I realized after interacting with many of you on last week’s poll question (“Has a joke ever changed your mind?”) that many of my strong opinions and attitudes about this stuff come from things we’ve never talked about. Well, let us begin then. As I said in one of my responses, that poll actually began as an essay on Lenny Bruce and Mort Sahl and how both of them had a deep, child-like faith in an external authority willing and able to dispense justice. We’ll get to that in a bit.

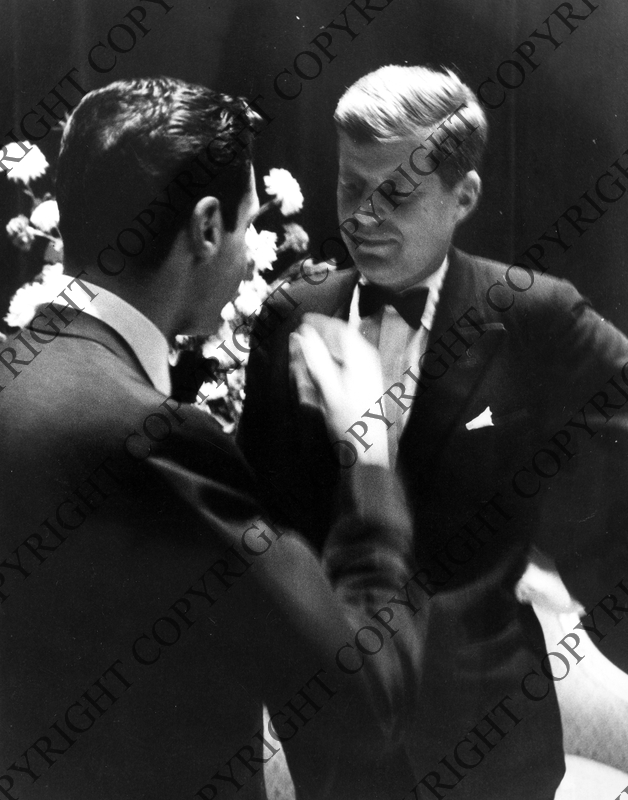

But first, this: So much of our current conundrum—in comedy, in politics, in culture—began with John F. Kennedy. JFK was the first President-as-Movie Star.

Or vice-versa, and therein lies the problem: In America since Kennedy, where does politics end and entertainment begin? If it’s all entertainment, at what point does sound governance, subtle diplomacy, statecraft, omnibus infrastructure bills and all the other boring grownup stuff even happen? It matters, we all know it matters—so why can’t we care about it? Prior to November 1960, we judged politicians and movie stars very differently, and recognized that very different talents and temperaments were required for success. To expect that Rock Hudson or Cary Grant could responsibly manage the Nuclear Triad was as silly as dismissing Dwight D. Eisenhower for being blown off the screen by Doris Day in Pillow Talk.

Then JFK came along, in Norman Mailer’s words, with “the deep orange-brown suntan of the ski instructor, and when he smiled at the crowd his teeth were amazingly white and clearly visible at a distance of fifty yards.” Superman Comes to the Supermarket. JFK had the brains and background to run a country, and the good looks, panache and humor we hadn’t known we’d been missing. Mailer again, writing in 1960:

“His appearance changed with his mood, strikingly so, and this always made him more interesting than what he was saying. He would seem at one moment older than his age, forty-eight or fifty, a tall, slim, sunburned professor with a pleasant weathered face, not even particularly handsome; five minutes later, talking to a press conference on his lawn, three microphones before him, a television camera turning, his appearance would have gone through a metamorphosis, he would look again like a movie star, his coloring vivid, his manner rich, his gestures strong and quick, alive with that concentration of vitality a successful actor always seems to radiate. Kennedy had a dozen faces…like Brando, Kennedy’s most characteristic quality is the remote and private air of a man who has traversed some lonely terrain of experience, of loss and gain, of nearness to death, which leaves him isolated from the mass of others.”

Mailer compares JFK, war hero and politician, to a mumbling actor famed at the time for driving the girls wild. This would’ve been quite a diss even twenty years before, like comparing the crowd’s reaction to a speech by FDR to Frankie’s swooning army at the Paramount. But Mailer’s comp is entirely apt; JFK was a star—even his detractors admitted that, and called him a lightweight for it. They still call him lightweight, and load him up with what the Dulles brothers did in Cuba, and what Johnson and Nixon did in Vietnam. The thing about being killed at 46 is your enemies can say you would’ve been just as stupid as they turned out to be.

But all this is just the trauma talking; the people most committed to the JFK-as-dumb-rich-boy idea are people around my age, Gen Xers or late Boomers who grew up with the CIA/FBI leaks of all his affairs (“Judith Exner Campbell speaks! Today on Geraldo!”) , and suspender-clad Reagan-era teardowns of whatever liberal icons we had left. “He wasn’t so great!” “What about the sex, do you approve of that?” “People just need heroes!” Yes, they do, and within three months of my typing this, there will be another special issue in my grocery store with JFK’s face on it. Imagine thinking that kind of undying charm makes a politician less powerful, less important in the story of a democracy.

But okay—charm aside, strictly as President, how did Kennedy do? Well, he saved the world during the Cuban Missile Crisis, that’s beyond debate. The Bay of Pigs was at least 50% Eisenhower, and Vietnam was more than 50% Johnson. The Russians bullied Kennedy at first, but he soon got up to speed, moving towards detente, ten years early. He was slow on Civil Rights, for sure, but came around. The Moon stuff, a nice touch. JFK’s endless promiscuity was profoundly sleazy and a security risk, and might have eventually cost him the Presidency in a Profumo-like scandal. But as I said, he and Bobby saved the world—so I’d give him a solid “B,” with a year left to go. A movie star? Maybe, but not just a movie star. Looking at his Presidency straight on, JFK had a learning curve but was not a lightweight, any more than Barack Obama was when his detractors said the same. Incidentally, Obama always struck me as a new, improved version of JFK—a better man, certainly—who by the end, had transcended any comparison. But will Barack Obama be gracing grocery racks in… 2076? Somehow, I doubt it—and maybe that speaks well of Obama, and of future Americans, too.

JFK, like Obama, could tell a joke—The Kennedy Wit. (Had Bystander been around in 1960, we would’ve printed The Nixon Wit but with 120 blank pages.) Speaking of Nixon, you can understand why he was so salty—it’s not his fault he wasn’t equipped for this brave new world, no Republican of his generation was. For that they had to tap Ronald Reagan, an actual actor. Jimmy Carter’s big problem was that he was truly an exceptional man—he just couldn’t play one on TV.

American politics between the Age of Kennedy and Age of Obama could be efficiently summed up as one big national Star Search. (Mort did a good bit on this, here.) Clinton seemed to satisfy, for a while, but in the end the comparison seemed forced; Clinton never had Kennedy’s dignity. Obama does, and I think (I hope) he scratched our national Kennedy itch, though we won’t be sure for a few more cycles. It really won’t leave us until everyone who was alive on November 22 has joined JFK in the Great Beyond.

I don’t think we’re quite aware we’re doing this, any more than a phobic knows exactly why he picks certain streets over others. Way back in 1990, when I was a senior studying History at Yale, I wanted to write my big graduating paper on the idea of the Kennedy assassination not as a whodunit, but as a national trauma, because I couldn’t make any sense of American politics since 1963 without it. We were being haunted by JFK, with post-Kennedy Democrats either being safe-feeling anti-charismatic figures or sweaty Kennedy-clones. I think this is even truer today; American thinkers and historians grind away uselessly, decade on decade, as wrongheaded as a therapist trying to treat a dog-fearing patient without asking, “Well, were you ever actually bit by a dog?…You were? Holy shit!”

Yes, we were bit, several times, and we think about it all the time, whether we realize that or not. The pull remains, the stone is still in our shoe. Even the rise of someone as fundamentally preposterous as Donald Trump, Kennedy’s opposite in so many ways, loops back into this gnawing national anxiety. Trump’s (possibly vaporous) wealth and gold-toilet strainings at glamor; his womanizing (and his fans’ approval of this); his jet; his “dynasty”; his “compound at Bedminster”; Jack had Marilyn, Don had Stormy. And if it isn’t perfectly clear, Q says John-John’s coming back to be Veep.

Trump as dollar-store JFK…the mind rebels. But I have to give him credit—in his Biff of the Flies way, Trump got the lesson of American politics since 1960: if you are entertaining, they let you do it. If America does narrowly avoid Fascism, it will be only because our strongman wasn’t handsome enough, charming enough, didn’t know how to tell a joke. Those are the ones we have to watch out for, the ones who can tell a joke. Or who hire people who show them how.

And this is where, finally, we come back to Mort Sahl.

• • •

“[JFK] was like an inquisitor. Somebody would say, ‘Who are you after, and what you pursuing?’ and Kennedy would say, ‘Everybody.’”— Mort Sahl, 1993

Mort Sahl, the ironist, the entertainer, the skeptic, nobody’s fool, looked at JFK and saw…himself. The genius politicians, that’s how they operate, and Sahl fell for Kennedy, hard.

When Kennedy ran for President in 1960, Mort wrote material for him—including a witticism that has gone down in history: “I just received a telegram from my father. ‘Don’t buy a single more vote than is necessary. I’ll be damned if I’m going to pay for a landslide.’”

But when JFK became President, Joe Sr. didn’t like Mort’s tone, and so (according to Mort) a blacklist began. Sahl’s income plummeted; even so, when the President was murdered in Dallas, the comedian was devastated. Most people to the left of George Lincoln Rockwell were; there was not, as there would be today, a large contingent of Twitter edgelords declaring they were too cool for grief. “Never liked the dude, big teeth, looked like a ski instructor, seemed sus.” In 1963, you could still afford to look at politics as something more than lifestyle, more than entertainment.

But that was changing, and quickly; the self-protective blast-doors of irony were being forged. On the night of the assassination, in front of a pre-cringing crowd waiting to see what “dirty Lenny” could possibly say, Sahl’s main competitor took the mic, paused for a long beat, and then finally said, “Whew. Vaughn Meader.” (Meader was an impressionist who’d risen to mega-stardom with an impersonation of JFK.)

The following week, Lenny would address the facts of the assassination directly. After studying the Zapruder frames arrayed in LIFE, he declared that Jackie’s climb onto the rear of the limousine was her “hauling ass.” And we should acknowledge this, “because when your daughters,” Lenny said, “if their husbands get shot, and they haul ass to save their asses, they’ll feel shitty, and low, because they’re not like that good Mrs. Kennedy who stayed there.” It was a funny bit, but reality had already shown itself to be much sicker than the Sickest comedian. Jackie, in her limbic confusion, had actually been reaching for a shiny white fragment of bone that had been blasted from her husband’s skull.

What happened in Dealey Plaza showed the fundamental unreality of politics-as-entertainment—politics was not just a movie you could watch, or a club you could join, but something serious, even deadly. And Bruce’s initially defaulting to show biz, the tinkertoy world of falseness and play, then pivoting to a factually wrong, philosophically driven “take”—this showed the fundamental inability of satire, no matter how Sick, to metabolize certain high levels of violence. Bruce and Sahl suddenly faced an existential question: what did satire mean in a world so savage? Surely there was some sanity, somewhere? Some justice, some authority one could appeal to? Some judge that would finally let Lenny do his act. Some other judge that would send CIA’s James Angleton to the chair for the murder of the President.

The rest of both men’s lives—one very short, one very long—would be a painful lesson.

• • •

Within a year of the assassination, both Lenny and Mort fell into kinda the same act. Lenny would bring up a briefcase full of transcripts from his latest obscenity trial, Mort would haul out the Warren Report. Audiences glazed; bookings dried up. Both men surely felt this as pain—they had, both of them, scaled the highest heights. But even more than the rest of us, the violence knocked Mort and Sahl off balance. They dropped the satirist’s mask and began to teach. For them, things had gotten too fucked up to joke about.

Lenny’s struggles came to a quick and tragic fruition; Mort’s story was more complicated. By the time Lenny died in August 1966, Mort had his own TV show in LA, where he began once again digging into the facts of the assassination. The show was cancelled, so Mort went down to New Orleans, where District Attorney Jim Garrison was heading up an investigation (later immortalized in the movie JFK). Sahl offered his services as a researcher, and stayed in that job for several years, albeit with respites like this segment from 1967, which show that his comedic chops were as sharp as ever. After the Garrison case ended, unsuccessfully, in 1969, Sahl remained close to the DA. You can hear the two talking here on Steve Allen’s show in 1971, which will give you a reasonably brisk outline of their take on the murder.

Before you ask: I began reading about the JFK assassination from the age of seven, and stopped at 42. I do not know who shot the President, and why. I think it’s highly unlikely that the Warren Commission is correct, because it wasn’t designed to be a criminal investigation. It was a political body, put together by political men for political purposes, and delivered a pre-determined result, the only politically palatable one. Oswald might have acted alone, but we will never know. If one is looking for an alternative “solution” to the murder, I think John Newman’s suggestion that there was a very small plot centered in the Counterintelligence Desk at CIA, with genuine fear of nuclear war as a passive motivator for suppression and coverup, is a reasonable one.

But more than any of that, I believe that the assassination—and the other murders of the Sixties—will never be solved. And because of this, they still gnaw at us; they knocked us all off-balance, and with every circling of the Sun, this imbalance has grown. Since 1963, and even more since 1968, our politics have been depressed and desperate, an uneasy, excessive exercise in distraction and entertainment, with nobody thinking to ask, “Hold up. You’re acting weird. Were you ever bit by a dog?”

And our satire and our satirists get blacker and bleaker, trying to anesthetize our pain as it grows and grows.

• • •

What does a satirist do when he is armed with the facts, but there is no justice forthcoming? In the case of Sahl, he gets more bitter and furious by the year. Though Watergate briefly brought him (paranoid, angry) back into alignment with the (paranoid, angry) zeitgeist, this did not lead to any lasting success. For all intents and purposes—as a force in comedy—Mort Sahl’s career died on November 22, 1963. In the mainstream, he was speedily replaced by people like Cosby and Allen and the young Pryor; later, the counterculture vastly preferred George Carlin.

Carlin’s Seventies comedy is, I believe, an attempt to learn from Bruce and Sahl’s experience in the Sixties—or more precisely, feeling that sense of “off-balance” inside himself, and trying to fix it with jokes. It’s an impossible task; national grief, the imperiling of democracy—these are things too big for satire to fix. So Carlin and satirists after him always turn to something smaller, something within our control: the rules of entertainment.

“Seven Words You Can’t Say on Television,” Carlin’s signature bit, seems subversive, but… Listen to this; Carlin’s stated intent is to free us from our hangups about these words, because they’re “merely words,” man. But he knows, as any storyteller knows, that they are not merely words—these seven profanities are an extremely powerful set of images, feelings and associations, which is why people are laughing when he’s saying them. Bruce engaged in this same kind of self-deluding sophistry, too, insisting that he was just trying to get us all hip—while enjoying the emotional power of taboo. (To be clear, I’m not arguing in favor of censorship. I am arguing in favor of being forthright and honest about what words are and do, if you use words for a living.)

Carlin’s “Seven Words” is both theoretical—pure semantics—and also focused on something artificial and low-stakes: television. TV is like life, only much, much smaller. Carlin’s literally using the words on stage, in real life, words we all use in personal speech all the time. His issue is you can’t use them on TV, and this is surprising why? Most important things, most of life in fact, cannot be pushed through the small pipe of corporate-owned televised media; to desire TV to be “truthful” or “not hypocritical” or “real” contains an assumption that it isn’t fundamentally narrow and small and artificial, and that it can be better than the corporations who make it, own it, and pay for it. Carlin doesn’t like being reminded that TV isn’t reality, and that’s why the different rules bug him and feel illogical; they tweak that “out-of-balance” feeling. Since everything is entertainment, if you fix entertainment you fix the world, and balance will return.

Bruce opining from a nightclub stage in 1962 might reasonably think that freer use of profanity could improve our mental health. But if Carlin really felt in 1972 that anything would be solved by swearing on TV, he was naive. And by the time of his HBO specials twenty years later, it was clear he was wrong. (Must’ve missed that bit.)

Carlin rolls back our national movie to before it went wrong; he takes Bruce’s JFK-era obsessions—public/private, “clean”/“dirty”, the fundamental dishonesty and arbitrariness of propriety, which is used to control and hurt people—and updates them for a generation that views entertainment as the thing, the only thing, because it’s all they can control. Fair enough; but after Dallas and everything else, it’s just a bit, and that’s why Carlin can do it. We all know that nobody in Carlin’s audience is truly bothered by those words in 1972, not like some in Bruce’s audiences were in 1962, and the bloody decade in between is why. Yes, Carlin got arrested seven times for doing the routine; but his career thrived. By 1972, the whole thing seems like a carefully choreographed dance of cops versus hippies, Right versus Left, both performing for their constituencies, miming repression and rebellion, with nothing very much at stake.

Which is where we are today, only even more “off-balance” than ever.

• • •

I’m fully prepared to own all this as my private obsession…but in my defense, it was Bill Hicks’ too. He also knew something was up; he was obsessed with the JFK assassination, and talked about it at length. I think we both figured out that a democracy where elected leaders can get shot, the government investigates itself, finds no flaws, nobody gets fired and everything goes on as if nothing happened—that’s about as real as a Broadway musical. Something’s off-balance here, you feel it too, don’t you Bill?

Politics as entertainment, entertainment as politics…How does one do satire in an era where people with vast power and authority can be not just your old-fashioned fools, knaves, and hypocrites, but out-n-proud adulterers, money-launderers, rapists, sellers of secrets, traitors, Christ even perhaps actual spies—as long as they entertain us? If JFK’s connection with Ellen Rometsch had come out in 1963, he wouldn’t have lasted until the weekend. Now—will Trump be prosecuted for stealing secrets, and almost certainly selling them? Who even knows? We are in deeply weird territory these days, friends, the product of decades of widening gyre. I know it’s in poor taste on Marilyn Monroe’s birthday to hold JFK up as any kind of hero, but—he was no Donald fucking Trump.

If we’re determined to entertain ourselves to death, can we at least have better taste in shows?

I think the JFK assassination broke a lot of things in America, threw them out of whack. We began viewing politics as entertainment, just in time for The New Frontier to change from stirring historical epic into PSYCHO. To get over the shock, we started using satire as a painkiller, but turns out if you take too much for too long, it becomes a narcotic. The movie’s gotten more and more chaotic, and now we’re having real trouble following the plot. Now we’re addled, addicted, a raw nerve, unsure whether the next scene’s going to be sexy or funny or terrifying. What happens next is anyone’s guess.

It’s nerve-wracking. If free citizens live with the anxiety for too long, they’ll do anything to make the movie stop—even Fascism. People like Ed Lansdale, CIA men who specialized in destabilizing regimes, knew this. Whether Lansdale was involved in JFK’s death or not, it’s foolish to pretend that we aren’t living in “a destabilized regime,” and that some part of our insane politics is this craving for quiet, order, a movie that we can watch in peace.

For Carlin, the price of this anxiety was heart attacks—in 1978, 1982, 1991, and finally in 2008. During this period, he gets angrier and angrier, more vituperative and misanthropic—and more and more popular. He comes out in favor of Planet Earth shrugging off humanity and his crowds hoot and holler, as if they aren’t living here themselves. We have left the realm of reality entirely, and are now only in entertainment, looking for a story that calms us, even if that story ends in human extinction. After decades of trying, Carlin’s finally touched on an authentic truth, one which hastened Bruce’s demise, and drove Sahl mad. It incites Carlin to fury; there’s the Iraq War, on his TV, broadcasting this truth for anyone who cares to look. It’s bracing, and barbaric, and sad. Because there really are seven words you can’t say on television:

“The President got shot and…that’s entertainment?”