BY RON HAUGE • I’m pretty sure The Ren & Stimpy Show is the only place I ever worked where the showrunner and his executive producers had such a terrible working relationship, they were all in therapy together. I’m not saying that’s the only reason the show was good, but I know it helped. Not the therapy part; the need for therapy part. The therapy just drove the showrunner to further madness. And madness drove the show. So, O.K., I was wrong—the therapy “helped.” But only by not helping.

Here’s how I got the job writing for the show: I was writing for another animated series on Nickelodeon when I went to a Nick party and ran into the showrunner at R&S, who was an old acquaintance I admired from the ’80s New York cartoon world. Within seconds, I was telling him all about how I was not fitting in at my current show, and how I expected to be fired any minute, possibly at the party, which was the only reason I’d made an effort to come. I told him the show’s creator hated me so much, he once asked his young female assistant to leave the room before he would respond to one of my story pitches.

My new savior was delighted. “You gotta come work for us,” he said immediately. Then he insisted that his executive producers hire me. He didn’t tell them it was because I was trouble.

The showrunner at Ren & Stimpy was talented and dedicated and daring, and mighty charming when he wasn’t being an ornery Texan — which, in fairness, was only about 8 percent of the time. (His wife’s figure on that may vary.) I loved working with him because he would fight to the death for anything he thought was good, and he produced a ton of good. He didn’t want to hear any ideas that would water down the show. That led to openly defying and even mocking his mild-mannered producers, who as Nickelodeon execs had to be super-calm and child-friendly and reasonable and nurturing in response or they wouldn’t be Nick. Also, they were aware that no one else on the planet could do the job.

I was the first staffer on R&S to work solely as a writer, not as a staff artist who wrote. Apparently that puked in the face of the series’ creator, John K., who had been ousted not long before I arrived. On my first day, I was introduced as the new writer at a large staff meeting, and the only comment from anyone was from an angry-looking artist who said, “Yeah, whatever happened to John K.’s idea that if you can’t draw, you can’t write?”

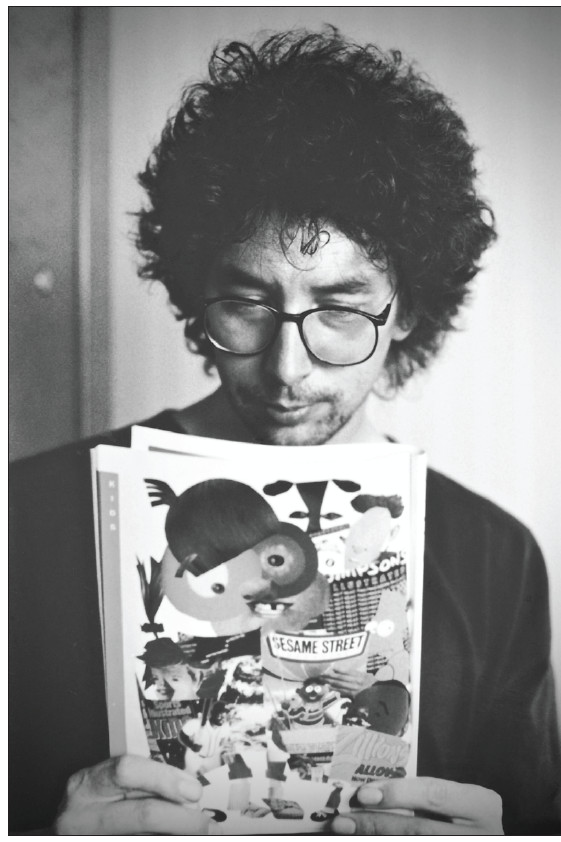

He hadn’t been told that I had been a working artist for years, for The National Lampoon and other magazines.

Or maybe he knew my work and still held the same opinion. “Don’t hate me because I’m a writer,” I told him. “Hate me because I’m me.” And when the dust finally settled, I’m proud to say he did.

•

As it turns out, hating-and-complaining was simply a way of life at The Ren & Stimpy Show. Everybody (except the super-positive execs!) hated anything or anybody that wasn’t one of the original Looney Tunes directors — including flawless new episodes of The Simpsons, promising new hires in the art department, another director’s outstanding new episode, the cultures of every European nation, beautiful actresses in particular and the remainder of humanity in general. It wasn’t personal in that it was always personal, so it was fair.

I later learned that everyone on the creative staff was there because they had been fired—rightly—from another show. We were The Island of Misfit Disgruntled Former Employees.

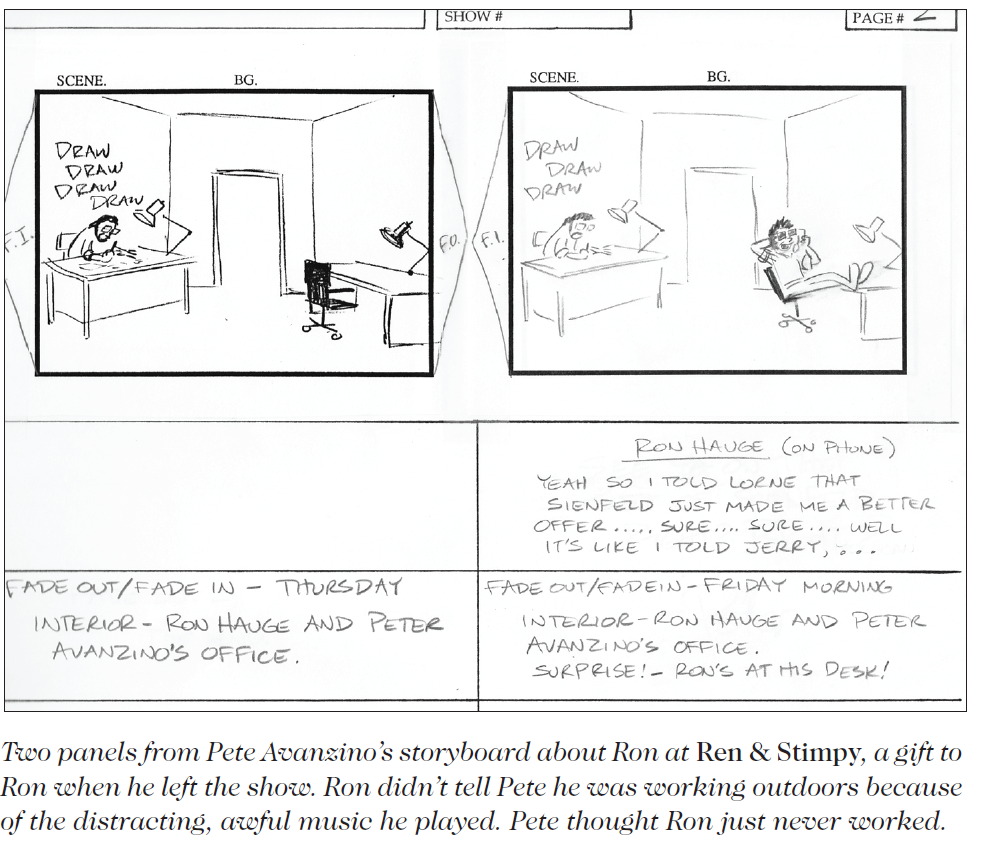

Because there had never been a writer on the show before me, there wasn’t a writers’ office when I got there, so I was given a small desk in the office of one of the storyboard artists. The artist, Pete, was the nicest guy in America — but he liked to listen to music while he worked, specifically the stylings of Blossom Dearie. If you’re not familiar with her extensive songbook, I suggest you listen to three or four seconds’ worth to get the idea. DO NOT LISTEN FOR A FULL FIVE SECONDS.

By the end of the first day, I was doing all my writing on a filigreed metal patio table just outside the offices, with only the constant traffic noise on Sunset Boulevard and the occasional homeless versus hooker debate to distract or inspire me.

It was a great spot. Every once in a while a voice actor who arrived early, or who arrived on time and was kept waiting, wandered out onto the patio to pass the time or to have a smoke. That’s how you end up talking to a Charlie Callas for 20 minutes about his early days drumming with Buddy Rich, for example. That’s how you hear a June Lockhart say something delightfully off-color, which I won’t repeat here because we’re still friendly and she comes to my block party every year. But it was about Jonathan Harris’s “acting.”

At some point, our showrunner discovered the building’s intercom system, which he then employed like Trump tweets to get the last word with everybody after unsettling meetings with individuals. My friend Larry Doyle was visiting me once when a booming, twangy voice came over the office-wide speaker system with an encouraging, “Anybody who doesn’t like working here can QUIT!” This is a good place to remember that he was there because the man he replaced was too hard to work with.

Of course, madness wasn’t the only thing driving the show. Pot was also a force. Because our offices were nowhere near the main Nickelodeon offices we were Colonel Kurtz Up the River; almost every day my boss and I started our workday by smoking a joint on his balcony. One of the show’s artists told me he used to get his pot delivered to the building by a dealer who would dress up in a full chicken restaurant deliveryman’s uniform complete with old-timey paper cap and aluminum hot case. The drugs inside the case were wrapped up and dispensed like food when he arrived at the lunch hour. (“Wowee-zowee, a three hundred and forty-three dollar ‘tip?!’ Thanks, mister!!”)

No one at Nickelodeon was ever aware of any pot use on the show, and as far as I know, at least while I was there, nobody ever tried to slip a drug reference or endorsement into an episode. We knew kids were watching along with the adults we were really aiming at. Still, the wary executives were always on the lookout for hidden content in our shows. Their assistant once wrangled a moment alone with me and nervously pointed to a word in a new script as he whispered, “Do you know what this means?”

The word was “spode,” but it definitely wasn’t being used in a way that had anything to do with scenic plate-ware, which I’m both proud and ashamed to say is the only meaning of the word that I knew. The s-word was cut from the script before I could learn what it was supposed to mean in that context, but I always assumed it had something to do with jizz. Again though, not drugs, Concerned Moms and Dads of America.

A lot of ideas suggested at R&S got shot down, including our showrunner’s notion that everyone in the office should wear a color-coded jumpsuit uniform, with layout artists in one color, storyboard artists in another, etc. He got the idea from watching either a Japanese cartoon or a movie about the future, I forget. I think the only support he got for this was from the sweet hippie girl assistant who wore overalls every day already. Artists and writers get into their professions to avoid uniform-wearing jobs like fast-food cashier, or Private First Class, which are basically the only other two jobs they may be qualified for, at least with more training. But as Frank Zappa once told a stunned audience of antimilitary hippies, “You’re all wearing a uniform.” And I prefer the uniform of the American male television writer, which is essentially the Michael Moore ensemble, minus the classy sport coat, and plus or minus three pant sizes.

Despite our lack of color coordination, there was a lot of collaboration on the show — sort of. When an episode turned out really good, three or four of the artists who worked on it would usually take a writing credit along with me. When an episode failed, they’d leave me hanging as the only writer. Which is fine; more $1.25 foreign-run residual checks for me.

One of the Ren & Stimpy episodes I wrote got me my first Emmy nomination, but we lost to a Shakespeare special that many on our staff complained was poorly written.

I did do some drawing on the show. When Stimpy created his own crude cartoon in one episode, my drawings were used as his. I drew it all haphazardly on 40 storyboard panels in a fast sitting, and the final was shot directly from those roughs. The whole idea of this was that Stimpy was the worst artist in the world, but somehow I’m still gratified I was asked to do it.

After about two seasons, I took a short hiatus from R&S to be a guest writer on Saturday Night Live, near the end of one of their seasons. It’s really a tryout for SNL’s next season, and I did it with a gifted writing partner, Charlie Rubin. But before SNL decided, we were offered a job writing for Seinfeld, and we snapped it up. I didn’t really have a desk to clear out when I left Ren & Stimpy, so before leaving I tidied up the patio a little.

By the mid-’90s, I was writing for The Simpsons, where I was not fired after many, many years, and where I had all the non-patio desk I could want. I never worked as an artist there, but I did supervise all the design work for a dozen years. While I was writing there, Matt Groening and David Cohen were struggling to find the right lead actor for their new series, Futurama, and I suggested R&S’s amazing Billy West—which got me a great Futurama show jacket that now hangs next to my great Ren & Stimpy and Simpsons show jackets in a closet I never use. I think the odd aroma in there is coming from my 23-year-old, lightly worn Seinfeld show sneakers, but I’m afraid to check.

I’ve never worked on a show where any of the actors remembered me after I left. When I worked in New York ages ago, I wrote pretty much every word a TV host said on the air for two years, and when I ran into him two years after that he had no idea who I was. I mean none. Or maybe without me he just had nothing to say. That was Bill Boggs, by the way, just so you know I’m not protecting his name today; in fact, I might be the only one getting it out there. So I was pretty gratified when I ran into Billy West several years after Ren & Stimpy and he recognized me from the show. He actually approached me. We talked for a while about the old Ren & Stimpy days and about who was doing what now. Then he said to me, “Hey, I heard one of the writers over there got hired at The Simpsons,” adding, “I think it was Ron Hauge.”