Like meeting your future spouse or feeling that first kidney stone, I remember exactly where I was when I encountered Donald Watson’s drawings: It was approximately 4:57 on a sweltering July Friday in 1991. I was hunkered down in the dusty-smelling air conditioning of The Yale Club of New York, flipping through pages of my old college humor magazine as fast as I could. Having graduated six weeks earlier, I was reeling—the pungent reality of pre-Giuliani Manhattan (and the even more pungent publishing business contained therein) was exploding all around me, like bags of uncollected garbage dropped from a great height.

Seeing my disorientation and taking pity, a generous alumnus had arranged a meeting with a friendly editor at Knopf. We hoped to get a little dough for the old college rag, and a little money into my pocket, with a collection of cartoons from the first 100 years of The Yale Record.

This wasn’t purely gross Ivy nepotism—The Record has been a farm team for The New Yorker since before there was a New Yorker, beginning with Curtis Arnoux Peters ’23 (known to you as “Peter Arno”) and continuing with…yours truly, eventually. But that was nearly a decade away; back in July 1991, I had to finish that proposal, ace Monday’s meeting, and set off on the extravagantly celebrated, preposterously lucrative career my family had paid for.

It wasn’t going well. After struggling with the proposal for a week, I’d spent another week here in the library going through issues, and had an inch-high sheaf of xeroxes to show for it. But something was undeniably missing—I needed a cartoon both in- and outside its time; something simple, but profound; funny, yet more than just funny.

In other words, a cartoon that didn’t exist. And the library was closing.

Flipping, glancing down the page, glancing at the clock, grabbing another volume. Arno, Osborn, Stevenson, Grossman, Hamilton, Trudeau, the pages and decades flew by. All of them were amply represented in my xeroxes—but I was missing a topper. Or was it me? God, my mind was Wheatena. Would this project ever be done? And if I couldn’t finish it, what would I do then? What would that augur for the years ahead? How much more pungency could one man take?

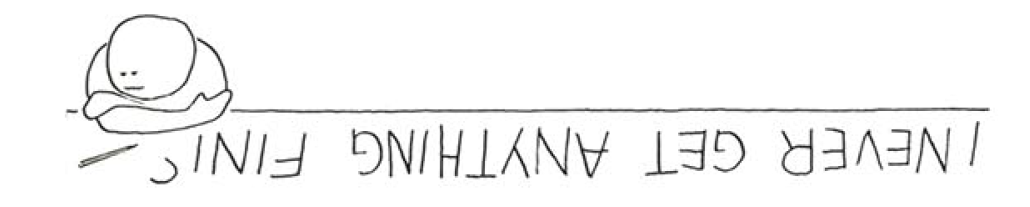

Then I saw it: a drawing in a long horizontal strip, where a man who looked like he was made of soft dough sat glumly, unable to finish the following sentence: “I NEVER GET ANYTHING FINIS”

Now this was an artist in touch with the human condition.

Down the hall, I heard the jingle of keys—Louise the librarian was locking her office, where the xerox machine was. I jumped up and ran, holding the heavy book. “Louise! Don’t lock up yet!”

“Michael, I have to go,” she said. “I have a long commute.”

“I know, I know.” She was a lovely lady; we’d spent the last two weeks together, and I’d told her about my big meeting. “I just found something really great.”

“Come back Monday.”

“My meeting’s Monday at the crack of dawn. [That’s publishing slang for 10:00 a.m.] C’mon, Louise, please? I’ll be two minutes, promise.”

She paused, and I pounced. “Look at this one.” I held the book open to Don’s cartoon. Louise laughed…and unlocked the door.

Thirty-odd years after he drew it, Don Watson’s magic had struck again.

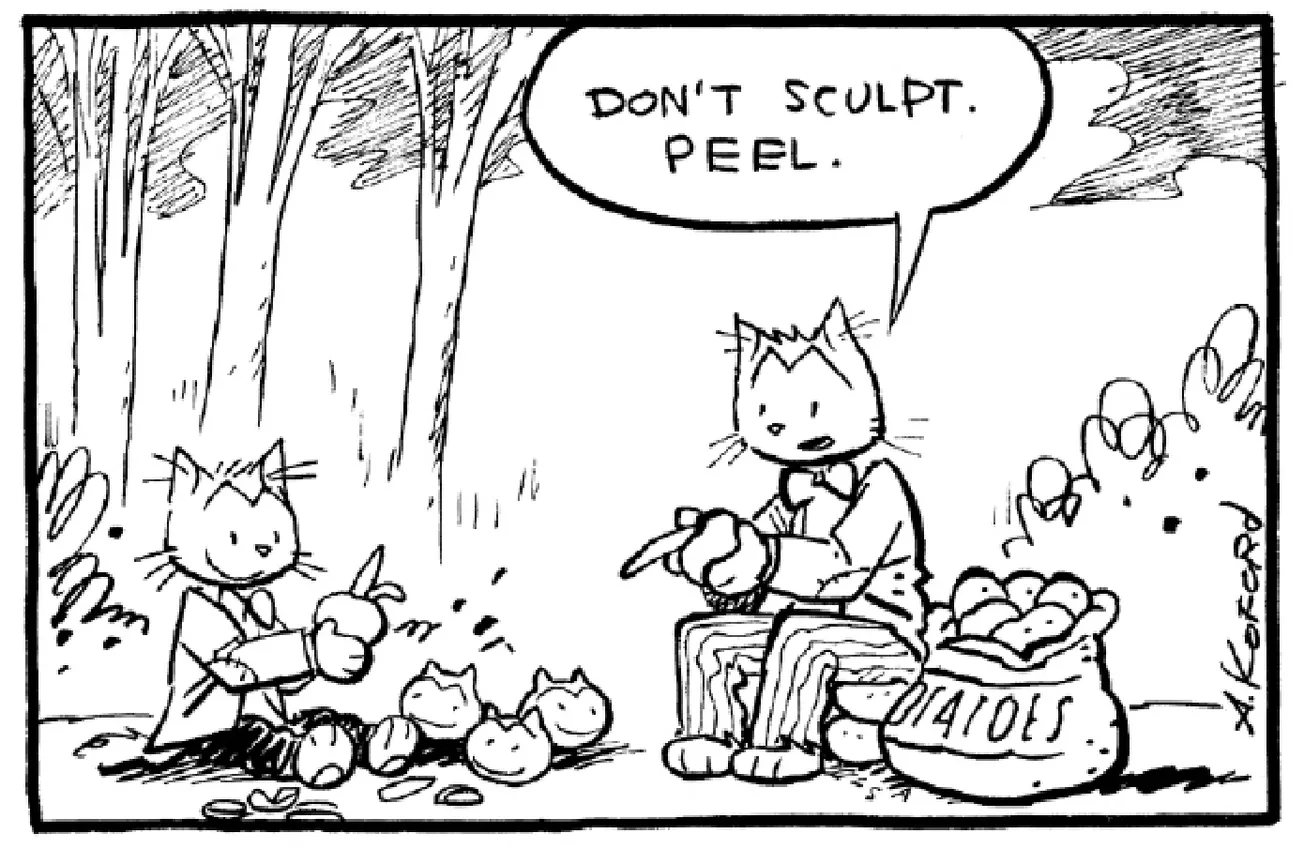

Today, thirty-odd years after that, I have the pleasure of running Don’s magic in my magazine, The American Bystander. Don and I have become friends, and I remain utterly gobsmacked at his ability to arrange just a few lines and a splash of watercolor into the entire human experience—not to mention that of storks, porcupines, and Godzilla. (And that’s not even including the pancakes.) Since I now know the man, I see the mind behind those cartoons. It is a unique mind, a remarkable mind, one that lightens—and slyly ennobles—all it examines.

Don would never allow me to flatter him like that in public, but since it’s just you and me here…

Immediately after college, Don turned down an offer to work at Esquire, opting instead for a career in architecture. For many years, he busied himself with such trifles as penning the first textbook on solar architecture (a million seller), or trotting around doing projects designed to cool an Earth with the first beads of sweat already appearing on her upper lip. Sometimes, for his own amusement or a friend’s, he would draw a cartoon. We’ve reprinted some of these sketchbook pages in The Bystander, and one has even made our cover, an honor reserved for the greatest illustrators of our era. It fits, as Don fits.

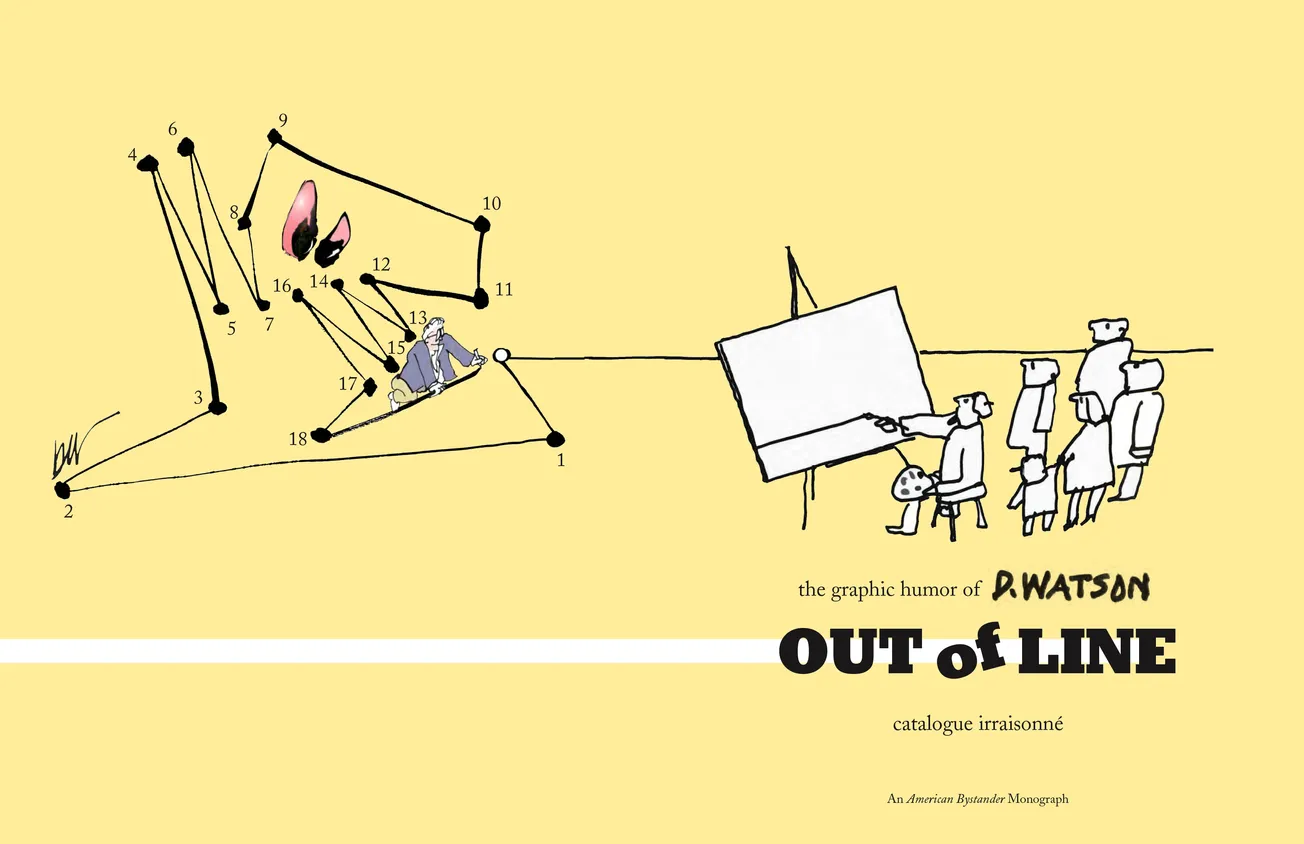

Don has been part of Bystander’s all-star team since the beginning, and he epitomizes what we are trying to do. So when he seemed amenable to our publishing a collection—a catalog irraisonné, as he wittily calls it—I leapt at the chance. Now many others will get to spend time in Don’s world. What is Watson-world? Gentle, sophisticated, silly, occasionally antic, with more grace than the viewer has any right to expect. It’s a nice place to visit, and you may want to live there.

Thank God Don didn’t take that job at Esquire. Some might quibble, but Sixties Esquire is generally considered to be the best American magazine ever. Great writers, great editors discussing an era where amazing, incredible, horrific things happened, trends came and went, personalities were birthed or seen off, at precisely the right pace for a monthly pile of ink on paper. But all that having been said, Esquire’s cartoons are weak. Think Playboy, only inhibited, The New Yorker, but less certain of who’s reading. Now if Don Watson, young and tall and full of talent, had been on staff? The whole magazine would’ve gone down in flames.

Let me explain: I believe all human endeavors are gifted by our Creator with a flaw, not because He is a jerk, but because He wants us all to keep trying. And I think if D. Watson had accepted that job offer in 1959, some fatal flaw—something really terrible—would’ve had to happen to the entire company, the entire building, the entire city block, just to keep the Universe in balance. Don can only appear in Bystander because it is full of my mistakes. Sure, it seems like I’m overworked and undertalented, but since it’s just you and me here: I do it on purpose to counterbalance Watson.

Because Don paused for a few decades, his stuff is a unique treasure. Almost as if he planned it, he missed the sorry decay of American print, its replacement first by television then by the internet. The bones of Don’s work come from that mid-century high point of our culture, when one-panel cartoons really mattered. And because he is always utterly himself, his work continues to shine. It appealed to people in 1959, and in 1991, and today. And thirty-odd years from now, and thirty-odd after that…

Whatever happened to the book proposal? it went down in flames—and if I’d been smart, that’s the moment I would’ve pivoted to something truly useful. Not architecture, but maybe one of the soft sciences, like tarot-reading.

I still remember the young editor handing me back the sheaf of cartoons. “These aren’t very funny, are they?” he said. “Oh, except for this one.” He pointed to Don’s cartoon. “My girlfriend xeroxed it and put it on our fridge.”

I know lots of cartoonists, the best ones in the world, but I don’t know anyone else quite like Donald Watson. He is a genius that nearly got away, and if all The American Bystander ever did was give him a stage and a spur, it would justify all my mistakes.

Enjoy this collection; it is an honor to present it to you.

—M.G.

Santa Monica, CA

June 2023

Out of Line: The Graphic Humor of D. Watson will be published this fall. Don’t worry, we’ll make sure you have a chance to buy it. :-)