Last week, I wrote a piece about how—as a 35-year Publishing Guy—Substack seems to me an awful lot like…a publisher. So much of what they do are the exact same things that dead-tree media outfits have done for centuries that, IMHO, Substack should be held to the same cultural standards as “a publisher.” Hence, they should not publish Nazis, because since at least 1945 there’s been widespread cultural agreement that, while Nazi malarkey shouldn’t be banned (because censorship is bad), it also shouldn’t get the credibility and reach conferred by a mainstream, general-interest outfit. Especially one like Substack, which exuberantly and relentlessly embraces the publisher’s traditional role of disseminating information and taking a cut, but not the equally traditional role of vetting it and standing behind it.

Substack’s doing one but not the other isn’t high-minded principle; it’s simply brute commerce—dissemination is cheap and easy and can be done by machines, and moderation (what we used to call “editing”) is expensive because it must be done by people. Dissemination makes them money; moderation costs them money. But their desire to make maximum buck doesn’t give them a pass. Substack acts just like a mainstream, general-interest publisher when the content might hurt their bottom line (banning porn and sex work); but when it comes to Nazis, they trot out Silicon Valley’s bizarre, very much profit-driven version of free speech. And the typical sorts of people line up behind them, in the hopes that the Kings of the Platform will look upon them with favor.

Societies have endured new media for about 30 years now, and paid a terrible price for it. Dissemination without vetting has been sold as a weird kind of democracy, and if you’re too young to remember old media, I don’t blame you for believing it. But while we know one thing for sure—digital media is very efficient at what it is designed to do, make its owners rich—it is far from certain that the world of 2024 is freer, or better-informed, or more democratic than it was in 1994. Lots of evidence suggests that it is not. Why? Because there are lots of essential functions that quaint old things like local paper newspapers fulfilled, and digital media feels no need to address them, because it’s not really about “a marketplace of ideas”—it’s about making its founders rich. On the other hand, there is a lot more intelligent commentary about Steely Dan, a band I’ve always liked, so…it’s a wash? :-)

• • •

Anyway, lots of people had lots to say about my earlier piece, which was gratifying. I sincerely thank everyone who read it. Many people agreed with me, and some did not. A few claimed that I didn’t understand publishing and—after three decades writing, editing, and publishing books and magazines—I think I might be finally ready to agree with them. But what the “nays” really believed was that one shouldn’t suppress Nazis, but engage with them. Restricting their discourse would, in the words of Substack co-founder Hamish McKenzie, “make things worse”—though how, and for whom, was not noted. What boo-to-Nazis people like myself should do is address Nazi ideas, show their wrongheadedness and, if at all possible, drive them from the field via ridicule.

I consider this take to be disastrously ahistorical at best, and at worst actually dangerous. Germany from 1920-33 was a tremendously intellectual place, with the cultural and scientific accomplishments to prove it, and Germany’s Jews in particular were intellectually stellar. German scientists won at least one Nobel Prize a year from 1918 to 1933, including Albert Einstein in 1921. If reason and debate were really Nazism’s Kryptonite, Weimar Germany—lead by its Jewish thinkers—would have made short work of it. Instead, Nazism systematically hammered away at that society until—while still a minority thought buffoonish by sophisticates in Berlin and elsewhere—it was allowed into power by German elites frightened by Communism. And once in power, all “free speech” was done away with. Because Nazism doesn’t believe in free speech. It believes in violence.

But as someone who wrote short humor for many years, ridicule is my business. So yesterday I woke up from a dream with an idea for a piece. It was called, “A Short History of Nazi Germany.” What fun! Finally a use for all those Weimar books and Nazi documentaries I’ve consumed over the years.

The premise of the piece was simple: Far from being a bunch of hyper-violent, cynical opportunists spouting insane conspiracy theories and crackpot racial nonsense that got a lot of people killed, turns out the Nazis were really a sort of Bloomsbury Group in lederhosen, intensely self-critical, and more than willing to admit when they were wrong. Because that’s what they’d have to be, for Substack’s “sunlight theory” to work.

I had a great time. The more jokes I wrote, the more I thought of. I watched Ep1 of World At War and imagined Laurence Olivier delivering my punchlines.

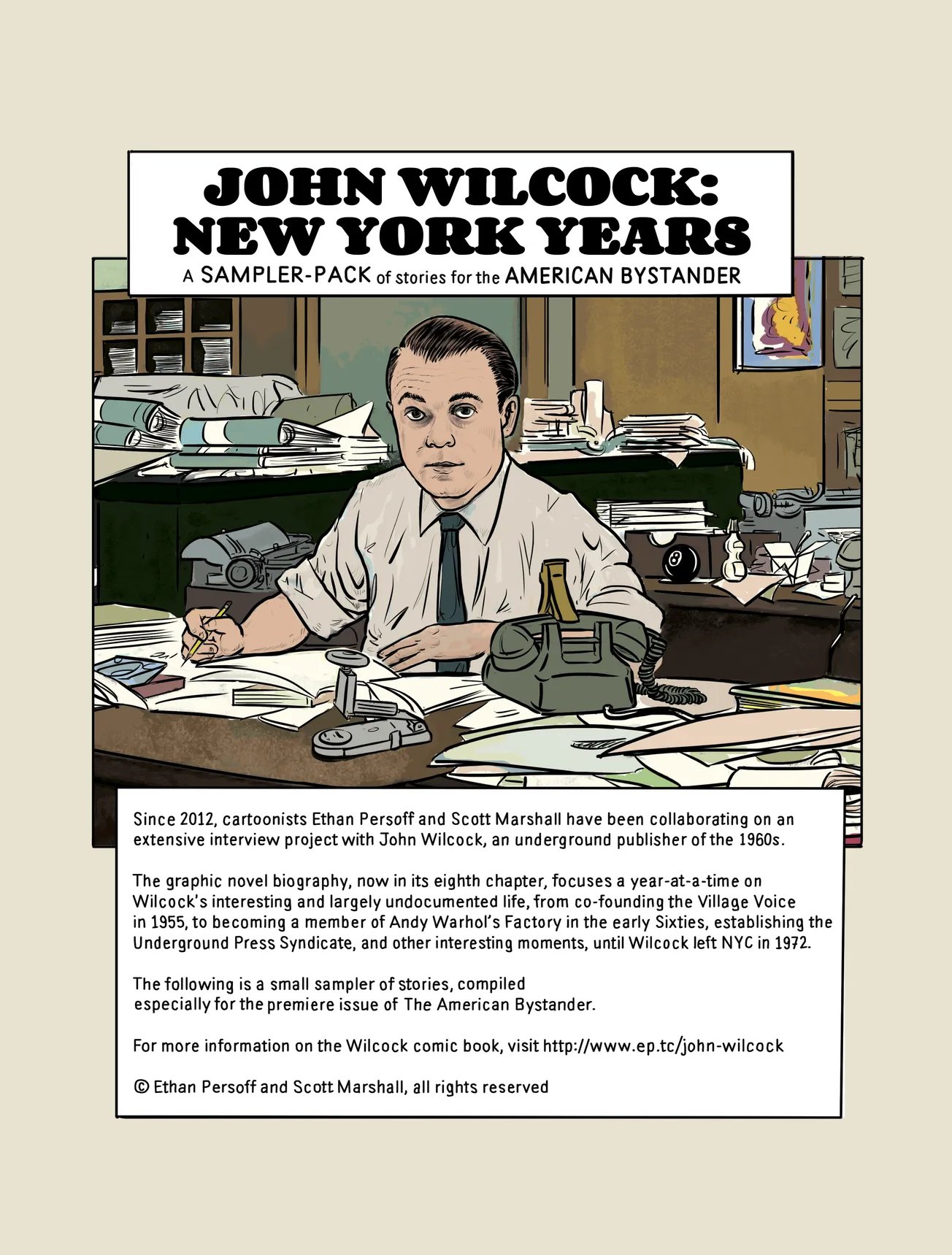

As I closed the file, I thought, “I wish the old Village Voice was around, they would’ve loved this. I wish there were any place to publish this.”

Why not publish it on Substack? For lots of reasons.

I. Who Is This For?

It’s almost impossible to write really great humor when you have no idea who’s going to be reading it. The very marrow of print comedy is predicting the audience’s reaction. If you don’t know who they are, you don’t know what they expect, what references you have in common, or what would surprise them. This blankness is particularly devastating to satire, because you run the risk of people taking your ironic points seriously, and coming away with exactly the opposite opinion. (“Thank God someone is finally standing up for the Nazis!”) When I wrote a piece for The New Yorker, the jokes were tuned to communicate to those readers, in that idiom; ditto, the NYT or WaPo or Village Voice or anybody. You must know an audience to communicate satirically to it.

Blasting out a piece to all and sundry is very bad for satire, and even pretty lousy for straight humor, unless it’s on truly universal topics (dating, parenting, food poisoning). But blasting out a piece is very very good—highly effective—if you’re selling unvetted, unfiltered junk designed to appeal to the limbic brain. Racial grievances. Conspiracy theories. Appeals to violence. Run those up the flagpole and if 0.01% salute, you have your own little Party.

II. A Few Words in Praise of Editors.

I’m deeply antiauthoritarian as a writer, so much so that I don’t even completely believe in grammar; Strunk and White can both kiss my ass. I have had more fights with editors than I can count, and I am the only author you know who threatened to return a $50,000 check to a publisher because I didn’t like the typefaces they were using on my book.

I am a handful.

But there are times when editors aren’t just useful, they are essential—and a satirical piece about Nazis is one of those times. A really experienced, really thoughtful, more than a little tight-assed editor is just what this piece needs, especially for the “Arbeit Mach Frei” joke.

III. The Comments.

Comment sections are the worst thing to happen to writers since the Income Tax.

For about fifteen years, I had a little hobby running the biggest Beatles fan site on the net. I spent an hour every day reading and moderating, and it was lovely. Trashed comments were vanishingly rare, and for about a decade, we had wonderful commenters; everybody learned a lot, and opinions changed as data was shared. Then, around 2015, something changed. Among all the good eggs, a new type of commenter started showing up, people with bizarre monomanias, indecipherable personal grudges, conspiracies, grievances…and those outliers attracted more of the same. I held out for as long as I could, but last year I had to shut the site down because of Gerber’s Law:

The quality of a media outlet eventually settles at the level of its worst commenters.

Commenters can actually wrest control of a publication’s (or “platform”’s) tone, and this is never to make it more humane, more nuanced, more intelligent, more respectful. It is to turn it into a vehicle for angry, obsessed people with too much time on their hands, or people whose job it is to move public opinion, often anonymously. Moderation is the only bulwark against this; and any publication (or “platform”) that eschews moderation reveals its goal as nothing as high-minded as a robust “marketplace of ideas,” but a mere data-shoveling business pumping up its bottom line so the founders can exit with Superyacht Money.

• • •

So if I polished up and published this anti-Nazi satirical fusillade—it’s in my drafts—in addition to making some people laugh, I would be signing up for at least a week of critique by idiots and assholes, people using my post to call me names, and rant about whatever bees are biting their brain. Just a torrent of abuse, and I’m not here for it. I’m too old and have too many better things to do.

This is a new problem facing our “marketplace of ideas,” and it’s not a small one. In addition to mere jokesters like me, we must admit that the people who have the most interesting, most insightful things to say—things we need to hear—are not always or even often the people with the thickest skin, and almost never people who want to spend all day every day fighting online. Every writer I know who has successfully made the transition from Old to New Media has been psychologically damaged by that transition, either via addiction to social media, hours wasted “engaging” with churlish strangers over nonsense, or a peculiar flattening of opinion based on the possibility of getting dogpiled. We’ve created a world where not only do writers have to put up with the traditional Four Horsemen of The Writer’s Life—Poverty, Obscurity, Self-Doubt, and How Hard It Is to Write Even One Good Sentence—we now also have to put up with a Fifth: abuse. From strangers. Who are crazy.

Which feels a little different when you don’t own the platform. No Nazi is going to really inconvenience Hamish McKenzie or any of the other owners of Substack, at least as long as they’re allowed posting privileges. Nazis can be very polite, if they think you’re in charge. But the rest of us cannot expect similar courtesy.

So maybe Substack and all the places like it aren’t “publishers”—maybe they’re something much, much worse. Something that doesn’t help writers or intellectual debate, but narrows and coarsens it, and makes creative people have to look over their shoulder—not for a critic, but for a faceless, pseudonymous hater who has nothing to lose and everything to gain by being terrible to you.

When I read my piece to my wife, she didn’t smile.

“Not funny?” I asked.

“Oh it’s funny. But some people won’t get it, and others will pretend not to, and everybody with an axe to grind is going to call you names. Is this how you want to start the New Year?”

No, my dear friends, it is not. To all: I wish you every blessing—Happy 2024.