I’ve been having trouble eating, again. Ever since I got back from New Haven nine weeks ago, my appetite has been gone. Every morning, I make myself choke down a chocolate bar, because that’s all I can stomach. Some days that leads to other things, most days, it doesn’t. I’ve lost about 15 pounds so far, which is okay; for the past several years, I’ve been meticulously crafting a hoped-for persona as the Fat ‘n’ Happy Carb-Powered Sicilian. So I had the pounds to lose, and I love all the once-tight clothes I can wear, but…there’s that cold breath on my neck, again.

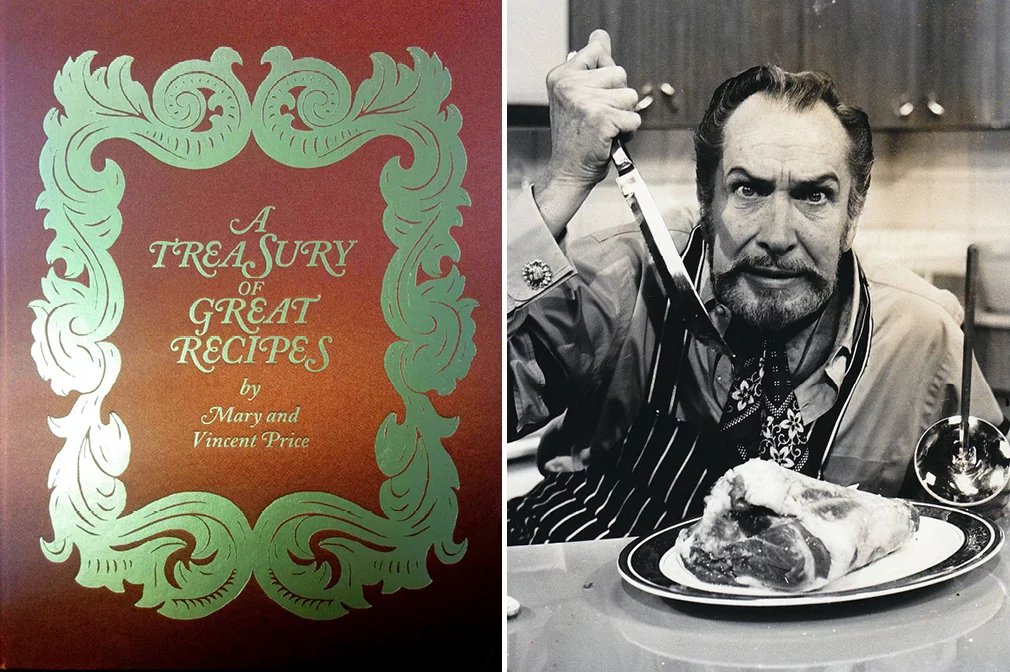

However, things may be looking up. This past Tuesday, after a strong qigong session that ladled qi all over my aching joints, I had a craving for a dish that I haven’t made for almost a year. It’s a tomato-y chicken curry recipe, cribbed by actor/archgourmet Vincent Price from the chef at the Hotel Pierre in Manhattan. You can find it on page 142 of A Treasury of Great Recipes, a cookbook/timecapsule so fascinating there’s an actual YouTuber who makes the dishes online. Wanna cook “Raw Meat Lucullus” from Lüchow’s? Of course you do. And the picture of Price eating a Dodger Dog is itself worth the price of admission.

My well-used copy is rapidly returning to its constituent molecules, which means it’s time for a trip to ABE for a replacement. (It was reissued in 2015, but I have an attachment to the original.) There are a few books in my rapidly shrinking personal library that mean an awful lot to me—Robert Graves’ I, Claudius; The 1964 High School Yearbook Parody—but of them all, A Treasury of Great Recipes is my only must-own. Here’s why.

In February of 1991, I was crouched on the launchpad, onfidence, ambition (and arrogance) billowing off me like water vapor on a cold Cape Kennedy morning. After twenty years of preflight, I was ready to hurl myself into the stars—maybe start a magazine, maybe a lot more.

Then I got the flu.

I didn’t think anything of it; why would I? Yale College is Nature’s perfect petri dish. Everyone’s overworked, living on top of each other, and the weather…well, the weather truly sucks. New Haven’s roughest break not named “Yale” is being northerly enough to get cold, but positioned on the water, so that all that sleet never ripens into snow. Around November a damp chill sets in, and it stays ’til late March, crouching in your bones. People react to this by working too hard, huddling together (ahem), and doing a fair bit of drinking. From Halloween to (Kentucky) Derby Day, everybody on campus is a little bit sick.

So as a Senior, I expected it. But unlike every other sniffly ache, this one didn’t go away. After my immune system would pound it back into its hole, this illness sprang up again and again, like guerrillas emerging from the jungle at night to kill traitors and burn crops. Confidently. Defiantly. Terrifyingly certain of its success.

One night over cigars, my girlfriend’s father noticed my month-old cough. “You still haven’t kicked that?” he asked. “I’ve got just the thing.”

“More cigars?”

“So you’re the one who’s been stealing them.” Of course I had been, and we both knew it.

Smiling, Duncan disappeared upstairs, then returned a minute later with a foil packet. “I got tummy troubles in Mexico, and only took half.”

I popped a pill through the foil, then examined the package. “What’s ‘Cipro’?”

“Oh come on, man, don’t be a ninny. Are you tired of coughing or not?”

Not wanting to contradict the father of a girl I was crazy about—who was a Yale professor besides—I took the pill, gulping it down with a swig of brandy. I took the rest over the next week.

On such small stupidities a life turns. Between the flu and the antibiotics, I apparently devastated what doctors now call “the microbiome,” the vast and teeming billions that do everything from chase your blues to digest your brandy. Ever after, my immune system was stuck on high, prodding me into a constant, smoldering state of food poisoning.

Within a month, my body smell had changed; within two, I’d lost 50% of my eyebrows. This, to a man as vain as I, was a particularly cruel blow—but things had just gotten started. The week after graduation, home for a brief visit before establishing a beachhead in Manhattan, my mother grabbed me. “What did that shitty college barber do to your hair?” she demanded. “It’s so thin.”

By Halloween, I’d become violently reactive to the smallest speck of dairy. By New Year’s, I couldn’t digest wheat, either. And then the doctors’ visits began: expensive, time-consuming, eventually dispiriting, too, because nobody could tell me anything. Most of them thought it was all in my mind.

“Gelusil?” one doctor suggested the month I became housebound. “Or maybe apply for Disability?”

By 25, I was no longer a rocket aimed at the stars, but functionally a recluse. Career gone, girlfriend gone, I’d gotten a cat. Whenever I ate—whatever I ate—what happened next was totally unpredictable, often painful, and utterly embarrassing.

“Maybe try biofeedback?” another doctor said. “It might help with the anxiety.”

New foods were added to the verboten list almost daily. Wheat, dairy, nuts, spices, colorings, additives—some days I couldn’t even drink water. Something that digested fine yesterday could cause a reaction tomorrow. I’d make a wrong guess, and be laid up for a day as my system calmed down. And as I grew older, the reactions grew stronger, and lasted longer.

At the age when most people are pursuing careers and love, I was investigating putting a port in my stomach. Pros: an elemental diet—simple aminos and such—would keep me alive, and be less likely to cause a reaction. Cons: constant risk of infection, expense, there’s a goddamn port in your stomach.

I couldn’t keep a job, so I stayed at home with my beloved cat, and wrote; somehow I always managed to write. Barry Trotter happened in the middle of all this, if you can believe it. (By the way, my Parody Master Class is going great.) I would’ve died for sure, had I not found and finagled into matrimony my dear wife Kate, whose commitment to my care was—and remains—total.

Even so, by the time I was 42, nothing worked anymore. Scarily pale, hollow-eyed, I was 119 pounds—a full 55 pounds lighter than this past April. I was living, existing really, on four things: beef, potatoes, lactose-free ice cream and—when things got bad and I couldn’t eat anything else—the chicken curry recipe my mom used to make when I was a kid. My birthday dinner was keeping me alive.

Of course I will share the recipe. That’s why I’m telling you all this.

Remove the meat from: 2 tender frying chickens, each about 2.5 pounds (or use 5 pounds of chicken parts). A boning knife is a big help in cutting the raw meat from the bones, and you might ask your butcher to order the proper kind for you. Remove the chicken skin and cut meat into bite-sized pieces. The skin, bones, necks, backs, and wings may be used to make chicken stock.

CURRY

- In a heavy saucepan heat: 1/2 cup cooking oil or butter.

- Add: 4 cloves garlic, chopped, 4 medium onions, chopped, and sauté for 5 minutes, or until vegetables are golden.

- Add: 2 whole canned tomatoes, chopped, 1 bay leaf, 1 teaspoon cinnamon, and 6 cloves. Cover and cook for 5 minutes. [I use a full can of diced tomatoes, because there’s more gravy that way.—MG]

- Add the chicken meat and cook over high heat for 10 minutes, shaking pan occasionally, until most of the liquid in pan has steamed off. Reduce heat.

- Add: 2 teaspoons salt, 2 tablespoons curry powder, 1 teaspoon pepper, 1 teaspoon cumin, 1 teaspoon coriander, and 1 tablespoon paprika. Stir to mix the spices with the chicken meat, being careful not to let the spices burn.

- Add: 3 to 4 cups water, or enough to cover chicken meat. Bring to a boil and simmer for 35 minutes.

- Before serving add: 1/2 cup fresh coconut milk and heat gently.

So this, according to dear Vince, is the handiwork of “Reaj Ali, the Moslem chef of the Pierre’s East Indian kitchen.” Make it and you will not be disappointed; Allah was truly guiding Ali’s hand here. By the way, New York City’s Hotel Pierre is still around today, and the only thing Richard Nixon and John Lennon both loved.

When he wasn’t skulking around fake dungeons wearing makeup, my fellow St. Louisan and Yale Record alum Vincent Price was collecting art and going to fine restaurants. All of this sort of fits; there was a decadence to his menace, conventional masculinity’s warning that this was where too much sensitivity would get you. (Twenty years later, Hannibal Lecter would update this idea with his “fava beans and a nice Chianti.”) When I was a kid, you could totally see Vincent Price murdering someone gruesomely, diabolically, and getting away with it. And then living out his days, ignoring the whispers, eating Reaj Ali’s curry in the penthouse of the Pierre.

We mustn’t judge him, you and I. We don’t know how hard his life has been. Maybe he got the flu.

When A Treasury of Great Recipes was published, the Pierre stood for a certain kind of sophistication, a certain kind of luxury — which was what I suspect my mom was going for when she attempted to make chicken curry for the first time. Her mother “cooked out of cans,” and Mom was determined to do better. While I was five and would eat anything, Mom was 24 and trying to impress a boyfriend — as well as introduce me. Mom was raising me herself, and this dinner was meant to express that the lucky winner of the sweepstakes would indeed get all the comforts of home…but that she and I we were a package deal.

That boyfriend didn’t last. The chicken curry did.

I don’t know what it was about the curry that my failing body craved—was it the turmeric? The ginger? Did it give me a vitamin I needed? Kill a little one-celled gangster muscling in on some vacated GI territory?

Or was it simple comfort, a return to childhood, a time when my digestive system could be trusted, and the stars my destination? Reaj Ali’s chicken curry creates a powerful incense—the spices, the chicken and tomato, and onion. The first time I cooked it for her, my Indian sister-in-law walked in and said, “It smells like home.” For me, too.

I never figured out why it worked, but I’m so so glad it did. Many days, I’d spend the last flickers of my vital force chopping onions and garlic, browning them in an electric skillet, stirring in tomatoes and chicken. Then, I’d rest on the sofa, cat on lap, as the dish cooked down. In an hour, the smell would give me strength, and I’d fill a plate. I’d eat like a lumberjack, maybe the only time that week. And I’d learned to dine directly before bed—the better to keep on the weight. Then I’d polish off the rest the next day for breakfast.

What cured me? Well, that’s another, even stranger story for another time. But as I grew well, I lost my taste for Reaj Ali’s chicken curry. It’s still delicious, but I almost never make it now, much to my wife’s dismay. For me, apparently, it was medicine, and—as I learned—the wrong kind at the wrong time can cause true horrors. It’s nice to know that it’s there for me if I need it.

Salvation comes in strange packages. And sometimes with coconut milk.◊