Longtime readers of this blog know that I am a huge supporter of student publishing. I think student publications will be the seedbed for the post-corporate media our country (and world!) so desperately needs.

This morning, I was reading my friend Adrian Bonenberger’s feed on Twitter. Adrian’s been highlighting the treatment of student journalists during the campus protests, and this tweet of his really hit home for me:

The finest school in the world for studying journalism is at an American university that is openly contemptuous of journalism. Like the protests or hate em, we should all agree that student journalists have the right and obligation to cover them — with university support”—@adrianbonenber1, 5/5/24, 8:53 am

Seems pretty simple to me: If Columbia University is an educational institution, and not merely an investment vehicle masquerading as a finishing school, it should allow its student journalists to cover campus events without restriction. They’re smart and thoughtful, that’s why you admitted them! So let them report what they see, and say what they think.

One thing—maybe the best thing—Yale University taught me was the relationship of publishing entities to entrenched power, and how “bigness,” far from being a mark of power, could create a profound weakness. When I was a student there in the late 1980s, another era of protest and divestment (then over South Africa), Yale had placed lots of subtle checks on The Yale Daily News (real estate, ad buys, YDN alums on the Corporation, etc.) ensuring that it would never be a real thorn in the side of the Administration. This system “worked”—there was the appearance of a free press, but campus comment stayed within pretty narrow bounds; student journalists were trained exceedingly well, but not adversarially, so they got plum jobs at prestige papers after graduation. As much as I liked individual reporters and editors, the YDN didn’t have to discourage iconoclasm, because iconoclasts didn’t join it in the first place.

But in 1986, the Woodward-and-Bernstein spirit wasn’t entirely dead in our culture, and this led to the emergence of a scrappy student weekly, The Yale Herald—which within three years of its founding, was given nice Yale-managed office space on campus, and a lucrative University contract. The Herald, predictably, sprouted infrastructure to fill its new circumstances, and suddenly was one angry administrator’s phone call away from bankruptcy. So from The Herald, I leapt to The Yale Record, Yale’s student humor magazine.

Yale’s attitude towards The Record had been bareknuckled for decades; in 1948, it had evicted The Record from its building, at the behest of the University’s head of PR—The Record, it was felt, was bad for Yale’s brand. And in the Seventies, when Yale stepped in to save the YDN, The Record was left to wither. And wither it did…until desktop publishing allowed me and my crew to put it back in business. The Yale Record is now a profitable monthly, run by students and completely independent from the University.

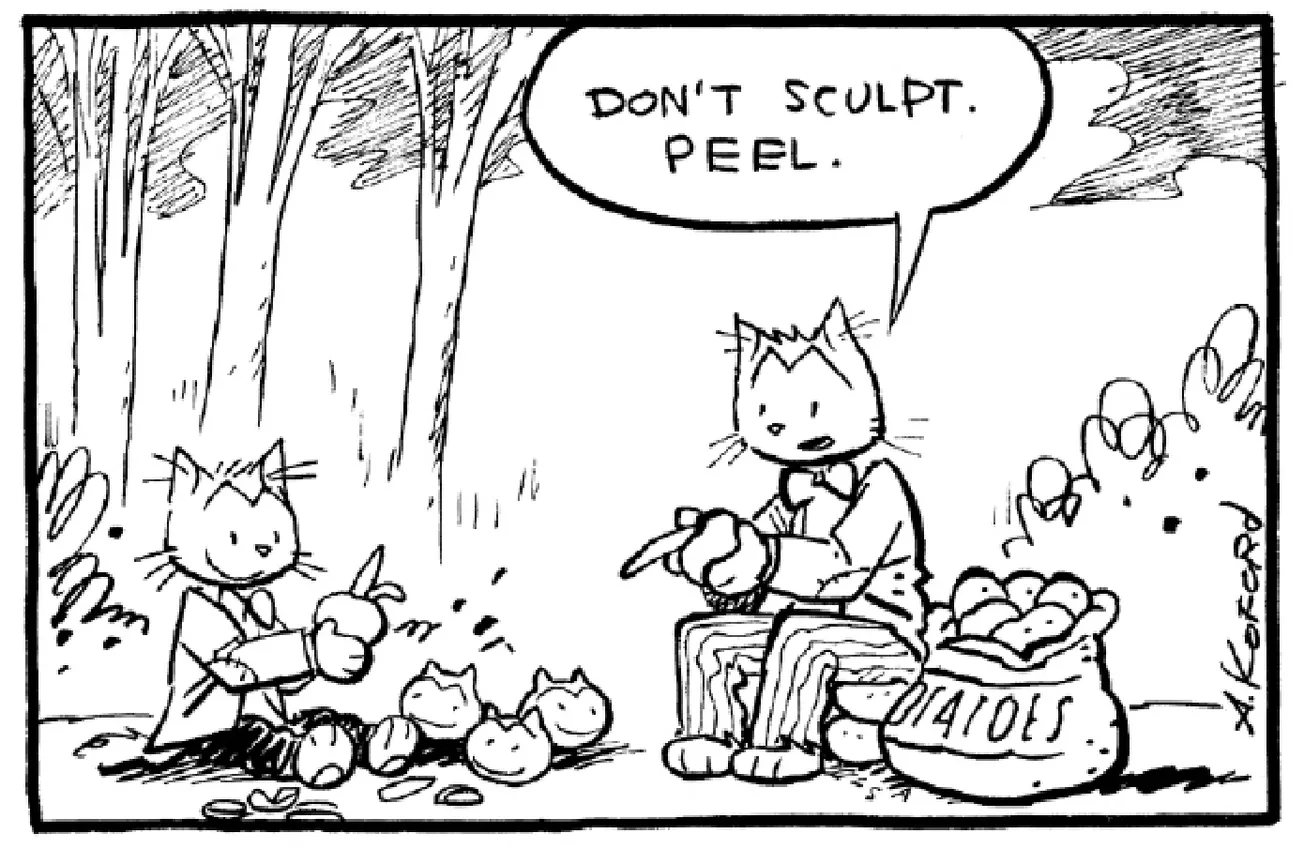

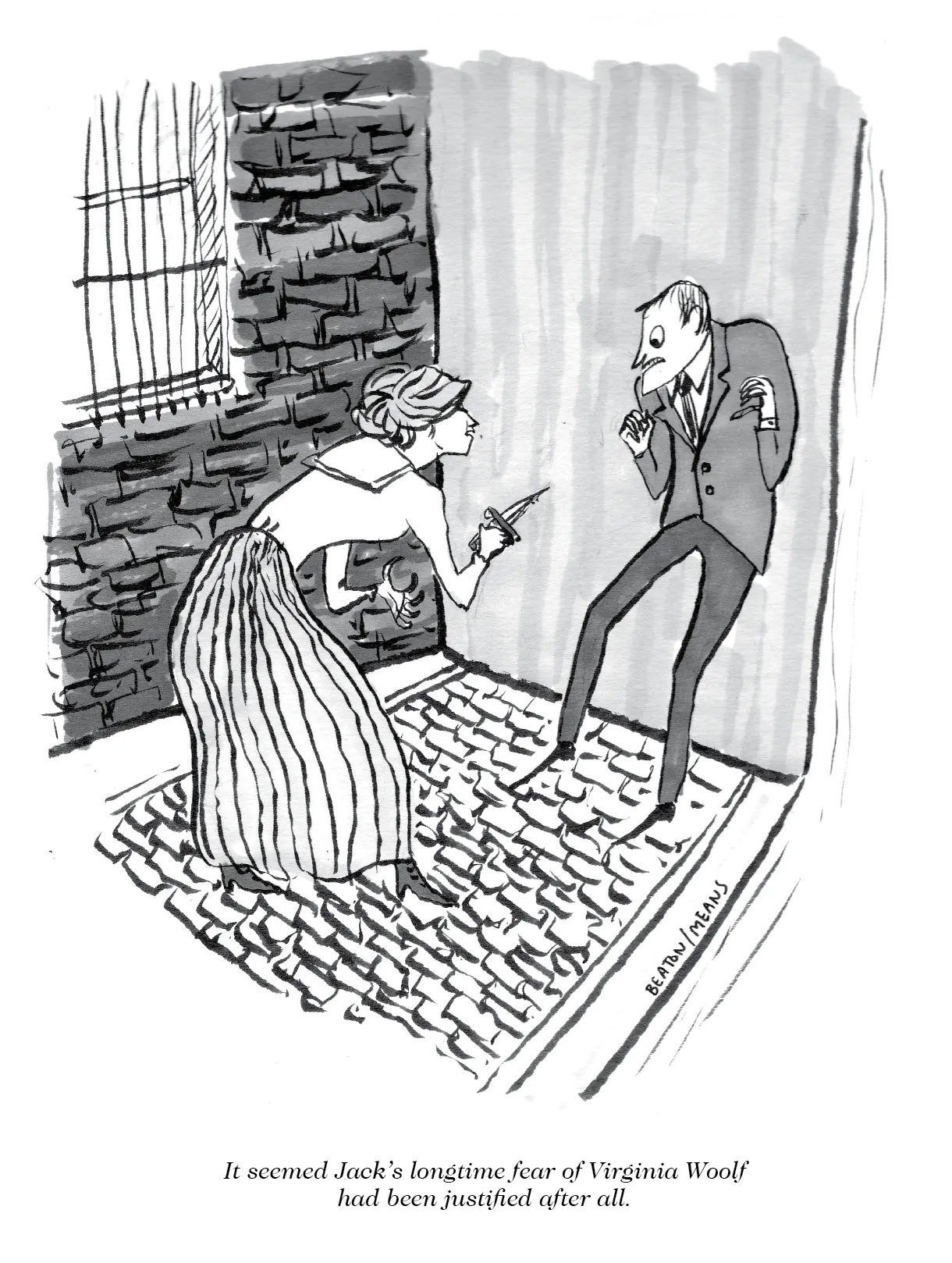

This experience has given me an obsession with what I call “micropublishing,” publications by and for small communities which are super-easy to run and pay for, and super-hard to suppress. For 35 years, I’ve continued to refine The Record’s model, and that post from Adrian—another Record rabblerouser—makes me think that I can be of some service to whatever communities, student and otherwise, might need it.

Print does two things extremely well:

1) It focuses. A print publication is a group endeavor, and it’s a one-way method of communication that the creators control. Just like social media is designed to have individuals make statements—and then have other individuals chime in as equals, often hijacking the conversation—print is designed to weld a group of like-minded people together, allow them to report facts and/or refine ideas, and then present them to the public.

2) It formalizes. The moment you become a print publisher, you have a context, a history, and (one hopes) legal protections that come from centuries of print publishing before you. There is, even today, some faint flicker of respect for words on paper. Spouting off on X under a pseudonym is a completely different experience than reporting on something important, and signing your real name to it, even if you just staple it to a telephone pole.

The story of the 1960s counterculture would not be known today had it not been for “the underground press.” Then as now, mainstream coverage was massively distorted by advertisers, owners, and politicians. Unlike today, you could not print ultra-small quantities of a magazine or pamphlet—but back then, there was both infrastructure developed for mainstream publishing (plenty of idle printing presses, cheap newsprint), plus a culture within journalism and printing that was pro-labor, adversarial to power, and at times radical. And so the underground press—and then alt-weeklies—sprang up naturally after 1964.

Today we have social media, which is very good at disseminating snippets of information, and welding together people with extreme views. It is not very good at conveying nuance or resisting censorship (insult Elon and see what happens); nor does it offer a way to make a buck, so that you can keep the reportage going. Seems to me that good old words on paper (and PDF) might really help us today. The principles of micropublishing can be used to produce almost any type of publication, from flyers on telephone poles, to something slick and professional like The American Bystander.

So over the next few days, I’m going to do a few short videos explaining the nitty-gritty of micropublishing—what it is, and what it can do for you. I’ll even do a few quick template designs that people can take and use as their own.

Whatever one’s stance on the situation in Gaza, I’m sure we can all agree that a truly free press is one of the bulwarks of democracy, and an unalloyed good. And as painful as it is, it is an excellent thing for student journalists to see the true priorities of institutions. Too many journalists of my generation, especially those who went to high falutin’ schools like Columbia or Yale, have spent their careers believing they were “in the club.” We’ve all suffered a lot for that coziness. What this country needs is a million new tiny publications, each making one dollar more than they need. I’d like to help that happen, so watch this space.