I love Pride Month. In part because it’s my birthday month—I share a birthday with Boy George, tennis player Steffi Graf, and a certain former President soon-to-be-jailbird (we fervently pray). But also: how could anyone not like Pride? Born in strife it might’ve been, now it’s a party—thrown by a bunch of people who really know how to party—celebrating love and sex and people expressing them own weird selves. Three things which, c’mon, if you can’t get behind that, it’s a you problem.

I grew up in St. Louis’ gay neighborhood, the Central West End, in the pre-AIDS halcyon days. Back then, in the 1970s, people weren’t just gay, they were GAY. GAAAAAAY. Compared to the the rest of St. Louis, or God forbid the suburbs, the Central West End was simply another planet, co-ruled by our benevolent dictators Sylvester and Fran Lebowitz.

Living there was just about the nicest thing anybody ever did for me, and as soon as my boilers built up enough adult steam, I sought out more neighborhoods just like it—first Capitol Hill in Seattle (as I’ve written here), and then New York’s West Village. I still dream about my tiny garret on West Eleventh between Bleecker and West Fourth; when I lived there in the late 90’s, the neighborhood was in this weird platypus phase between its days as the Gay ghetto (that’s Chelsea now I gather?) and what it is today, a sort of boutique version of New York occupied by billionaires. The Paris Commune for Sunday brunch, late nights at The Corner Bistro, nodding to the gents through the doorway of the Boots ‘n’ Saddle.

Where I live now isn’t gay ground zero (that would be West Hollywood), but Santa Monica is definitely gay-friendly. David Hockney and Christopher Isherwood used to live here, and a million Industry folks still do.

I’m a straight white cis male, but I’m also disabled, so I’ve had to make up my own version of—and make my own peace with—masculinity. How do you even do maleness without being bigger than, stronger than, or able to pass the thousand tests of physical endurance and aptitude that are built into American manhood? When my younger brother was in high school, my Dad would lay in wait for him in the kitchen, and they would wrestle whenever Jack got home. Until one day Jack tired of the game, and tweaked my Dad’s rotator cuff so hard the ambushes stopped.

Like it or not, that could never be my tribe. When I was a boy, I looked at the queer people around me and saw them grappling in their own way. So they’ve always felt like my type of folks, and I’ve always tried to reciprocate, even though I’m sure I’ve failed in that many, many, MANY times.

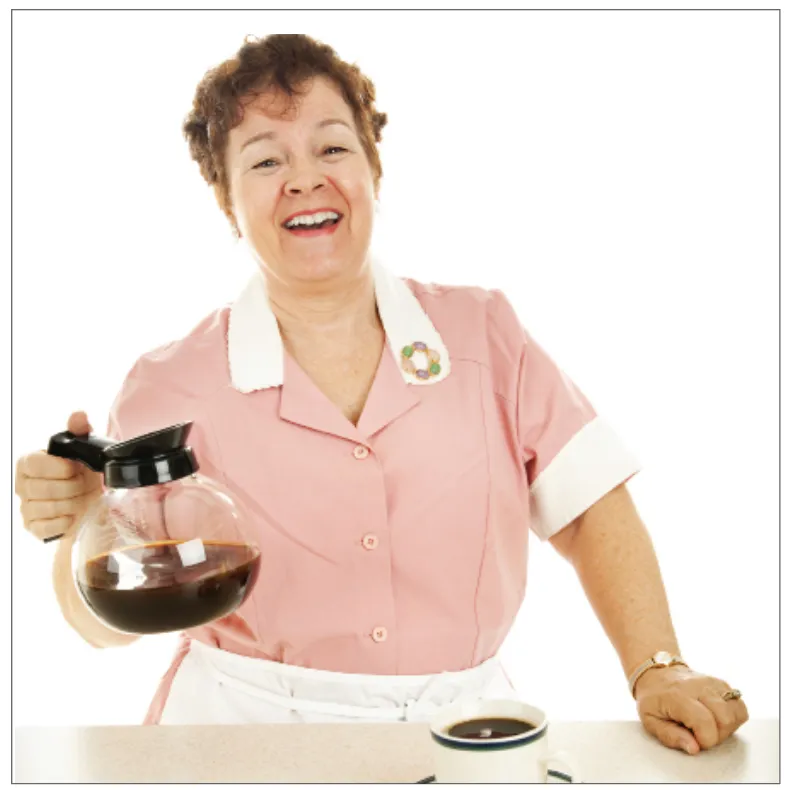

When I was a little boy, being raised by a gaggle of young women, college students where my mom was going to art school, and waitresses and patrons at the bars where she waited tables, most men felt…unsafe. Definitely untrustworthy. Prone to anger. These guys—usually total strangers—frequently had an opinion about how I was doing boyhood. My haircut, my speech, how I was dressed, that I was there with them at all. “Shouldn’t you be outside,” they’d say, exhaling breath strong enough to stun a weaker six-year-old, “playing baseball or something?” I learned to read their manners and posture, their expressions and clothing, even their smell. (Drunks have a particular sweet smell; I think it’s their livers not processing the alcohol.) Most of these nasty men, I avoided; and all of them, it turned out, were straight.

Some men I met were not straight—which was explained to me simply as, “So-and-so has a boyfriend instead of a girlfriend,” information that did not melt my developing brain. Some of these gay men were kind; some were just quiet; none were menacing. I am sure that there were gay men in Llywellyns and O’Connells who hated kids, or just didn’t like me, but I don’t recall any. And so I’ve always had a special affection.

In high school, I discovered I had an affinity for lesbians as well. Once or twice I’d find a young woman I could talk to somewhat more honestly and clearly than usual—because, it turned out, of a total and complete absence of sexual attraction on her part—which would make me feel attached and bonded and friendly towards her. Sooner or later we’d have to have “the talk,” and that would be a bit painful, but I’d get over it—I had become infatuated because we were friends, which seemed like a good policy. Then in college, I got to know a lesbian couple in their late twenties, whom I adored. Nanci taught me a lot about women, our mutual fascination.

So it was natural that I would head to the gay ghetto whenever I moved to a new town. And I—though straight-aware from the age of four—not only felt welcome there, but welcomed there. I’ve always tried to give that same feeling back, whether it was saluting a gentleman in his Tom of Finland peaked leather cap and harness—he was so proud of the look, striding out of Condomania on Broadway in Seattle, nipple rings glinting in the sun—or my encounter with the showgirl, who I think of every year around this time.

It was just before midnight on Sunday, the tail end of Pride Weekend 1996. I was sitting on the stoop of 266 West Eleventh, as I often did late at night. I’d write all day, seven days a week, desperately trying to build my talent and bank account before the roof caved in; then about eleven, I’d knock off, and plant my butt on the gritty standstone steps downstairs, relaxing in the cool, letting my brain spin down. Sometimes, if I had something to celebrate, I’d even smoke a cigar. Good health is wasted on—and by—the young.

The parade had taken place earlier that day, four blocks over on Christopher, and the neighborhood was littered with little glossy flyers promoting various parties—some of which were still going strong all around me. I heard music from the Cubby Hole around the corner, but there was also Henrietta Hudson’s, the Boots and Saddle, TJ’s, Fedora Bar…the neighborhood was full of parties. I watched people walk from these, arm-in-arm or very much alone, some unsteady, some exultant, some sad or mad or tired, and everybody on their way to the subway, back home, back to their real life, back to the week ahead.

Just before midnight, as I my butt grew numb and I thought about going to bed, I saw someone turn the corner off Bleecker and walk toward me. It was…a showgirl? Like, Vegas-style, and the whole nine: thigh-cut sequined bodysuit, full eye makeup with long false eyelashes, and a feathered headdress at least two feet tall. This was commitment, and I admired her for it. (I’m going to use the female pronoun because that’s what she used at the time.)

As she drew closer, I noticed she was limping. “Ay, coño!” Her strappy platforms were to blame.

“Nice night,” I said, puffing on my cigar. I’d gotten paid that weekend for a piece in The Atlantic, so I’d broken out a Cuban, a strong black Bolivar I smuggled back from Mexico.

“Hi,” she said, in a voice a bit deeper than I expected—she was tiny, not even five feet without the platforms and the headdress. She pulled out a cigarette tucked in her bra. “Got a light?”

I handed over my Zippo. (I still have that stinky old thing somewhere; I liked carrying it, but there’s no point if you don’t smoke.)

“Thank you. Mind if I sit?”

“Please—I can’t imagine taking a step in those things.”

Sitting on the rough stoop, she unhooked a shoe and rubbed her foot. I never learned much Spanish, but her expression said it all.

“How long have you been on your feet?”

“All day,” she said. “Made good tips, though.”

I gave a thumbs up. “You don’t mind the cigar?”

“No, I think it’s very…butch.” She laughed and I did too. “You live here?”

“Yeah,” I said. “Me and my cat. Sorry, not very butch.”

She laughed. “What’s your cat’s name?”

“Fifi.”

“Oh, she’s a showgirl, too.” The other foot came out, slowly, tenderly. “Look at that blister. I’d take them off, but I’d ruin my hose walking to the subway.”

“Let me run upstairs and get you a Band-Aid.”

“Listen, papi”—she put her hand on my foot—“no funny business, but could I come up and use the ladies’? I have a long ride home.”

“Of course,” I said, smiling.

“What’s so funny?”

“‘Funny business.’”

“Oh, it happens. Especially today. And the straight-seeming ones are the worst.”

She saw me get up, slowly; my always-stiff legs were nearly asleep from sitting.

“Your feet hurt, too?”

“Sort of.” I turned and unlocked the front door, then the inner door, then we climbed the stairs.

“Is your place nice?”

“Not really,” I said, “but it’s small. I’m here for the neighborhood.”

“Me too.”

My door was at the end of a short hallway, and opened right against another door opposite, in the way of too-cramped, over-divided New York apartments. As I dug out my keys, the showgirl heard Fifi’s meow.

“I hear your kitty!” I opened my door, and Fifi was there to greet me, as she always was.

The showgirl knelt down. “Oh Fifi!” she said gently. “Hello little girl.”

“The bathroom’s right in here,” I said, pointing to the corner of the kitchen.

“I’ll try not to get lost,” the showgirl teased. “Thank you.” Fifi and I walked ten feet away to the far end of the apartment, to give our guest some privacy. Presently I heard the toilet flush then the water run.

“Oh, Papi, you have no idea how much I needed that,” she said.

“Would you like a glass of water or something?”

“Dios mio, no,” she said. “I’ve already had plenty to drink.” She’d taken off her hose, which peeped out of her small bangled clutch. Then she sat down on my cheap leather footstool. Fifi, black and fluffy, wound herself around the showgirl’s legs as she put on one shoe.

“Oh, one sec.” I rummaged in a junk drawer, hoping the Band Aids my mom had left after her last visit were there—my bachelor pad had a humidor but no medical supplies. “Found it!”

“My knight in shining armor.” Crossing her now-pale ankle across her knee, she applied the plastic strip carefully around her heel.

“It’s antibacterial,” I said.

“It’s perfect.” The showgirl gingerly slid her shoe over the bandaged heel, then stood. “Good enough to get me home,” she said.

Walking her the three steps to my door, I saw a little silver sequin on the knobbly black kitchen tile. “You dropped this.”

“Keep it,” she smiled, then: “Thank you, Papi, for the Band Aid.”

“And no funny business,” I teased.

“I wasn’t really worried,” the showgirl said. “I could tell, you’re a real gentleman.” Then, before I could respond, she leaned over and kissed me lightly on the cheek.

My showgirl was out the door before I could even stop blushing.

“Happy Pride,” I called down the hall.

“Happy Pride, Papi,” she trilled back. I watched her turn and walk down the stairs, her headdress disappearing from view.

“Youse be QUIET!” yelled my neighbor Norman. Norman was always angry.

“Be quiet yourself, ASSHOLE!” my showgirl said, letting her voice slide low on the last word.

I laughed, and from the first floor below, I heard my showgirl laugh too. And then she was gone.