TRIAL BY FIRE(WORK)

Unlike dogs and ophthalmologists, I sincerely like the Fourth of July. Some might consider the noise and hullabaloo undignified, but I’m with George Plimpton—to me, the Fourth is the preppiest of holidays. From the mayonnaise to the mortars, the bunting to the beach, the Fourth turns every Ralph Lipshitz into Ralph Lauren, at least for one day.

For a time in my thirties, I helped keep China’s economy humming via bulk purchases at Krazy Kaplan’s firework barn. Judging by the logo, Kaplan’s is Hammond, Indiana’s leading vendor of small explosives to the criminally insane.

I don’t blow stuff up anymore, but it wasn’t the danger to my eyes and digits that encouraged me to mend my ways. As I hunched behind a fallen tree, waiting for a menacing foot-tall tube called “Boom Shocka Locka” to disgorge its “twelve assorted effect balls” into the unsuspecting sky above Lake Michigan, I had a moment of satori: many of those “assorted effects” were due to heavy metals, and since Harbor County is one of my favorite places on Earth, I probably shouldn’t be filling it full of copper, strontium, vanadium, et cetera.

Nowdays, I sit out on my balcony smoking a cigar, and as the Pacific Palisades launches a bit of extra tax revenue into the firmament, I recall the happy summers I spent gleefully igniting items like “The Alien Fountain” and “The Naughty Dog.”

But no firecrackers—I hate firecrackers. Firecrackers are for pre-teens and convicts.

So no fireworks for me, not anymore. I’m older now. Wiser. Slower. More embarrassed to show up at the Emergency Room smelling like cordite with something scorched and dangling. Even if I still had the itch, fireworks are not an option here in Southern California, which is not so much a place to live as a large Triscuit with buildings on it. One “Naughty Dog” and there goes the neighborhood.

My first six years, we didn’t even celebrate the Fourth. The Larkins were not a celebrating family; life was too hard, and money too short. Christmas and Easter we’d get together, and it was pleasant enough, but I don’t remember even Thanksgiving being much of an occasion. Holidays were for rest—or, if you were really fortunate, time-and-a-half.

Things changed when my Dad came into the picture. The Gerbers were a celebrating family, and they took actual vacations, too. Vacations are a class marker, if you didn’t know already, and the lack of them yet another way we show our care for the less fortunate. When Dad was bartending, there were no vacations. But when we moved to Jeff City, it was possible—Dad’s new position as the only red-headed Swedish-American at an HBCU didn’t pay much, but it did give him those precious paid days off.

• • •

So beginning in 1977, every year around July 1st we’d pack up the car and drive eastward, to spend a week in Fairfield, Connecticut with his folks. Google says it’s 16 hours and 51 minutes straight through, and we did go straight through, adamantly, shaving off whatever time we could via speeding, and leaving early.

Most people wake up; my Dad explodes. The first fingers of light steal across the groggy landscape…and suddenly there’s music playing and coffee brewing and suitcases zipping and our dog Gus barking, and the stray cat zoomying, and Dad …singing?

No one is happier than my father at 5 a.m., no one more ready to go. No one ever in History.

To his credit, he held off as long as he could. Then at 5:07 he’d lose control and pound on my bedroom door. “Wake up, Mikey!” he’d shout gleefully. “We’re leaving in fifteen!”

I am fragile of mind in the morning, so my mother slid in behind him. “You can sleep more in the car.”

Especially in the early days, when we had the orange Mazda with a chewed-up back seat (thanks Gus) and no air conditioning, the trip was physically grueling. For one thing, the upholstery was black plastic, which heated up in April and stayed hot til October, and stuck to your skin like napalm. I remember that backseat being so crammed with luggage and boxes, I had no place to put my ass, just a sort of crash hammock made from beach towels and magazines and assorted other vacation detritus. I squeezed behind the passenger seat, a hard Igloo Playmate cooler went on my lap, and—

“Don’t put the fireworks in the trunk, Trish, they might get too hot.” So that box—tattered, ripped, maybe even sweating—got wedged in next to me.

If we got into a wreck, at least I wouldn’t suffer.

• • •

There I’d sit for fifteen hours, a MAD Magazine propped on the cooler as gale-force winds whooshed and swirled, til the beach towels around me snapped in the breeze. Did you know that some cars, if you open the windows on the highway, there’s a loud bam-bam-bam sound? I learned that, and how to pee into a narrow-necked Coke bottle, and how to use a hard plastic cooler as a pillow. Periodically, an adult hand would reach back. “Coke me,” and I’d fish down into the ice and hand over a soda.

The residents of Indiana and Ohio know that I speak the truth when I say both are excellent states to sleep through, especially if you’re eight and stayed up until one a.m. reading The MAD Adventures of Captain Klutz. Pennsylvania was pretty, but a deceiver. To a Missouri boy, Pennsylvania sounds like the East Coast—but that sucker is wide. That first year, Mom and I cheered as we crossed the border…then found to our horror, we still had six and a half butt-numbing hours to go.

Disheveled, sweaty, stinking of road food, we’d pull into Hill Farm Road near midnight, leaning on each other like survivors of Khe Sanh, simultaneously wired and sleepy, bodies hurting and minds dazed. Greg’s mom Caryl (hereafter called “Gram”) always waited up for us in her bathrobe, and we’d hug in her kitchen.

Like every kid, I was hyper-aware of the different way houses smelled, and the different customs families had. For any kid in a step-family, that sense is turned upto infinity. But Gram was always so incredibly kind and welcoming. She let me sleep in, for one thing. For another, she took me to the beach, let me fill a bucket full of treasures (a good portion of which turned out to be rotting crabs), and never, not once, made fun of me for being afraid of sharks.

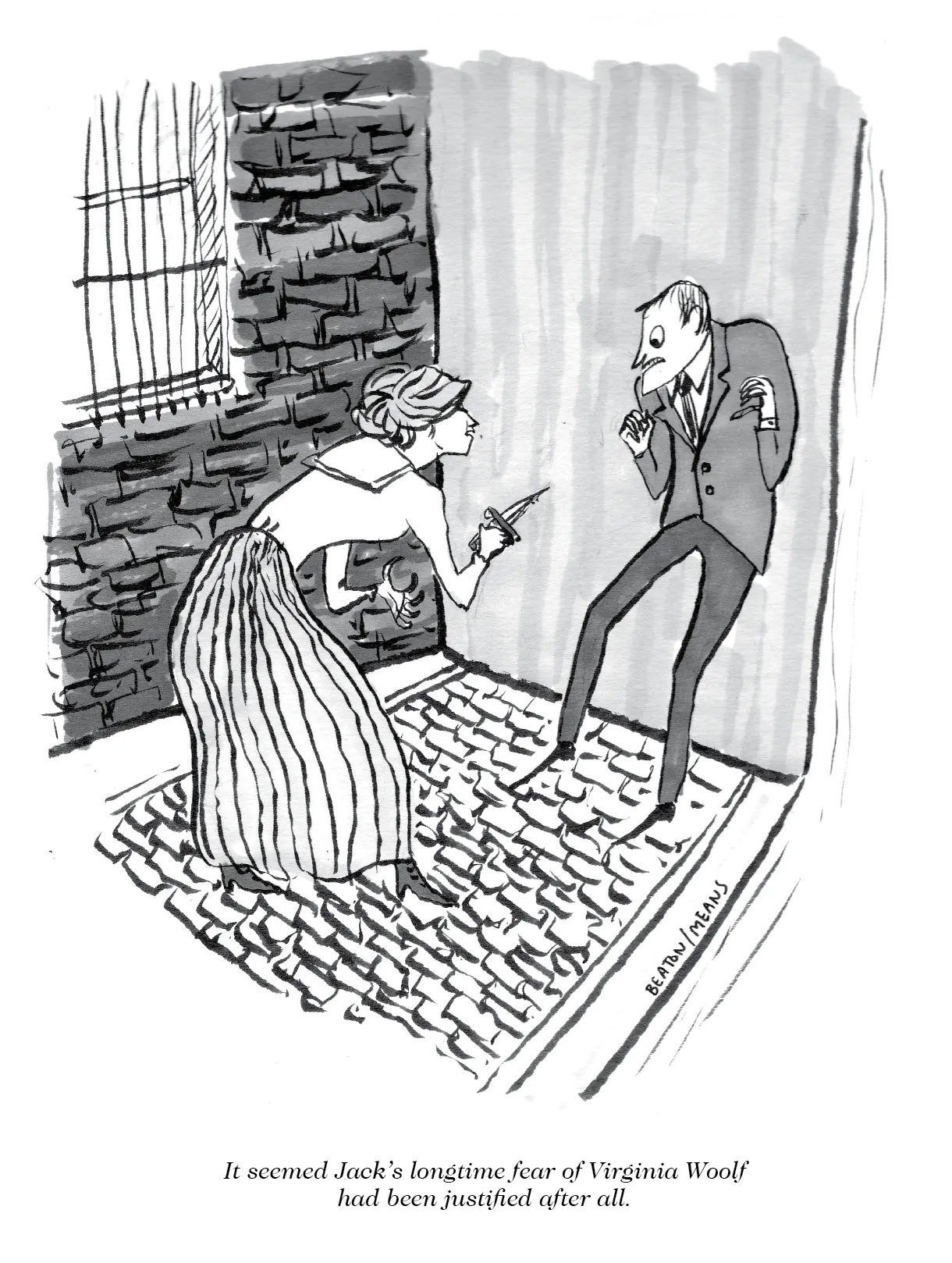

The summer before, at seven, I had read JAWS, undergoing an anxious, imaginative kid’s version of a bad LSD trip. The book utterly ruined the ocean for me, and large lakes, and ponds, and swimming pools and, occasionally, the shower. But in my defense, there most definitely were Great White Sharks in Long Island Sound. They were there cruising around in 1977, and they are there today, and if you don’t get your shit wrecked by them, that’s because they, like Bartleby the Scrivener, “prefer not to.”

Gram’s genius was that she treated me like a kid, instead of the demi-adult I’d had to be for my mom and I to survive. Fairfield was a cute little town (it still is), and she and I tooled around in the family Audi doing errands. She took me to the butcher shop. She fed me Goldfish crackers, and Schweppes ginger ale in little bottles. Pretty, with graying auburn hair, she was a wife and mother of a rather old-fashioned sort, and I—a sweet but intense little kid from a complicated family background—felt totally accepted from the moment I met her. This was a rare feeling for me. What a huge talent Gram had for loving; I see her in my sister, and my niece, and feel glad.

There were stakes to that first trip to Fairfield; as of July 4, my parents had been married for less than five months. Dad was only 23, and marrying a widow with a kid—double-diamond highest-difficulty matrimony, even for those loose-lovin’ days. On the day of, Gram had overheard me talking on the phone to one of my pals. “Sorry, I can’t play today,” I said. “My parents are getting married.” Gram quoted this for the rest of her life, but there was no judgment in it. Though Mom and I might worry about the rest of the clan, Caryl had claimed us from the beginning.

Dad is the eldest of three brothers. In July 1977, Kurt was home from college, a photographer, quiet but kind and slyly funny. Scott, the youngest, was still in high school and just ten years older than me. Tan and ripped from football and lacrosse, he carried a sense of fun with him always; in retrospect it was obvious he’d end up in California. Scotty took me up to his dark teen-den of a room and showed me his LPs. “Have you ever heard this one?” I don’t recall if I liked Live at Leeds, but I liked that he played it for me.

During these trips East, which happened every year for about five, Scotty would take me out with his friends occasionally. I remember one fishing trip that got a little rowdy—but Rocco and the gang found the dock eventually. They hadn’t done anything I hadn’t seen my parents’ friends do a thousand times, probably less skillfully. And unlike St. Louis’ Central West End, there were no cops in the Long Island Sound. (Only sharks.)

Dad’s Dad, Gramp, was gruff—I can only imagine what he’d think about how my life has turned out; actually, I can imagine it, quite precisely, but I choose not to. But back then I was just a kid, artistic tendencies mostly hidden, no mistakes yet, pure potential. So Gramp treated me nicely. We talked about sports. I could make Gramp laugh, though not always intentionally.

“Did you hear what that kid said?” he’d growl with a smile. “Out of the mouths of babes.”

Though to me he seemed the epitome of preppy manhood, with his “go-to-hell” patchwork pants and lime green golf shirt, Gramp’s relationship with Fairfieldness was complicated. Protective coloring aside, preppies were, to him, a special kind of asshole, members of a club he’d never truly belong to. He’d come from Ohio and, like Michael Germuth, ran away when he was young. Like so many kids, he’d grown up with not enough love, and still showed the scars. But despite all this Gramp had done well—in 1977, he was the President of a scale company, and to me an almost unimaginable wheeler-dealer. He’d been to Japan on business, and told me stories about it. “I have something for you,” he said, then reached into his desk and pulled out an abacus, which I kept for years. I was his first grandson, sort of, but he was definitely my first grandfather.

He played that role well, whenever his moods were clear. Once Gramp chartered a boat, and he and the boys and I all went fishing for bluefish out in the Sound. In the morning (which started early enough for my Dad to sing) the fish weren’t biting, and I remember bobbing up and down, wind whipping, no land in sight, listening to Gramp explain at length why being a fan of the Mets was “a sign of good character,” and being a fan of the Yankees was not. (Ironically, Gramp looked a lot like Mickey Mantle.)

In the afternoon the bluefish came in, hard, and we were suddenly getting one, two, three strikes on the big umbrella lures trolling behind the charter. These fish were big, and feisty, and in groups of three or four seemed to work together, pulling hard to elude capture. They were quite tough to reel in, even after the captain strapped me, Quint-style, into the chair.

When we got back to the dock, sore-armed but happy, I was instructed to call the house and inform Mom and Gram that we’d struck out.

“They just weren’t biting,” I said. “Don’t tell Gramp, but it wasn’t very fun at all.”

Gramp laughed behind his hand. “Tell them we’ll bring home McDonald’s,” he whispered.

The Gerber homestead was at the bottom of a hill, in a sort of wooded gully, so when we got to the top of the driveway, Gramp turned off the engine and we coasted in silently. While we got out as quietly as possible, Gramp walked around the back of the house to the sunporch “to keep the girls occupied.” Then Dad, Kurt, Scott and I lugged the coolers full of fish into the kitchen, and quietly dumped them into the sink. There were so many, they slopped outo the counter and slid too the floor. Mom and Gram were very surprised, and we ate bluefish, oily but delicious, for the rest of the week.

• • •

Once a trip, usually the second day we were there, we’d head into the city. In 1977, I took the Metro-North for the first time, a line I’ve ridden so much they really should name a stop after me. “…Stratford, Milford, Mike Gerber, and New Haven.”

I’ve never forgotten that first trip into Manhattan, during the “Summer of Sam” (a coincidence, I assure you). Those years are legendary for being the absolute nadir of the town and I’m here to tell you: people are not kidding you about that. Taxi Driver made it look a lot more glamorous than it was in real life. Literally the first New Yorker I ever spoke to was a guy standing next to me at the urinals of Grand Central Station. Pale, unshaven, with wild hair and even wilder eyes, he looked like Jerry Rubin at his most skeevy, and wore a stained Army jacket, the uniform of Seventies schizos everywhere, from Travis Bickle to Jim from “Taxi.” He watched me pee, rather closely it seemed, then said, “See that gum in there? Pick it up.”

Dad, standing on the other side, swore at the guy and told him to get lost. Then he turned to me. “Welcome to New York, Mikey. I don’t talk to anyone but mom, me, and possibly a cop.”

We walked up into the light, and my mind was blown. Sure, the whole place looked feral, in desperate need of a bath, but Manhattan in 1977 was wildly, unpologetically alive, like a coyote someone has put a T-shirt on. Every so often I’ll cue up a movie from that time, say Saturday Night Fever, or Marathon Man, just to remember all the chaos and color. So many people—old people with a kind of fierceness I didn’t see in the Midwest; people running hustles (Dad had to pull me away from the three-card-monte), and waves and waves of young folks, many of them now Trump voters. They looked like they needed a decent meal, but had spent that money on drugs instead. It was odd and uncanny to interact with so many people in an altered state. I entered an altered state of my own when we went to F.A.O. Schwarz, New York’s late, lamented toy store. Mom and Dad bought me a tiny red-bottomed sailboat, which we sailed in Central Park later, and a Corgi replica of James Bond’s DB5 from Goldfinger which sits on my desk to this day.

But the part of that first New York trip I really remember was going up in the Empire State Building. My Dad didn’t like heights, but it was his habit back in those days to deny such things. My Mom used that denial against him. “Michael will like it,” she said, “and besides, who goes to New York and doesn’t go up in the Empire State Building?” When it was clear that she and I were definitely going, Dad swallowed hard and came along, packed into an elevator, shoulder-to-shoulder with office workers and tourists.

When the doors opened on the observation deck, I was surprised to see how shabby it was. Wherever you looked something was rusty, or broken, or needed a fresh coat of paint. I shouldn’t have been surprised; this was the time of “Ford to City: Drop Dead” when the Bronx was burning, blackouts were common, and people didn’t think cocaine was addictive.

Still, the view was free, and on a bright sunny day in July, the city below looked gorgeous.

Gingerly, my Dad and I joined Mom over at the edge. She loved it; my Mom has always loved New York. “Are you okay, Greg?”

“I’m fine, Trish,” Dad shot back. He was a bit pale.

“I can’t see,” I said. “I’m too short.”

“Greg, would you pick Michael up so he can see over?”

After a moment’s delay, Dad said, “Sure.” Putting a hand on either side of my waist, he hoisted me up. The view was vertiginous, and wonderful. Here the chaos of the sidewalk resolved into the flow of a river—tiny cars, and tinier people, bustling about. It was fascinating. Losing myself for a moment, I leaned a little farther, reaching out to steady myself on the wrought-iron railing…which sagged over with a sickening creak, trickling rust on my hand.

As I pitched forward, I screamed. Dad also yelled, and yanked me back to the ground.

“I’ve had enough,” he said. “Have you two had enough?”

“YES!” Mom and I chorused.

When our souls had finally returned to our bodies, the elevator echoed with nervous laughter. “That was a close one, eh Mikey?”

The adrenaline stuck with us all the way up to the legendary ice cream restaurant Serendipity III, where it took a whole hot fudge sundae to calm me down.

• • •

We usually worked it so that the Fourth itself was right in the middle of the trip, the backbone of it, the pinnacle. That morning the boys would head off to some mischief—Kurt and Greg might go shoot photographs (and smoke pot), and Scott hang out with his buddies (and smoke pot), while Gramp would play golf (and definitely not smoke pot). As a little kid, I would go with Mom and Gram, popping around Fairfield provisioning a nice lunch, which we’d have out on the screened porch.

My family is crazy for screened porches, and I am too—everything good about preppydom can be summed up by a screened porch. It is real estate related, and leisure-focused. It is Nature tamed, surveyed from a flattering distance, enjoyed with a cocktail. There is never a time when I don’t wish I was on a screened porch; even as I type this, it’s true. Gram and Gramp’s screened porch, the first one I’d ever enjoyed, was particularly nice. It got morning sun, but afternoon shade, and the screens were tight enough to keep the bugs out as one surveyed the small but nicely landscaped backyard.

If there is a God, He surely surveys what He hath wrought from a screened porch.

Anyway, on the Fourth lunch was followed by napping and watching Wimbledon, activities which were to my young eyes indistinguishable. Then, after a few cocktails, we’d dress for dinner at the Fairfield Country Club—just khakis and a blazer, nothing terribly fancy, because the night would end up with everyone stretched out on blankets on the beach, looking up at the display. Gram would be sure to bring sweatshirts; she’d been doing this for decades.

But before then—before the wedding-style chicken and the bright green carpeting, and the cold sand that somehow got everywhere—we’d light off a few fireworks.

By “a few,” I mean the whole boxful that we’d brought from Missouri, where such stuff was legal. Every year, Gramp would send a not-inconsiderable chunk of change to my mother, who was charged with the grave responsibility of going to the fireworks store and filling a box with requests. Like I said earlier, this was no problem those first few years, when we drove. For me, it was a bit like Wages of Fear, with every pothole possibly my last, but Fate was kind and I survived.

Things got a little trickier when Dad’s fortunes improved and we began to fly. My mother had an uncomfortable scene at an airline ticketing counter when the box she was attempting to check, split and spilled fireworks all over the gate.

“Ma’am, is this your box?” Airline ticketing agent live for moments like this.

“Yes,” my mother said, turning red. (It would get worse.)

“And you marked it”—he peered at the box—“‘Toys’?”

“Yes.” I’d never seen Mom so mortified.

I locked eyes with the agent, and tried to appear as Dickensian as possible. In that split-second I saved Mom from the hoosegow.

“Well”—Ka-CHUNK!—”don’t do it again.”

Such was flying in the days before 9/11.

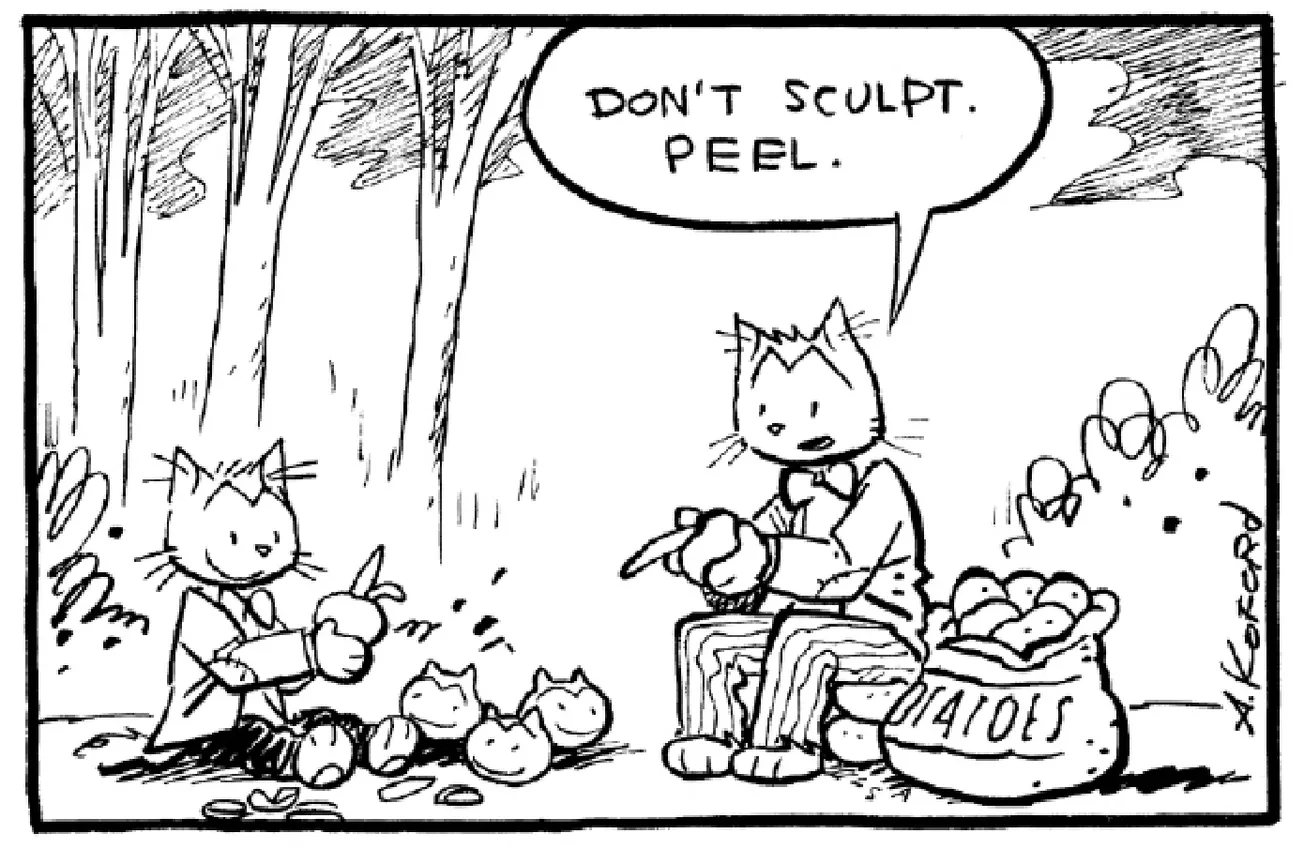

The evening’s festivities began with a thorough sweeping of the driveway by yours truly. “We don’t want anything to catch fire,” Dad said.

“Don’t we?” I teased.

“You know what I mean.”

Gramp would start off with small stuff—sparklers, firecrackers, maybe a hand-held roman candle or two. One of the boys might put an M-80 into a beer can, or toss a cherry bomb high into the air so it would explode mid-flight. Then, the larger items would be brought out—the true explosives, squat cylinders of multi-stage multi-color mayhem, fountains, mortars of all sorts, even one that shot out a toy soldier in a little parachute twenty feet into the air. (The chute immediately caught fire, and the soldier hit the driveway with a clunk.)

Gramp directed all the action. “Greg, it’s time for something big. No, not ‘Golden Shower,’ I think we need more punch. Try ‘Thor the Destroyer.’ There’s a punk over there…Scott, what’s that in your hand?”

“Heineken.”

“Not that!”

Scott read the Chinese label. “Fiery Brocade.”

“Sounds a bit light in the loafers,” Gramp smiled, then turned to me. “‘Fiery Brocade’, Michael—winner or dud?”

Before I could give my well-reasoned opinion, Kurt yelled. “Head’s up everybody!”

Dad lit the fuse and skittered away. “Fire in the hole!”

Sometimes they’d go off immediately; other times…silence.

Dad walked back towards the canister, softly, slowly. “Mikey, promise me you’ll never do this,” he commanded, as he moved forward cautiously, then poked the lightly hissing firework with a stick.

“Careful Greg,” his father said. “If you knock it over it’ll go right into the house.”

“C’mon Dad!” “Jesus!” “You do it!” All three sons grumbled as one—then it caught and exploded.

All five of us were utterly delighted, but Gramp most of all. “Whatever we paid for that one, it was worth it!” he said. “Did you see it? Did you see the green?” Gramp watching fireworks was Gramp at his best. He was like a kid—maybe the kid he’d never gotten to be in the first place.

After about ten minutes of the good stuff, the kitchen phone would ring; a neighbor would be calling about the noise. I would be dispatched up to the top of the driveway—as I said, the house was in a sort of gully—with clear instructions: “Look both ways down the road. If you see any cops, stall ‘em.”

Meanwhile, the charred paper and other evidence would be swept up and placed in a wheelbarrow to smolder. “Caryl, dear,” Gramp would call out. “You didn’t tell them it was us?”

“Of course not, Larry dear.” This was not her first rodeo.

When a few minutes had passed, and the coast was clear, Gramp would whistle. I would stiffly galumph my way down, and we’d light off another round. This cycle repeated until the entire box of fireworks was gone.

Every Fourth of July for the better part of a decade, I saw my grandfather straight up lie to an officer of the law. “Hey Larry, there have been reports of fireworks in the area.”

“You don’t say,” Gramp would growl merrily, shaking his martini clink-clink.

“You wouldn’t know anything about that would you?”

“Absolutely not, officer,” Gramp would say. “Fireworks are illegal.”

“What’s that burning smell?”

“Just a few sparklers.” Gramp turned to me. “You lit a few sparklers, didn’t you Michael?”

“Yes, grandfathuh,” I said, wide-eyed and nodding, enunciating like the perfect preppy kid, really putting it over.

After the cop had trundled back up the drive, Gramp put his arm around me. “’Yes, grandfather,’” he said, chuckling medicinally into my face. “The Larchmont lockjaw was a great touch! Great!”

That’s when I knew I was part of the family. ◊

MICHAEL GERBER is the Editor & Publisher of The American Bystander. He is writing a memoir, which will published occasionally here before it’s a big ol’ book.