It’s Friday afternoon, which means it’s time for me to answer reader questions.

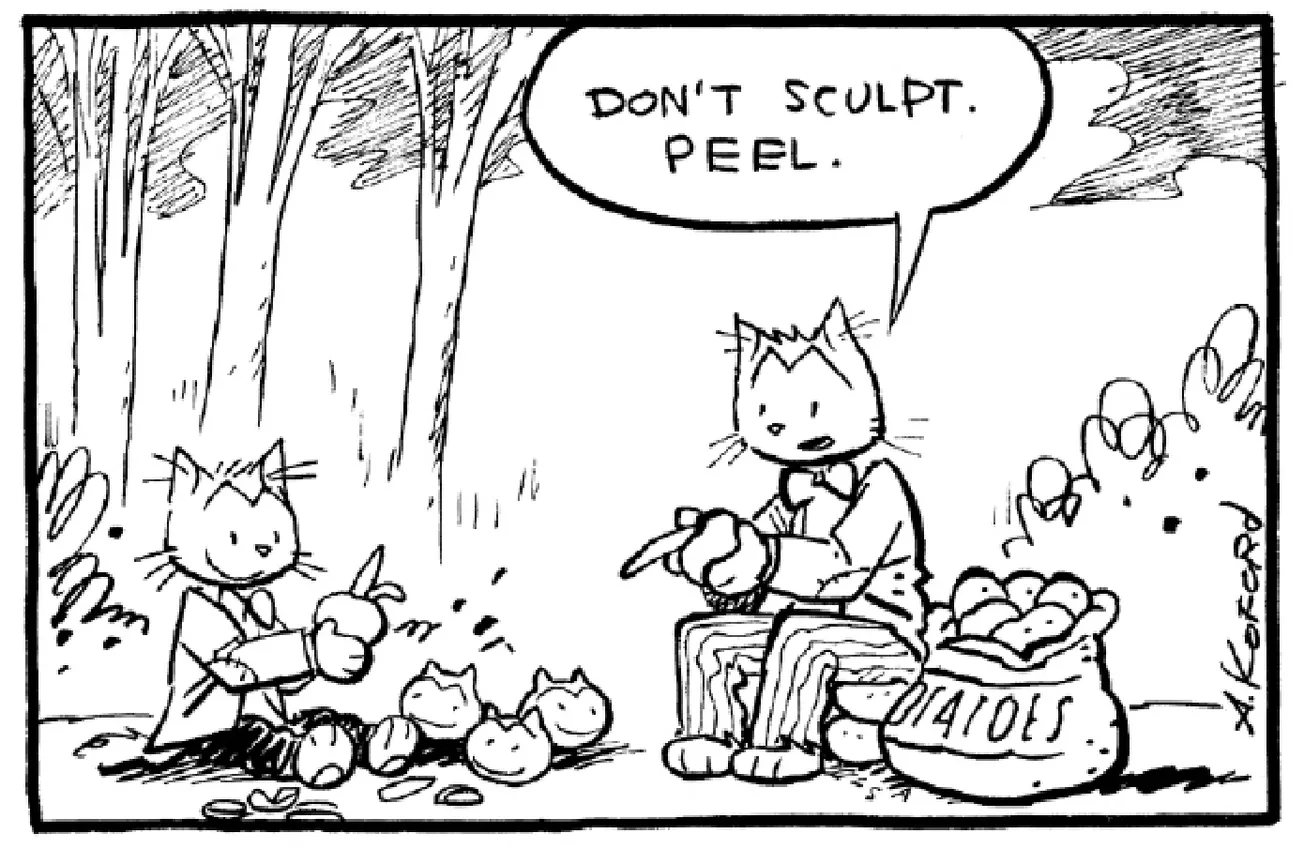

It is also, apparently, time for me to power through a whole bag of Pepperidge Farm Gingerman cookies. “The Gingerman” is my upcoming Blumhouse horror flick; I won’t get into the plot because I want you to see it, but suffice to say, adult-onset diabetes figures prominently.

Nebbish Inquirer writes, “MG, how important is comedy during times of extreme strife in the world?”

Nebbish, my gut says that the world’s Strife-ometer remains pretty constant. There are obviously outlier events—The Battle of the Somme, the release of Godfather III—but in general there’s a lot of sorrow and a lot of joy happening all the time. Strife is the stuff of drama, so our history is arranged around it, and negativity bias is an evolutionary tool that keeps humans alive. Plus, it makes us feel kinda tough to imagine we’re really “in the shit.”

HUMAN: “I’m a human, the only animal burdened with the consciousness of their own mortality.”

GAZELLE: “Sorry, I couldn’t hear you over the sound of my pelvis being crushed.”

LION: “Sorry, gazelle, your blood’s the only water I’ve had for four days.”

TERMITE: “Did someone say something? The gazelle was stepping on me.”

TREE: “Did you know I can feel a sensation somewhat like pain? Termites suck.”

But for the purposes of this conversation, let’s say that there are definitely times of extreme strife. How important is comedy?

Okay. As we all know, angry, sad, powerless or depressed (a/s/p/d) people use comedy to make themselves feel better—and this is a good thing, if it is the only alternative. If you are an soldier trapped in a trench at the Somme, by all means start a humor magazine. It is perfectly reasonable to be a/s/p/d in this case, you’d be crazy if you weren’t, and since you have no way of extricating yourself from what is causing you to be a/s/p/d, comedy is a wonderful wholesome healthy release.

It is better to crack a joke than slug someone. It is better, perhaps, to crack a joke than eat another Gingerman, as I just did.

But there are times when comedy is really not helpful, and I want to pause on this because you seldom hear this viewpoint, especially from within the comedy biz. Some people—many people—substitute comedy for actual mental health care, and that’s not good, especially if what we’re calling “comedy” is actually sneaky trauma-sharing. Just like fantasy football is a socially acceptable way for some men to be assholes, comedy can be a way for a person to externalize, and thus avoid, something they should really be trying to fix, resolve or move on from. This possibility goes up the more central “loving comedy” or “being funny” is to a person’s identity; and if a person does comedy professionally, warning bells should ring. One of my real sources of tension as a Comedy Professional (dingdingding) has been a gnawing sense that it doesn’t seem to help. Ethically, it’s not great to gather a/s/p/d people together, and keep them stuck in a/s/p/d to make money.

Let me be clear: it’s okay to have those feelings. People feel how they feel. But it’s not okay to wrap a/s/p/d in a bunch of jokes, and make people who might otherwise be happy, a/s/p/d. To make them feel that they are somehow better, smarter, or more honest to feel that way. That a/s/p/d is the Truth.

One of the worst developments of modern comedy has been the cultural conflation of addiction and other difficult states with the impulse to generate laughter. They are two separate things, and the mixing of them is classic addict-thinking—“If you want me at my best, you have to take me at my worst.” Prior to the 1950s—in other words, prior to the introduction of a whole panoply of recreational drugs into mainstream society—the Pagliacci syndrome existed, but it was not the dominant way that our culture looked at comedy. His Tramp might be sad at times, but Chaplin was not considered sad as a person. The Marx Brothers, as people, did not embody the essential meaninglessness of the human condition. Nobody pondered what dark mechanism drove Henny Youngman.

After the “sick” comics—and it must be said, the Holocaust and the Bomb—this all changed. Comedy became important and to be important it had to be more than just laffs. Lenny Bruce has been remembered and revered in a way Mort Sahl has not, because he was a drug addict with an addict’s glamor and capacity to titillate. Del Close, Belushi, Pryor, and on and on, so now when John Mulaney trots out a special about his addiction, nobody bats an eyelash. I’m not taking Mulaney’s inventory (not least because I haven’t watched the special), but I cannot help but wonder whether his life would be better had he turned to something other than comedy to cope with it. As he now knows, joke-making is too often putting a band-aid on a head wound. And when someone’s paying you to do it? It’s even harder to kick.

So, with all those caveats in mind, I would say that if you are personally having to eat a shit sandwich—and you are not Charles Laughton, who was apparently into that sort of thing—comedy can be a great temporary comfort. Both comedy from others, and jokes you make yourself. But as a lifestyle? Don’t. It numbs you.

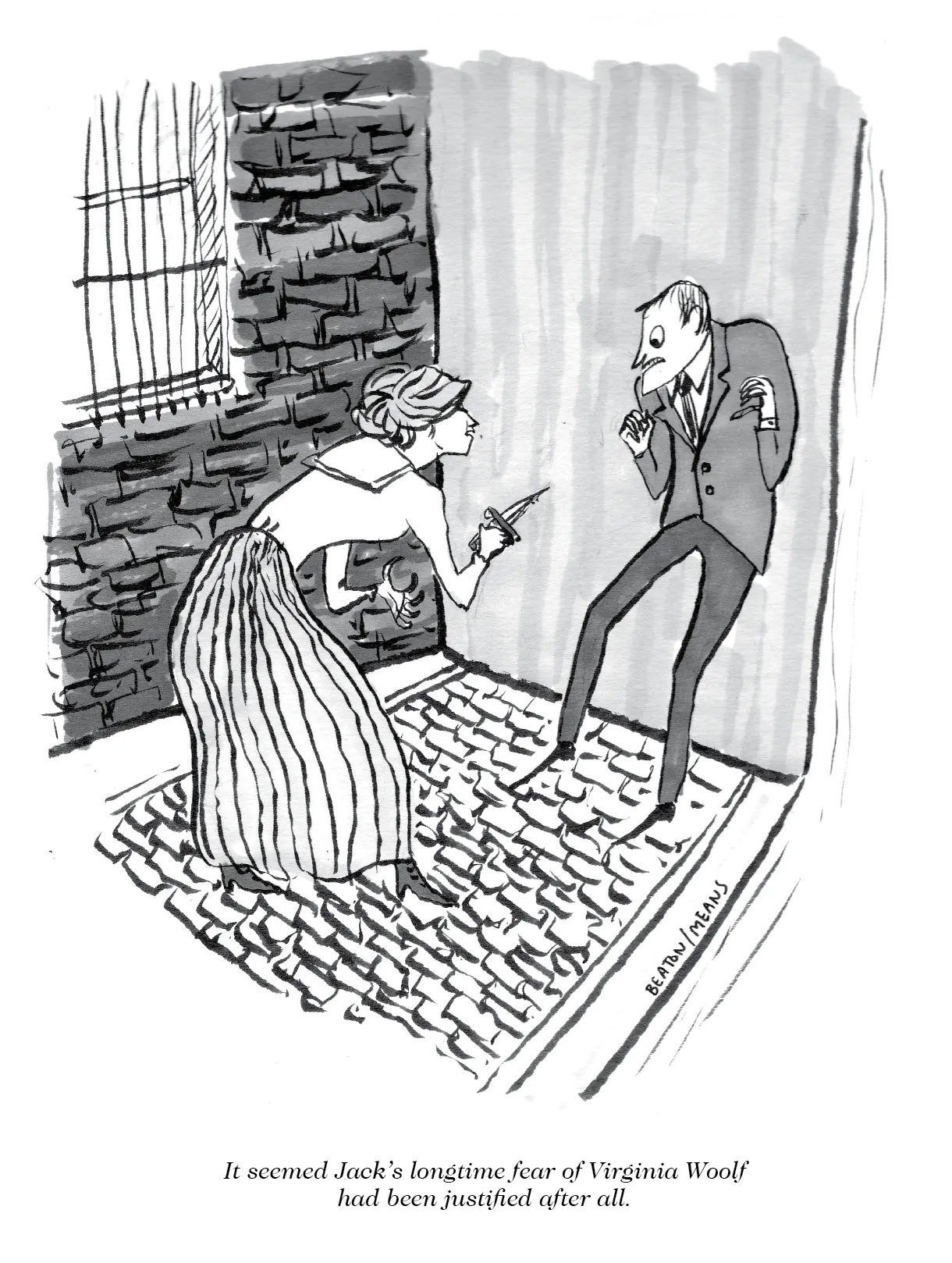

Comedy as pleasure is wonderful; comedy as anesthetic is terrible because you can’t move. You can’t make anything better for yourself or others when you’re numbed out. Not for nothing has our slide into political chaos—the re-emergence of actual, honest-to-Adolf fascism—been accompanied by jokes, jokes, jokes. When we crack wise on X, are we sensibly reacting to an unavoidable catastrophe? Or are we allowing it to happen because we’d rather joke—comment—be passive—than act?

If there’s one thing about Fascists, it’s that they have no sense of humor. And that may be a clue to the rest of us. We may have to stop joking, if we want to avoid another Godfather III.

Every Friday, The American Bystander’s Editor & Publisher Michael Gerber answers questions from readers, like he knows anything. To add your question to the pile, email publisher@americanbystander.org and put “Question” in the subject line.