As someone with a body who’s BEST BY date was—let’s be generous and say 1977—I feel my mortality a lot. How I deal with it is teaching. Is this better than philandering or hairplugs? That may not be a fair question. I don’t think we choose our natures; I think we’re just along for the ride.

For 25 years, I taught Yale students comedy writing, magazine design and publishing. They seemed to enjoy it, and it was one of the most fruitful experiences of my life. Now, I’ve begun coaching older people, and that feels mighty fruity as well.

Older people often feel there’s no place for them in mainstream comedy. They are right.

The first time I felt over the hill, I was all of 26. I was living in New York and submitting to all the big places, with some success. I turned on Comedy Central and saw this special. Mitch Hedberg was a fine standup…but he was no Bill Hicks. Hicks I felt a kinship with; we were both precocious comedy nerds living in the shadow of the Sixties. We’d read the same stuff, had the same obsessions.

Now, Hicks was dead. Now, the hot comic was “Steven Wright plus heroin.” I couldn’t go there; I didn’t want to go there. I felt used, jilted; something I’d really loved and given my whole heart to, comedy, had moved on—and I was just 26. I suddenly saw myself as the old guy at the frat party. Forty years of Dave Berg making jokes about the Pill.

There was nothing to do but double down; whatever I was, I was going to be it so hard. Not just write parodies of The Wall Street Journal, do it for twenty pages. Not just write a chapter of a parody of Harry Potter, but a whole book, then self-publish it, daring them to sue me. Not just do a print humor magazine, do 24 issues (and counting). My dander was up, and it has remained up. Comedy can’t just be an endless chasing of a new platform, the 12-24 demographic, “the discourse.” It has to be much bigger than all those things, so it can stand outside them and satirize those things, too.

The only way I know to get that big is to have experiences. And then to talk about yourself, honestly, with all charm and no harm. Older people can actually do this better, because they’ve got more life to draw upon. That’s what I try to teach, because I think it’s what readers really want. It’s all any writer really has to give.

• • •

When I started in the business 34 years ago—I date my professional career to the first time I got screwed, when a Senior with a book deal reprinted my work in his novel without paying me—basic comedy instruction was rare. I remember there was a book by Gene Perret that everyone read, but he was a writer for The Carol Burnett Show for God’s sake. Things started getting better near the end of my time in New York, when the UCB brought Chicago-style improv to town. But I’ve never been super-interested in teaching mechanics; comedy writing came naturally to me—by ear, by eye. Just look; just listen. I assume the passion, which leads to the skill; what I want to teach is the magic.

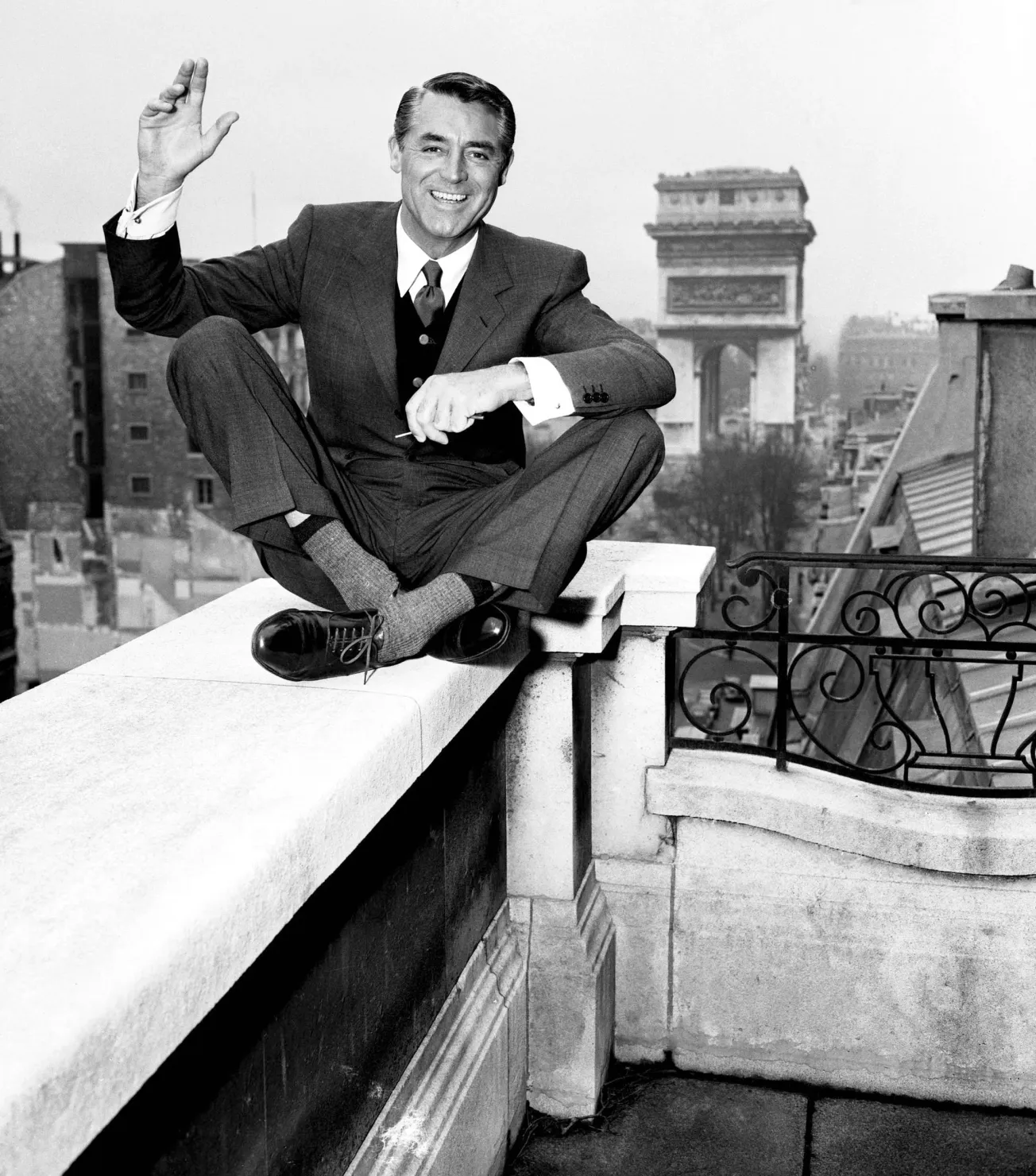

Today, there are many great places to learn the nuts and bolts—Bystander Scott Dikkers’ How To Write Funny for example. And any half-decent improv school can teach you how to write Onion-style parody, or a modern New Yorker casual. These are highly standardized forms. Working with me is different. Think of it like having lunch with a legendary cat burglar at the Hotel Metropole in Monte Carlo. He says he’s retired but, theoretically, just this once, since you’re asking, if one were to try to make money with a parody of White Lotus, one might…

Comedy writers should, in my opinion, be as rare as cat burglars. An exotic, glamorous, cunning profession practiced by few. Maybe not even me; I have Marx’s Disease—like Groucho, I often wish I’d been a doctor. It was Orgo that stopped me; I still remember pre-med friends staggering home, white-faced and spent. Also, I can’t stand the sight of blood, and if I’m around crazy people I start to think, “Maybe I’M the crazy one.” So I’d need to be a special kind of doctor, someone that makes people feel better without chemistry or surgery or Thorazine.

In other words, a comedy writer.

I was recently speaking to a current client, a very thoughtful and funny gent from Chicagoland. Whatever we begin by talking about, we always end up in the same place: “Share yourself with the reader. Really say how you feel. What’s happened to you. Who you really are.”

I’ll leave the Louis C.K. jokes to you, but sincere self-exposure is surprisingly rare advice in the comedy writing world. A lot of the classic writers that contemporary comedy people love the most, don’t really do this. On the page, Robert Benchley was a bumbler befuddled by rotary phones. In life—at least according to Tallulah Bankhead, who did have some basis for comparison—Bob B. was “a master cocksman.” Which humor piece would you like to read?

And then there’s Woody Allen, who used those same tropes forged in the 1920s to create a über-likeable (and sexually harmless) nebbish persona which charmed millions. I think that’s one reason why the Soon-Yi scandal has stuck; people resent how totally Woody had us fooled.

For about five minutes there was a vogue for shooting straight—not coincidentally, the period in the mid-70s when I personally woke up, and Bill Hicks did, too. Is there any doubt Michael O’Donoghue was exactly the person he seemed to be? Or John Belushi? Or Richard Pryor?

Then irony came into vogue, and not by accident. After 1980, comedy writers began to find themselves in a bind: Since the Sixties, a joke had to feel at least a little (and ideally a lot) outrageous for audiences to find it funny. But there was less and less cultural unanimity on anything, and so it was harder than ever to predict what a given reader would find offensive. Irony was the perfect solution. You could be outrageous, gathering up all the people who needed that to activate their laugh reflex; then if someone took offense, you could say you were just being ironic. (You can still see this approach today in a lot of right-wing “humor.”)

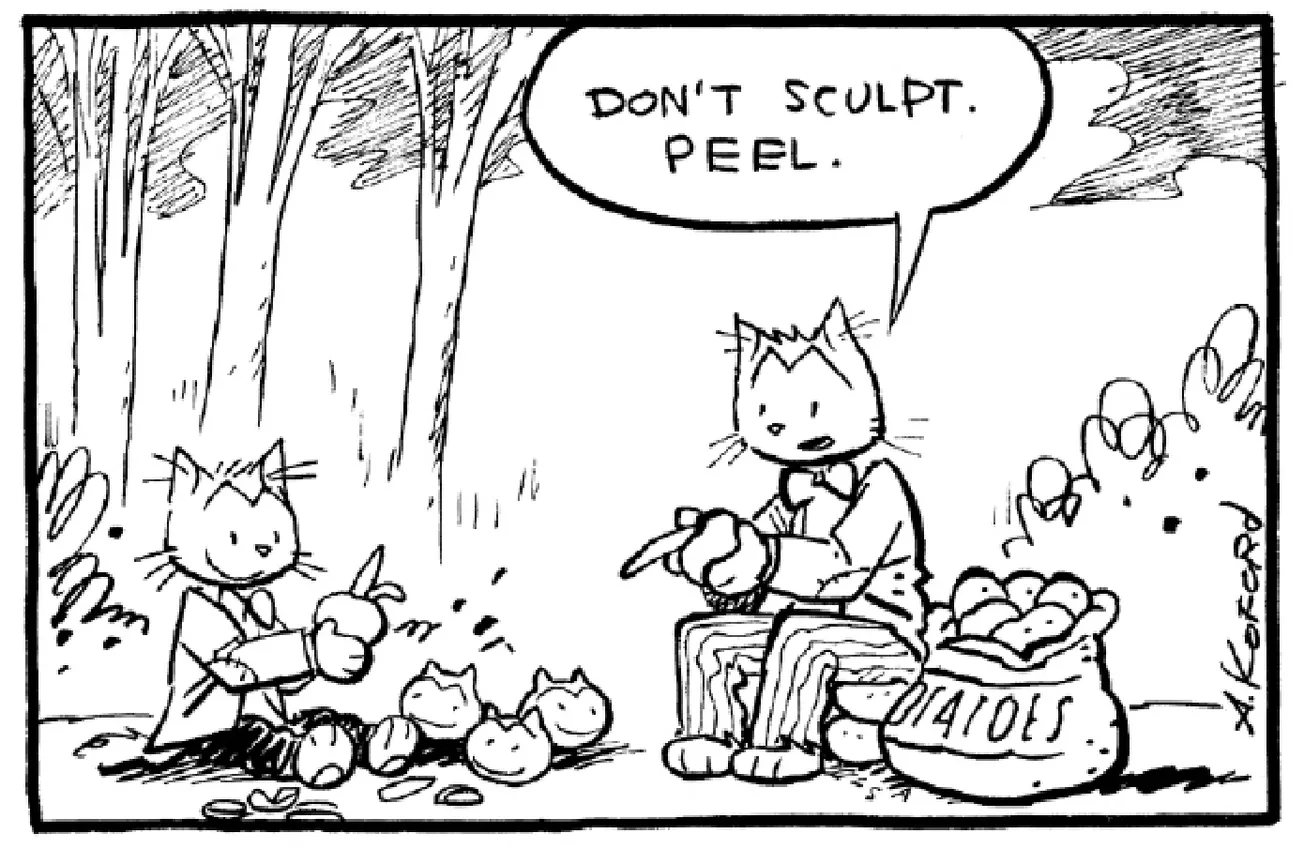

Less cynical writers tried another tack—in their hands, smart comedy became fantastical, theoretical, almost like fairy tales or commedia dell’arte. Stock characters provided the shared expectations, and pages and stages bloomed with jokes about cowboys and ninjas, pirates and robots, God and the Devil. But they too were hiding. Where the ironists hide behind cynicism, the fabulists share even less of who they are.

Then there’s The Onion, which solved the problem in perhaps the slickest way of all: it was a supernaturally sharp lampoon of everything, written by no one in particular. The geniuses at The Onion could be as wild as they pleased, because they were anonymous. The outrageousness problem was successfully solved, but at the price of any kind of fame (or power). And what they did felt weirdly impersonal, like factory workers shoveling reality into one end of the machine, and hilarious jokes being extruded out of the other.

All of these are gestures towards the same goal: comedy minus one—jokes with no creator. Readers can laugh at this stuff, but they don’t bond with the person who wrote it. That bond is the source of a writer’s power.

Laughs without writers is (not coincidentally) exactly what the big outfits want. They want the reader connected to their brand, not a writer. TNY wants the same thing SNL wants, which is the same thing the late-night shows want—bland, gently topical stuff with a bit of sexiness and a tilt towards the proper demo, stuff that any one of 1,000 people could write. 5,000. 10,000. AI.

There’s money in that, but no glory. When you’re working for them, you’re not a cat burglar, a lithe handsome scoundrel charming the jewels off the necks of blushing matrons, harming no one but the insurance company. You’re working for the Mafia, just another of Lorne’s button men. And that’s a whole different kind of criminal.

When I teach, I’m teaching writers how to bond. How to get power. And with things like Substack, that’s more possible than ever.

• • •

As soon as I began to write, the audience started teaching me where the bodies were buried. One of my first humor columns, written Fall 1986 for the august Trapeze newspaper of Oak Park River Forest High School, was a light-hearted piece pointing out that Sesame Street was set in, well, a ghetto. A silly, Royko-esque romp, or so I thought. Who could possibly be offended by that?

Well, just across Austin Boulevard, the Eastern border of Oak Park, lies an actual ghetto—so more than a few readers came to that column with quite personal experience. I remember one of them showing up at the Trap offices after school. This young woman was accompanied by her brother, who just happened to form a significant portion of OPRF’s defensive line.

“Which one of you is Mike Gerber?” the large young man said largely.

In the finest traditions of journalism, my editor Jerry—later the best man at my wedding—ratted me out. “Him,” Jerry said, pointing.

What followed was a very uncomfortable, but not unreasonable ten minutes. I listened a lot, explained a little, and did some apologizing. They were perfectly nice. In my experience, readers are usually perfectly nice, probably because I am clearly trying to entertain them, not hurt them and call it humor.

“When I use the word ‘ghetto,’” I remember saying, “it’s totally theoretical.”

“Not if you live in one,” she replied.

I had to agree. We all shook hands, and as they left, I resolved not to make that mistake again. “From now on,” I said to myself, “no theory. Only write from your own experience.”

What could possibly go wrong?

• • •

There was a lot about my life that my fellow Huskies couldn’t relate to—or so I thought. All the drinking in my family. My desperate desire for a girlfriend. My cerebral palsy. Now I know that’s where the real gold is; were I counseling my younger self, I’d tell him to talk about nothing but that stuff, the more painful the better. But being 17, I settled for easy harmless topic like the pizza in the cafeteria, which I roundly despised.

Part of cerebral palsy’s extensive benefits package is really tight, sore muscles. So every morning, when everybody else had gym, I’d go to a little side room about the size of a squash court where Coach Weaver—the strength coach for the football team, imagine He-Man with a buzzcut—would torture me.

That is unkind. Coach Weaver was a good man, though he did have a temper. I’m sure he didn’t like watching me suffer. But suffer I did; every school day around 11 am, I would hop up onto the training table, and using his muscles and body weight, Coach Weaver would stretch out my legs.

I think Coach Weaver liked me; I liked him. We would make small talk, he and I, and sometimes he’d even crack jokes, to take my mind off the pain.

But not today. Today, he was very quiet. And rather rough.

“I read your column in the Trap,” he finally said. “About the pizza.”

“Oh yeah?” I panted, breathless from the searing in my ankles; my bastard thighs and goddamn hamstrings were next. “Did you like it?”

Coach didn’t answer. He just draped one of my legs over his shoulder and pushed. I squeezed my eyes so tight I saw blood.

“Hey Coach,” I gasped. “That’s a little much.”

Coach didn’t respond. “Doris is a friend of mine,” he said. (Doris was the lunchlady.)

“You made Doris [big push] CRY. “

“Do you think that’s [bigger push] RIGHT?”

He was pushing so hard the words came out as grunts. I grabbed the edge of the table so I didn’t fall off. “Son of a—” I couldn’t swear; Coach Weaver was really religious. “Coach, man—”

“Do you think that’s FUNNY?”

The words leapt out. “Goddamn it! You’re gonna snap my fucking hamstrings!”

Coach Weaver roughly untangled himself from my quivering legs. “Hit the showers, Gerber.” Then, as I hobbled away: “Go apologize. Today.”

Apologizing to Doris was uncomfortable, I’m sure. Somehow I didn’t even notice.

• • •

Remembering all this now, 36 years later, I frankly wonder why I kept at it. I really loved comedy, I guess. I really loved being seen and, apparently, would endure any hardship to keep doing it. I suppose that’s why I’m an okay teacher, for a cat burglar.

And it did have its good moments, too. Six months later, I was two days into my Yale career. I walked into the rotunda of Bingham Hall—because of my cerebral palsy, I’d scored a ground-floor room—and a voice called down from the third floor.

“Hey! Are you Mike Gerber?”

By this time I had a bit of aversion to this question; I looked up into the rotunda and spied a fellow Freshman named Mary Sue. I seem to recall she was from Pennsylvania.

“The Mike Gerber? From The Trapeze?”

“Yeah?” I said, hamstrings twinging.

“We used to read your column all the time. You were great.”

“Thanks Mary Sue.”

“Our guy would steal your jokes.”

“No honor among thieves.” I walked towards my door.

“You know”—Mary Sue’s voice boomed from the gloom above, it was like talking to God, if He was a girl from Pennsylvania—“you’re a lot less funny than I expected.”

“I wish you’d told me that yesterday,” I said. “I just got a humor column in The Herald.”

“Oh, well…don’t fuck it up.”

I laughed out loud. As if I could stop. Comedy writing was, like thieving for the notorious “Cat,” simply my nature. And I was just along for the ride.