Before I begin, I want to humbly ask for your help: I have never learned to love college basketball. Like hockey, so many people dig college basketball so intensely, there must be something there to enjoy. I have one friend who even nursed a long-term crush on the head coach of Villanova. So if anyone can help lead me to this new interest, holler back in the comments. Thank you.

ALSO, my humor magazine The American Bystander is running a special Holiday Sale: seven issues for $100. This makes a perfect—or at least defensible—gift for any discerning comedy lovers on your list. Supplies are dwindling, and these are so rare they are practically investment-grade (”humor magazines like this HAVE gone up in value!”). So consider it.

A reader asks, “Mike, what do you think of AI? Specifically in regards humor writing and cartoons, and parody?”—Three Legs

I assume you are referring to the common AI mistake, Three Legs, and not the excellent Paul McCartney song. Any of you who have not listened to RAM lately, go do so now. It is by far my favorite LP by a solo Beatle, and outdistances other Macca-stuff like Band on the Run by a mile. BotR celebrated its 50th birthday this week, and Denny Laine got so excited he died. If you gotta go, Denny, you better go now.

Before I answer your question, TL, I want to do something I’ve never read in an advice column; I want to cop to a little depression. I get it during the holidays, and being middle-aged doesn’t help. I’m missing some old friends, and pre-grieving some sick ones. The Boomers I know, and Boomer culture—from music and comedy to art and politics—has really been the joy of my life, and I don’t look forward to living in a world where people who grew up loving John Lennon and MLK have been replaced by people who idolize creeps like Steve Jobs and Ronald Reagan. Plus, nobody will get my deep-cut jokes about stuff like the Profumo Affair or The Diggers or The Cockettes or Max “Dr. Feelgood” Jacobsen or Fellini. I’m going to see La Dolce Vita at the Aero tonight, and I hope that will cheer me up; it’s one of my favorites.

So—given my general glumness—you’ll be unsurprised to learn that I believe AI is going to entirely take over corporate-owned media. It is corporate media’s Holy Grail, and since we have no stomach to stop such things, it will grow and spread immediately and relentlessly. “Siri, write me 750 mildly amusing words interspersed with Beatle references.”

I think the best human writers and artists can hope for is to create original IP that is then bought from them and expanded infinitely by corporate-owned AI. But I think that will only really be an option for the first few people, because AI-driven expansions of whatever the corporations own are going to be immediate. It will fill the bucket past full. We’re already at full. This week I unsubscribed from about 20 Substacks because—forgive me—I just wasn’t reading them. Writers may need to write, but do the rest of us really need more to read? And what is writing without being read? It is a question worthy of a Zen koan.

There is a finite amount of attention, and every new thing is competing with all the other media that came before. There was a finitude to the pre-streaming media ecology that essentially forced support for new creation, and artificially expanded the scale of success for new things. SNL became a cultural phenomenon because of scarcity; if SNL’s audience in 1975 could immediately watch the best comedy of the previous 50 years, plus Lemmings and The Committee and every Carlin routine on YouTube, and stream the previous five years’ of Pryor small-club gigs via RichardPryor.com, and get new Robert Klein material sent to them via email for $9.99/year at Icantstopmyleg.com…SNL would not have achieved escape velocity. AI isn’t solving a reader-side problem of not enough content; it’s answering the corporate prayer of creative content without creatives.

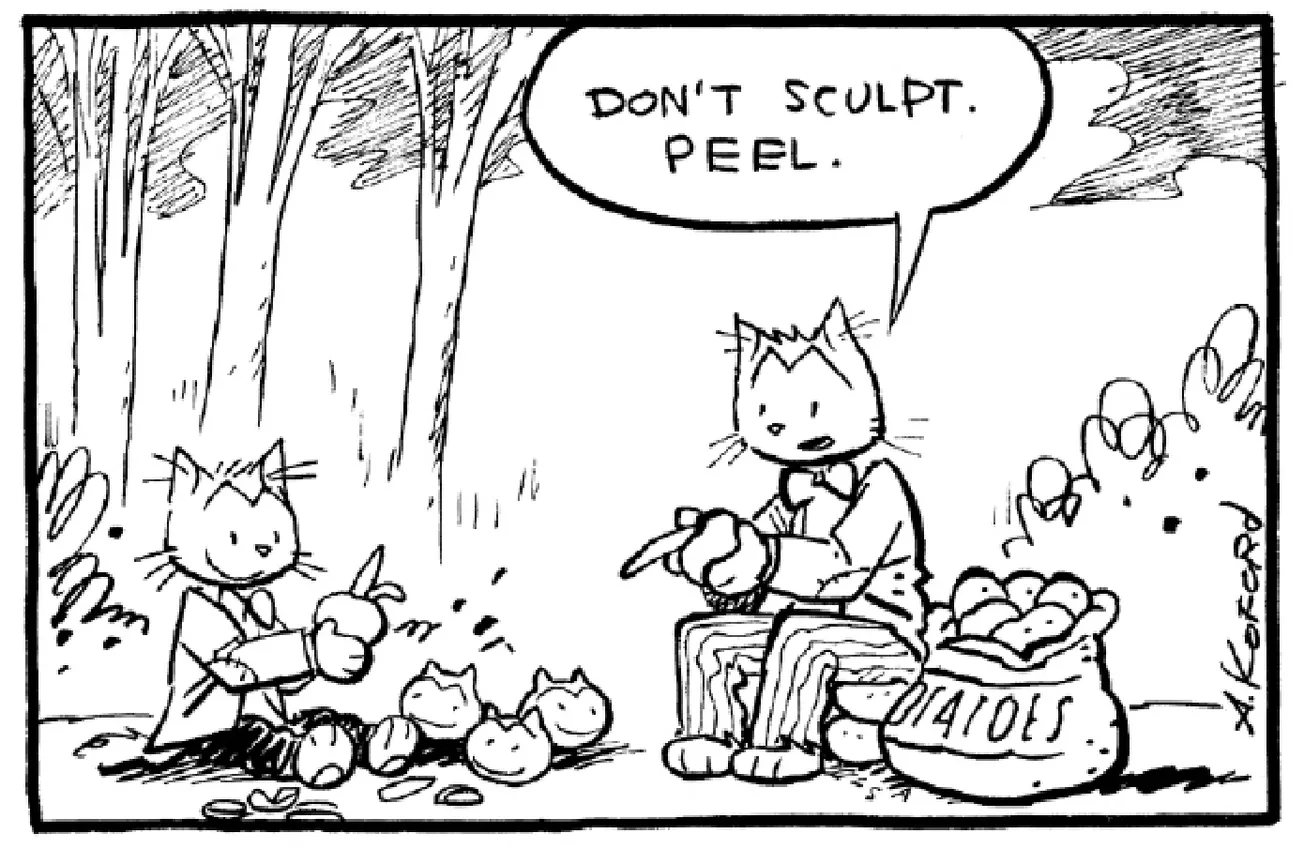

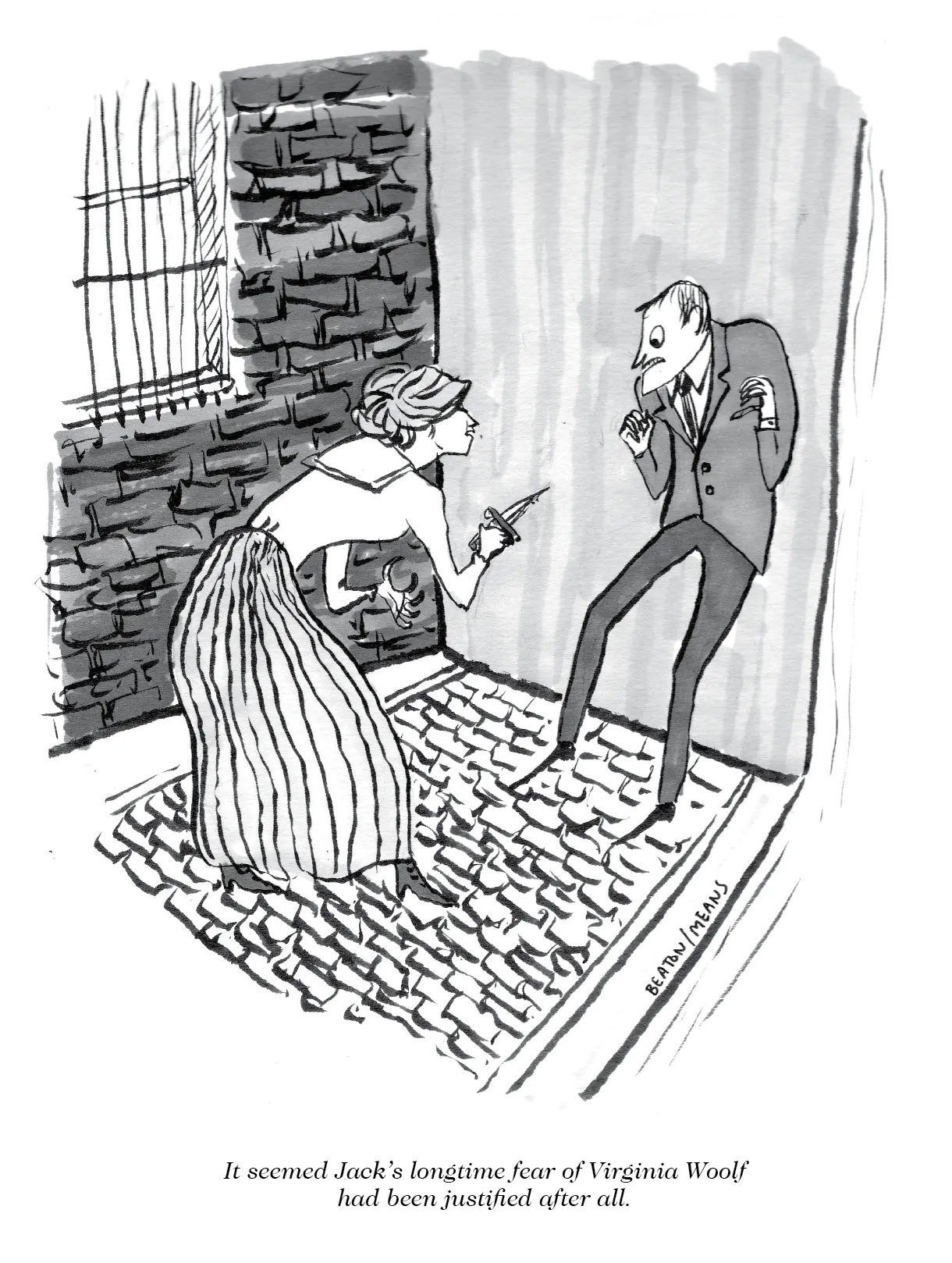

As to the stuff I know best. I think kinds of things The New Yorker publishes will go first—cartoons, and topical casuals. Earlier this year, I was in a Zoom with a person who I will not name, but who is in position to know, and whose opinion I trust; he said that within a year AI will be able to create one-panels indistinguishable from human-generated work. At that point, he said, the job of “creators” would be crafting prompts and sifting through the pile.

With “casuals”—pre-Newhouse New Yorker slang for short humor pieces—I think that goose is equally cooked. Creatively, the short humor form has ossified massively over the last 20 years. This is arguably a reader-side change; readers have wanted simpler and simpler premises, and less and less authorial eccentricity, as they have been forced to process more and more words per day. Benchley’s genius is how he felt utterly distinct from the content around him in, say, Vanity Fair circa 1919; today’s humorists all kinda sound the same, because that’s all overstimulated readers can process easily. Just as parody has ossified into one style—The Onion’s—short humor has turned from an individualistic artistic form into today’s item of the zeitgeist being put through The Comedy Machine. David Sedaris is the last person whom I can say for sure achieved durable fame via old-fashioned casual writing—a truly distinct voice, talking about topics only he would cover, writing at variable length, and achieving an extremely strong personal connection with the reader.

Corporations hate this. A personal connection with the reader—name-brand power— is the only thing that gives writers leverage in contract negotiations. I never knew how much they hated it until Barry Trotter hit #2 on the London Times bestseller list. My publisher’s response wasn’t to sign me to a long-term deal, but to flood the market with basically every copycat parody they could buy. These books were half as good—they weren’t written by comedy writers—but the publisher found that if they packaged them the same, and promoted them hard enough, they could use the positive experience that I (with Barry T.) and Doug and Henry (with Bored of the Rings) had given millions of readers, into enough “fooled you!” sales to have a couple more nice quarters.

Though this killed the market for my work, this was a win-win for them; they could squeeze maximum money out of the “fad”, and also prevent me (and anyone else) from ever having them over a barrel. And parody isn’t something you can own; In Barry, demonstrated a lot of tricks, which I’d developed over decades of reading, writing and interacting with audiences, and those tricks were dutifully incorporated into competing works. AI is like the editor’s buddy looking to make a quick £5000, only better—it’s basically free, and fast, and gives all control to the publishing company.

I do not see any reason this will not happen, especially with something as technique-based as parody. If AI cannot generate Onion-style comedy now, it will by next Christmas. Ditto, the voicey, post-Gawker humor stylings that dominate Substack.

So what’s the good news? Is there any good news? Well, AI could potentially create a golden era for editors and editing, and as someone who loves those largely discarded arts, that’s a bit exciting. I am just about to launch a very strange and wonderful business with a friend that uses the very uncanniness of AI to its advantage. Current AI, when piled on top of itself sufficiently, can create a distinctive and oddly beautiful environment.

But the problem with AI and comedy, or really any kind of creative expression, isn’t really with AI. It’s with a culture that once worshipped artists, and now worships oligarchic monsters with no real longings left but a fierce desire to be released from the frail bonds of human decency. If you want to know why I’m depressed, it’s because I’ve watched the societal decay from Sgt. Pepper to Cybertruck. And endured all the gaslighting—every step of the way, technophiles and the corporations profiting from them have trumpeted it all as innovation, ease, some unlocking of the human spirit. When what it seems to do is empower the worst people, and once released, there’s no going back. Sorry to all the cyber-philosophers I used to read in Mondo 2000; the natural endpoint of social media isn’t the world’s people coming together in peace and harmony, but the opposite. We know this now, and apparently all we can do is get into March Madness and buy a few back issues.

Al will only damage us to the degree that we do not value human beings, and privilege and cherish the art they make. Does our society value human beings? Do we protect artists, and cherish the art they make? You do the math.

But that could just be the holiday depression talking. RAM’s almost over; after that I’m going to go listen to Sgt. Pepper.

Every so often, The American Bystander’s Editor & Publisher Michael Gerber answers questions from readers just like you. To add your question to the pile, email publisher@americanbystander.org and put “Question” in the subject line.