A reader writes:

“You're probably familiar with the law of the Hammer. A/k/a, "when all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail." Suppose you were only allowed one solution for every future problem in your life. One hammer to get you through every subsequent problem that you will face before shuffling off this mortal coil. What would you choose?”

This is different than the Law of Mike Hammer, which is “sock a dude, drink a boilermaker, kiss a floozy, and drive off into the night,” which is admittedly antisocial but has greater and greater appeal as I get older (and any possible jail time perforce decreases).

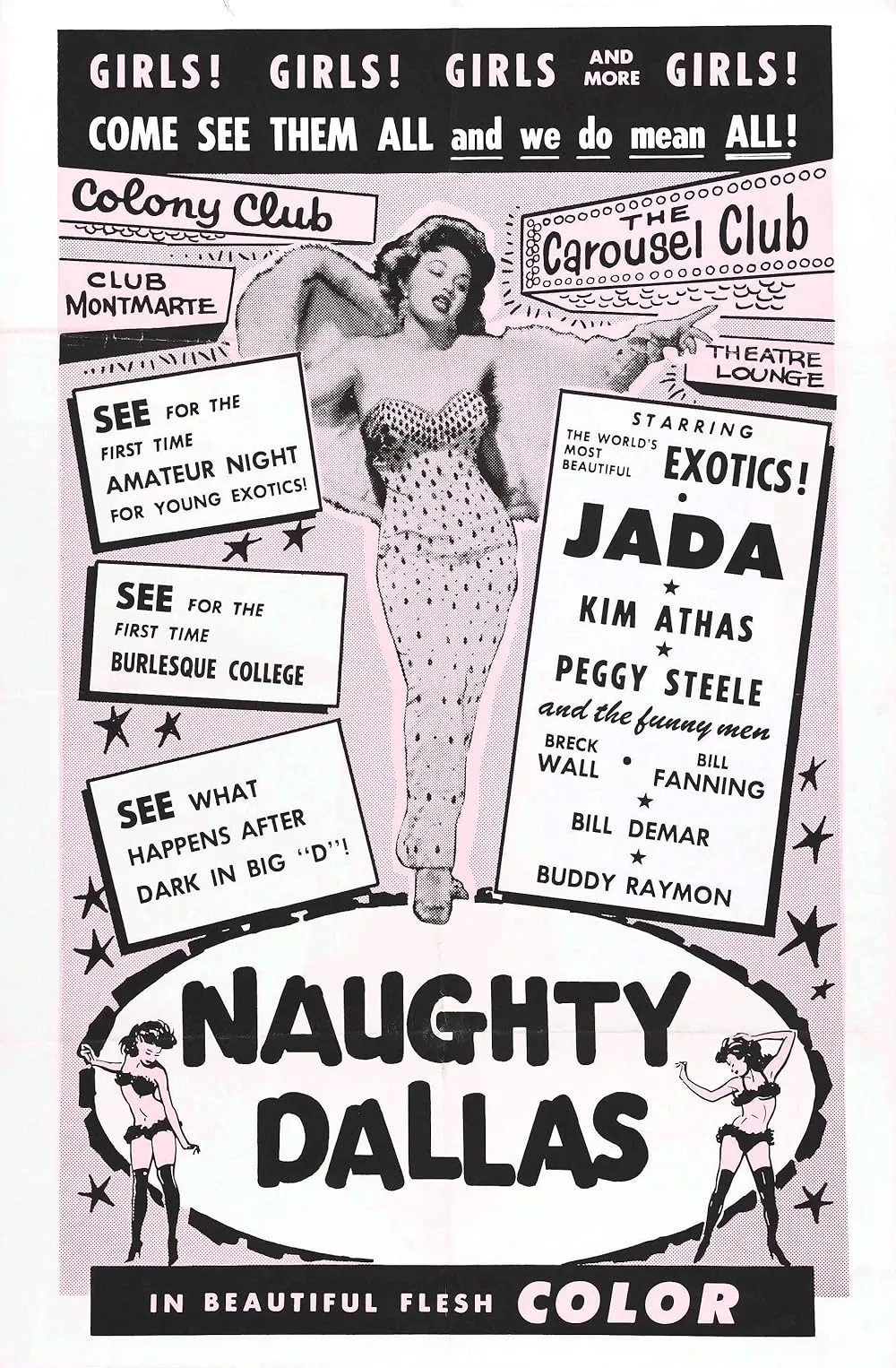

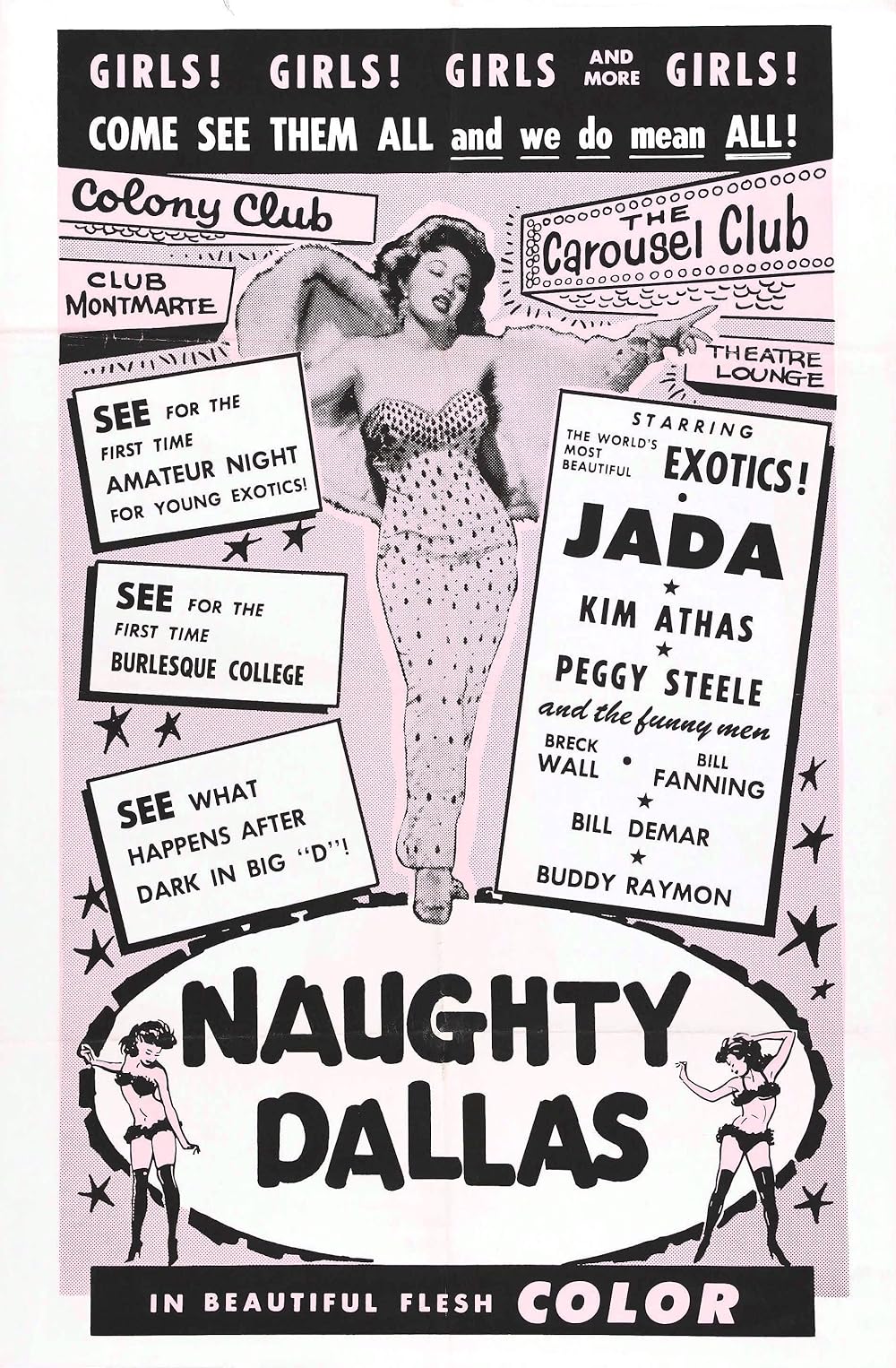

By the way, there aren’t floozies anymore, and the world is poorer for it. The night after the Beatles played Sullivan, the worldwide manufacture and distribution of floozies ceased, and the world’s stock began dwindling. The last time you see them, really, is in Jack Ruby’s Carousel Club in Dallas in 1963. Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies were floozies, too. But I’m pro-floozy, of any and all sex. Bring back floozies!

Anyway, I’ve given this a bit of thought, Reader, and my answer is sincere but will likely feel quite unsatisfying: were I restricted to one, just one hammer, I would elect to stay quiet, observe, and react as little as possible. Do as little as possible. Possibly smoke a Cuban cigar, but that’s it. (Bolivar Belicoso Finos, thank you for asking.)

Now you’re probably thinking, “Do nothing? This guy has studied a lot of Buddhism. Perhaps too much.” And you would be right. But I’ve also observed that most of my problems in life have come from what could be called “scheming.” I want a certain outcome, then formulate a plan—a scheme, really; a heist—to achieve that outcome. It seldom works, and even when it does, it takes years instead of weeks and causes all sorts of regrettable boring mayhem along the way.

Old people aren’t particularly wise; some are, in fact, dumber than they were when they were young. I know I am—a lot of these days, mentally, I’m looking up at sub-normal. But older people do less, and so bad things happen to them less, and what they do set into motion is more successful. They’re not running a million schemes, a million heists at once.

To me, the people who epitomize scheming as a way of life are mobsters. My neighbors were friends with Henry Hill, the mobster made famous by Goodfellas. He would come over to their apartment for dinner—my neighbor is a very good cook—and we would nod and smile at each other in the hall. “Hello sir, they tell me you write humor”/“Hello sir, I know you have killed people”—all very cordial. I talked to Henry in the elevator a couple of times, and he seemed pleasant; he had been well-fed and well-liquored, and seemed to be digesting without issue. I would submit this was because his scheming days were over. Or, largely over. Or, at least he wasn’t robbing actual planes at the actual airport.

I, on the other hand, a more honest man by most measures, couldn’t eat a cracker without feeling like I was going to throw up. I think it was because I was always scheming. “If I do this, then I’ll sell another book” or “If I talk to that guy, maybe I’ll be able to start a humor magazine.” Meanwhile the fellow next to me—who was world-famous for actually murdering gents—was breaking his chicken cacciatore down into useable nutrients as effortlessly as St. Francis.

Scheming, it’s no good for ya.

Even when your schemes are successful—when they get you what you aimed for—they seem to leave a troublesome residue. I look to my right and see the boxes of Bystanders in my living room. Residue. The stuff that slows life down and makes it sticky.

You wouldn’t know it from walking around, but my quiet little neighborhood by the sea seems to be loaded with mobsters, and I’m not just saying that because there are a lot of saggy-scrotumed old Russian dudes who accost me in the locker room at the YMCA. The other mobster who lived near me was Whitey Bulger; he was finally smoked out exactly four blocks away, over on Second Street. It’s a very pretty quiet street, one of my favorites, with a canopy of big ficuses (fici?) that I love to bike under. I don’t care what you think of Boston, Second Street is a step up, especially between October and May. So by the standards of his business—and perhaps of any business—the notorious Mr. Bulger had been a success. His scheming had worked. But all that “success” led to him holed up in an apartment with guns and money in the walls. Not a place I want to be.

So, kind Reader, my Hammer is doing less, and observing more. Trying to do things for the simple, immediate enjoyment of them, not as part of a scheme. Doing less is not natural for me, I have to really work at it, but so far it seems to be working all right. As a Hammer, it would cause the least agita, and that’s a lot.

This was a tough question. I’ll be interested to hear other opinions in the comments—what would your Hammer be?

Every Friday, in between contemplating his upcoming eternity in torment, The American Bystander’s Editor & Publisher Michael Gerber answers questions from readers just like you. To add your question to the pile, email publisher@americanbystander.org and put “Question” in the subject line.