The movie director William Friedkin died this week, at the age of 87. I had the same reaction I always have. First, I do some quick math. “87-54=33. Thirty-three years ago, I was 21. That feels like a long time ago. Thank God, I have a long time before I’m 87.”

Then I think, “Dead? I didn’t even know he was sick!” as if there’s some newsletter I forgot to read. Whenever someone famous dies, it feels like I’ve fucked up. Like I hadn’t spent enough time with him, and now he’s gone. “I never even told him I liked The French Connection!”

I feel this way because I have plenty of older friends whom I should be spending time with, and this increasingly makes everything else I do—including writing, especially writing—feel like a waste of time. It’s not that I have fewer jokes in my head these days, it’s that there are all these important things I have to say to people first.

Death is perfectly natural, and what’s more it has to happen, simply to save space. But I’m really beginning to resent it; continuing to live feels like living in an apartment where someone sneaks in every night and steals something. There’s still plenty of stuff—for now—but I’m starting to see the holes. It’s disconcerting, a little eerie. It can’t go on like this. Someday I’m going to reach for something and…it won’t be there. It’s starting to feel personal. I simply haven’t planned for living in a world without William Friedkin in it. Or Paul Reubens. Or Robbie Robertson. Or Tony Bennett. Or Conrad Dobler.

Surely you remember Conrad Dobler? Offensive guard on the 1975 St. Louis Football Cardinals? Member of perhaps the best o-line in history and, reputedly, the meanest man in professional football?

Next to, of course, Jim Brown. Also dead.

Brown’s death brings up the uncomfortable matter of legacy, of toting up some score. As a society we’re poised between unquestioning worship of celebrities, and implacable rage at them. Don’t ask me how to feel about Jim Brown; he was an amazing football player, who was also an abuser. To say I admired him is overstating it—it’s more I acknowledged his largeness. Like George S. Patton or Picasso (or it must be said, O.J.), Jim Brown struck me as a person whose precise accomplishments suggested a big dark side. I get the same vibe from John Lennon, whose misdeeds we largely seem to know, and Andy Warhol, whose misdeeds we largely seem to not.

Do you have any doubt that Warhol has skeletons? That he left a trail of broken promises, busted people? I don’t. But neither do I blame him. The more people that die around me, the less I feel qualified to judge, simply because what I know seems so partial. I knew Friedkin as a great filmmaker and a fascinating guy to listen to from my seat in the ‘way back of The Aero. So, he was OK in my book. But when he died, my friend said, “I used to work with Billy Friedkin. Awful, awful man. Sadist. I saw him make grown men cry. And take pleasure in it.”

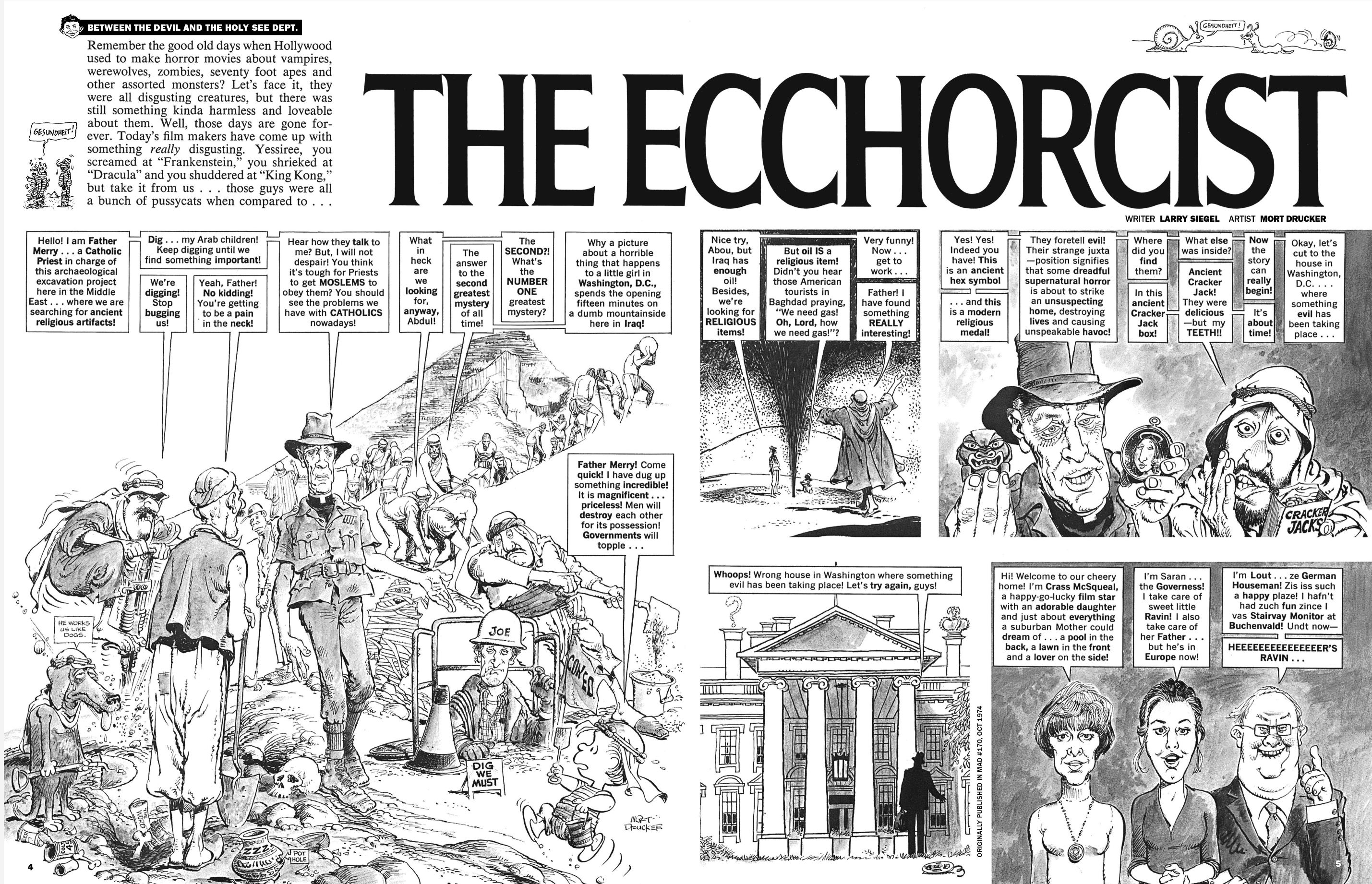

What is anybody’s legacy? It’s all tangled up in time and place and random chance. I mean, for Christ’s sake, the MAD Magazine parody of Friedkin’s The Exorcist is one of my first comedy memories. It certainly exerted some tiny influence on my eventual choice of career. How could it not, look at that spread! Has there ever been a finer illustrator than Mort Drucker?

The hullabaloo over that movie, which came out when I was four, was one of my first memories, period; my family is Catholic, and family lore says that our parish had some connection to the actual Exorcist. (Amazingly, this turns out to be true.) My younger sister Katie—by far the most spiritual of us, the one who sees ghosts, has dreams, and still goes to church—was so flipped out by The Exorcist that…well, a lot of things happened.

For years, whenever Mom would take her to the local video store she would beg to be allowed to see The Exorcist. Remembering the absolute psychic carnage inflicted upon me by JAWS, my mother said no. But Katie was persistent, and one Saturday night when she was about 15, Mom relented. VHS tape in hand, Katie invited a bunch of pals from Trinity over for a sleepover. They watched the movie—or, I think, only part of it. What I know for sure is that Katie got so freaked out she wouldn’t even speak of it. For years. For years, if you wanted my sister Katie to run out of the room, you mentioned The Exorcist.

The strange thing is, she didn’t return the movie, either. We had one of those old-fashioned answering machines, the ones where you’d push PLAY, and the message would be broadcast for everyone to hear. Every time I’d come home from New York, I’d hear the same weary voice: “Hi, this is Rick from MTL on North Ave, calling about your rental of The Exorcist. Please call us back. If you don’t return it, you’ll be charged the $75 restocking fee.”

“Katie,” my dad would ask, “where’s that goddamn tape?” And Katie would leave the room.

Later, my brother Jack told me what had happened: the group of girls had actually set the movie on fire, then buried it, like some sort of evil relic or undead creature, in the back yard of our old house at 250 Forest Avenue. If you live near there, go dig it up. I want to see if that family lore is true, too.

Friedkin wasn’t the most entertaining interview I ever saw at The Aero—that would probably be Harlan Ellison, who somehow made an entire career out of DGAF, a unique achievement in the history of Los Angeles. Nor was Friedkin’s appearance the most memorable; that would unquestionably be David Carradine, whose hour on the stage involved off-key singing, hitting an audience member with a microphone, and—you know that moment where you think, “There’s gonna be a fistfight”? Imagine that lasting 45 minutes. (Safe in the back, my mouth hung open so long my tongue actually dried out.)

But Friedkin was always great, not just because he made a movie I frequently return to—The French Connection—but because when you looked out at him, dropping truth bombs from a cheap director’s chair, you saw a fellow fan.

Old movies are one of my life’s passions, and I suddenly realize why: they, more than any other art, defeat death. Unlike books or music, they move, they show form; unlike TV, they’re BIG. When you’re watching Chimes at Midnight or Citizen Kane, there is no doubt you’re in the presence of Orson Welles. From the very first frame of 8 1/2—Friedkin’s favorite, and probably mine, too—one receives distilled essence of Fellini. Taxi Driver does the same for Scorsese, JFK Oliver Stone, Apocalypse Now Coppola. For two hours in the dark, beneath a flickering beam, you are in the presence of the artist; they live again. This is indeed heavy magic, performed by the greatest of wizards; that’s why projectionists have such a powerful union.

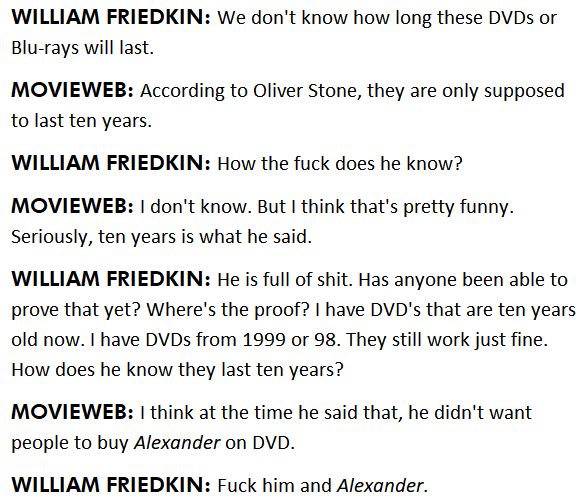

A snippet was going around Twitter this week:

You tell ‘em, Billy. The magic of old movies is more powerful than that. Groups of young Catholic girls will be burning and burying copies of The Exorcist ten, twenty, a hundred years from now. And that’s a great thing, an accomplishment to be toted up. So fuck him and Alexander.