechanics. She had generously agreed to tutor me in algebra, twice a week, in her home. I was permitted to leave campus and excused from 5 o’clock study hall, but was to be back by 6:30, in time for dinner in the refectory.

The lowest temperature ever recorded in the city of Montreal was –36°F on Tuesday, January 15, 1957, the date of my first math session with Frau Huber.

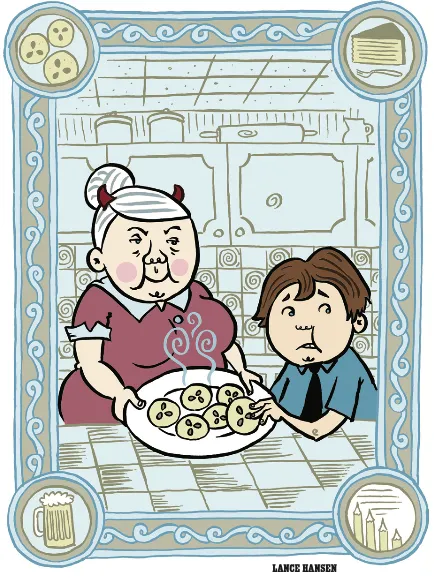

Mrs. Santa Claus opened the door: a plump, smiling woman wearing rimless specs, her grey hair in a bun, eagerly gesturing for me to enter.

In the front hall I took off my mitts, boots, hat, scarf, and coat. Apparently, Mrs. Claus liked to keep her home cozy and warm. I experienced a temperature swing of nearly 100 degrees.

I could smell newly sharpened pencils. Six of them were lined up on the dining room table, exactly parallel to several pads of yellow, lined foolscap. There were two chairs at the table. Frau Huber took one and gestured for me to sit beside her. With one of the pencils she printed an equation on a page, in letters and numbers so regular they looked typeset. “Ach so, ach so, make for me this problem.” I stared at the page. I picked up a pencil. My natural obtuseness kicked in. I shook my head and carefully put the pencil down.

She tried. She was patient. She showed me what to do. Then showed me again. Eventually I wrote down what she had just written as if I had come up with it on my own in a flash of comprehension.

At 6:15, at the door, she handed me a brown paper bag. “Elisenlebkuchen from Christmas left over,” she said.

On the way back to school, at 36 below, I ate a dozen nutty, sweet, German gingerbread cookies.

Thursday afternoon we were back at the table with the blank yellow pads and dangerously sharp pencils. “Ach so, ach so, make for me this problem.”

I said, “Thank you for the cookies by the way, they were delicious.”

She smiled. “In Bavaria to make Elisenlebkuchen we use Hostien Oblaten—what you are calling holy communion host.”

I gasped, I guess I looked shocked. Was I involved in some kind of Black Mass?

Frau Huber laughed. “Not oblaten blessed by a priest, natürlich, just ordinary wafer.”

She put down her pencil. “I think your trouble with equations is you are hungry from school food, too hungry to concentrate. Perhaps we try an experiment.”

Prinzregententorte is a chocolate layer cake. The eight layers, I learned, represent the eight administrative districts of Bavaria. Some minutes later I could confirm, scientifically speaking, that Prinzregententorte has no effect whatever on arithmophobia. But as far as I was concerned our experiment had been a smashing success.

Tuesdays and Thursdays thereafter I made almost no progress in algebra but I acquired a deep appreciation of Bavarian cuisine.

While I ate, she took it upon herself to disabuse me of my (she presumed) prejudice against Germans. She herself was from Bayern—“what you say Bavaria”—in the south. “It is Prussians from the North that are mindless criminals, cold like robots. In Bavaria we call all bad people Saupreussen. It means ‘Prussian lady pigs.’ Hitler was a Saupreussen.”

According to Frau Huber, Bavarians work hard but also play hard. “In the city of Dingolfing the BMW factory makes annually 270,000 of the world’s best auto cars but also in München is taking place Oktoberfest, the world’s biggest, best party.”

Frau Huber served me not any old wienerschnitzel but altbayerisches schnitzel, and not ordinary sauerkraut but Bayrisch Kraut. On one unforgettable occasion, she prepared Schweinshaxe, which is roasted pig knuckle with gravy and dumplings, fluffy clouds that she called Semmel Knoedel.

Her hometown, she revealed, was Passau, where three rivers meet, one of them the Danube. Her husband, the late Herr Doctor Karl Huber, had been on the faculty of the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. He was a theoretical physicist, an associate of Werner Heisenberg. Did I know Doctor Heisenberg?

Karl saw that Nazi persecution of Catholics was only a matter of time, and so in 1935 packed up his wife and twins and came here to Canada. Frau Huber assured me that this miracle was accomplished thanks to the intercession of the Schwarze Madonna, a black statue of the Blessed Virgin venerated in a shrine at Altötting.

She assured me that Bavarian beer is the very best, both hefeweizen and ungespundet-hefetrüb. She never offered me a foaming stein, but now that we had abandoned quadratic equations entirely, we achieved a state of Gemütlichkeit, an impossible to translate, exclusively Bavarian condition, she told me, meaning cheerfulness, friendliness, coziness.

For disciplinary reasons I was grounded for most of that winter, but still permitted to leave the campus for my alleged algebra tutoring sessions with Frau Huber.

Lent had begun in the first week in March, so on this Tuesday I knew better than to expect much in the way of edible treats. When I rang the bell, she answered the door abruptly, almost violently. She was clearly very angry about something. I hoped it wasn’t me. I followed her inside. She slapped a newspaper on the table. “Look, look, it starts again.”

The headline blared: “Israeli troops leave Egypt. Suez Canal reopens.”

“What starts again?” I said. “I’m sorry, I don’t understand.”

“Zey want another war.”

“Who does?”

“Who has started every war?”

She had me there, I had to admit. “Who?”

“Ze Chews!”

I had not been previously exposed to this comprehensive explanation of world history.

I said, “Wait. Do you mean the Jews started every war? What about, um, say, the American Civil War?”

“ ABRAHAM Lincoln,” she explained.

I did not personally know any Jews, and though I’d read The Merchant of Venice, I had failed to acquire my fair share of traditional lumpen Catholic anti-Semitism. I was sure I had to terminate my gustatory sessions with the Frau, but I had to find a way to do it without hurting her feelings, because I really liked her.

Father Gallagher resolved my moral dilemma. That very Friday, my class had been subjected to a mid-term algebra exam. On Monday I was summoned to the Prefect’s office. He sat behind his desk, scowling down at a blue exam book. “Kelly, I’ve canceled your lessons with Mrs. Huber. It was worth a try,” he said sadly, “but it seems you really are that stupid.”

SEAN KELLY hopes to become a real writer someday. He has nine grand daughters, all of whom are better at algebra than he is.

The American Bystander's Viral Load is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.