Suddenly, the entire internet is asking: “How often do men think about the Roman Empire?”

I have been waiting for this question, waiting since 1976, when my mom and I watched I, Claudius on PBS. It was only natural I be fascinated with that show; it was already my habit to look to history to figure out how to be, and as a seven-year-old with cerebral palsy, Claudius was pretty much the only historical figure who fit my requirements. Eventually this led to five years of Latin, which I never quite got. Then a smattering of Roman History at Yale, taught by the legendary Ramsay MacMullen—assisted by, if memory serves, a TA who looked like Jerry Lewis. This TA also wore a bow tie which, at the Yale of 1989, signaled the wearer was at least conservative-curious. Think hankie-code by way of George Will.

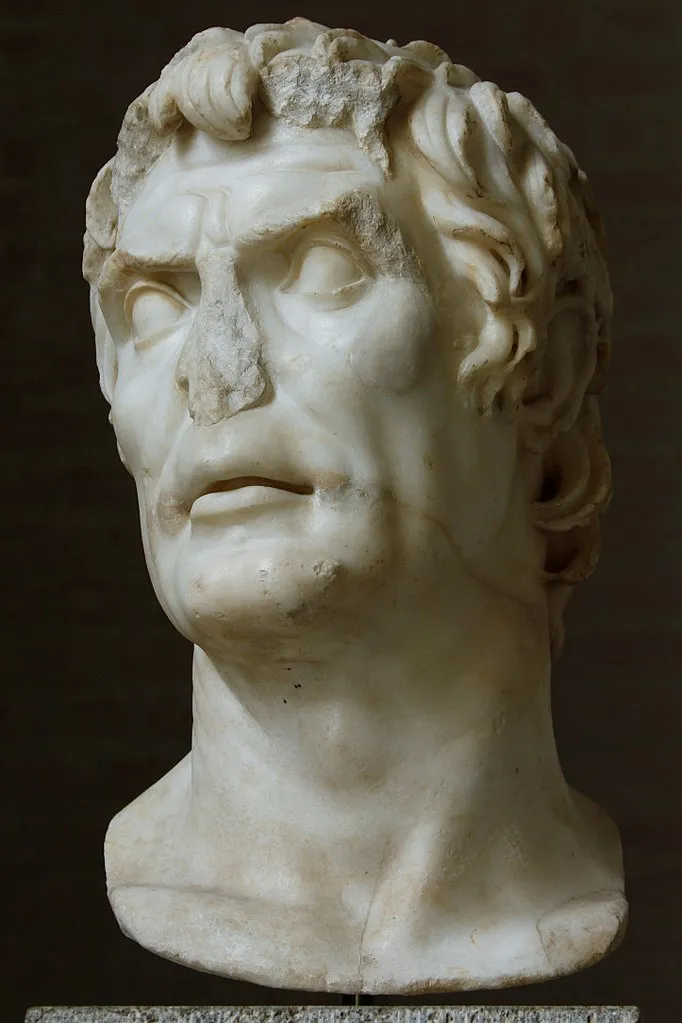

Ancient Rome attracts conservatives. It is perceived to be more manly, more authoritarian, more martial, and less sexually suspect than Greece, less “artistic.” And it’s one of the few areas of history where the old historians haven’t really been swept away entirely; you’re as likely to hear a quote from Edward Gibbon as Mary Beard. For centuries, the story of Rome was written by English and German aristocrats reading Roman aristocrats and taking their word for it. Even today, the general person’s idea of “Rome” has as much to do with Victorian England and the playing fields of Eton, than what life actually might’ve been like on the Italian peninsula two millennia ago.

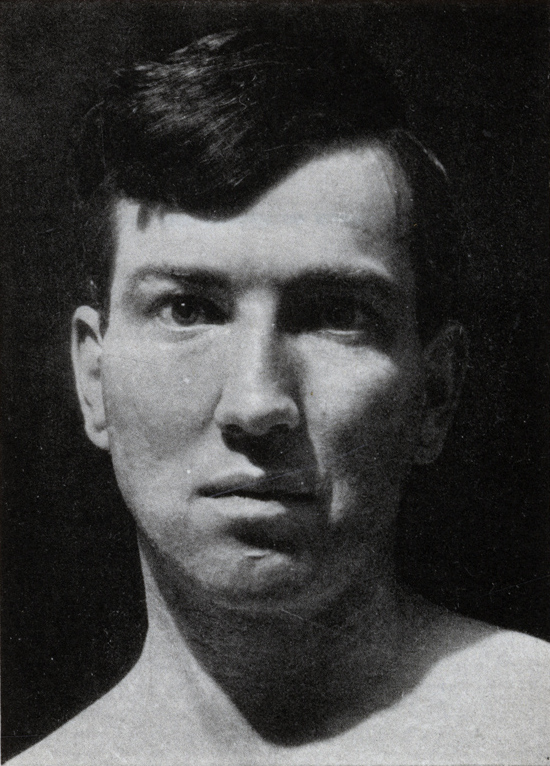

Add to this the regrettable Confederate obsession with Rome. It would’ve been a one-sided love affair—John Wilkes Booth, for example, perfectly encapsulates two things Romans despised: people who lost, and actors. For all the high-sounding rhetoric, it was the unfairness of Roman society that made Southerners see themselves striding the Forum. There is a thrill to it; using the word “liberty” to keep other people in their place—to a certain type of asshole, that’s indescribably delicious. You read it in ancient Roman texts, and in Confederate writing, and on the internet today.

• • •

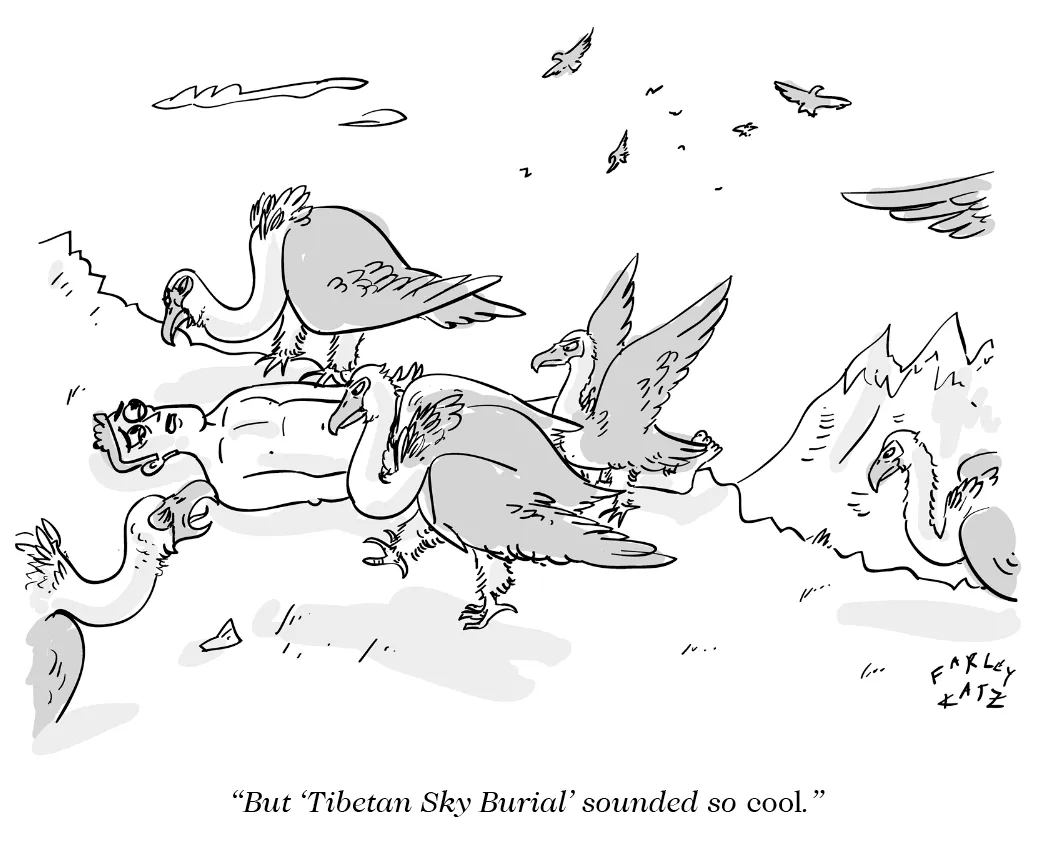

Of course what this question really means is, “Men: how often do you think about movies and TV about ancient Rome? Specifically that scene in HBO’s ROME where Atia of the Julii emergeth from her bath?”

Beautiful naked women with exotically trimmed pubic hair, unlimited buffets, fantasies of single combat—is anybody surprised men think about this a lot? And then there’s the Fascism-lite brigade, who say things like, “Men, to our core, I think are warriors. You have to be ready for battle at all times, and the Roman Empire is all about battle. Common sense!” This from a guy who doubtless prepares for “battle” when Instacart delivers the wrong Chobani.

Once upon a time, goes the myth, there was a society where everything made sense. Where the right people were always in charge. Where everybody else knew their place, the old values were respected, and rural life was cool. And then, because people became immoral, because they became decadent, because they lived in cities and the wrong types were given too much—because nobody wanted to work—it all collapsed.

Of course modern conservatives love this myth; it was created by Roman conservatives 2,000 years ago, when their society was facing troubles similar to our own. Their solutions didn’t work, but the problems are so similar to ours—wealth inequality, diversity and inclusion, the limits of military power—that ancient Rome actually is quite useful to think about today, just not in the ways conservatives frame the discussion.

• • •

The first thing I would say is: quit thinking about the Roman Empire, and start thinking about the Roman Republic, specifically the late Republic. The Imperial period—which extends from the ascension of Octavian in 31 B.C.E., and ends roughly with the sack of Rome in 410 AD (and yeah, I didn’t have to look up either of those dates, thanks Prof. MacMullen)—has a lot fewer concordances with our current era than the period of the late Republic, spanning from the death of Tiberius Gracchus in 133 B.C.E. to either the death of Caesar, or Octavian’s victory over Mark Antony at Actium.

Republican Romans of the aristocratic class were outwardly pious, but ruthlessly competitive and relentlessly materialistic. They were nationalistic only to the degree it benefitted them personally, and terrifically xenophobic because military adventure and conquest made them money. Their idea of “liberty” was basically “let me get as rich as possible.” They professed to despise kings, but as Octavian proved, turned out to be perfectly fine with being ruled, as long as there was a clear hierarchy, they received sufficient goodies, and somebody else had it worse.

Republican Rome was an oligarchy masquerading as a republic; while voting was possible for many, both the structure of elections and the money necessary for public office meant that all meaningful decisions were made by a small group of impossibly wealthy citizens. The Senate—and really most of society—was dominated by a group of interconnected families, and any person who was able to break in (called a novus homo or “new man”) could only do so by servicing the interest of those families, and mouthing their prejudices. If reform was ever going to come, it would have to be from enlightened aristocrats, people at the top of the heap. And eventually, that’s what happened.

The late Republican period was characterized by an increasingly violent clash between two factions, the Optimates (“best men”) and the Populares (“party of the People”). Though it’s always important to remember that both parties were run by the superrich, the Populares believed that it was time to share the wealth Rome had acquired over a couple of centuries of conquest, and be looser granting Roman citizenship. They did not do this out of kindness, but because they felt society was growing dangerously unstable.

The Optimates disagreed, were absolutely opposed to sharing any land or privileges, and felt that by accruing ever-more wealth and power, they would remain safe. That was how it had been done in the past, and that was how it was going to be forever.

The Populares cause was both sensible and just, and so gained more and more traction. But any moment it seemed the balance of power might change, the Optimate faction would declare the Populares leader a demagogue and “enemy of the People,” and arrange for him to be killed, sometimes by hired mob, and sometimes by a mysterious assassin who nobody ever caught.

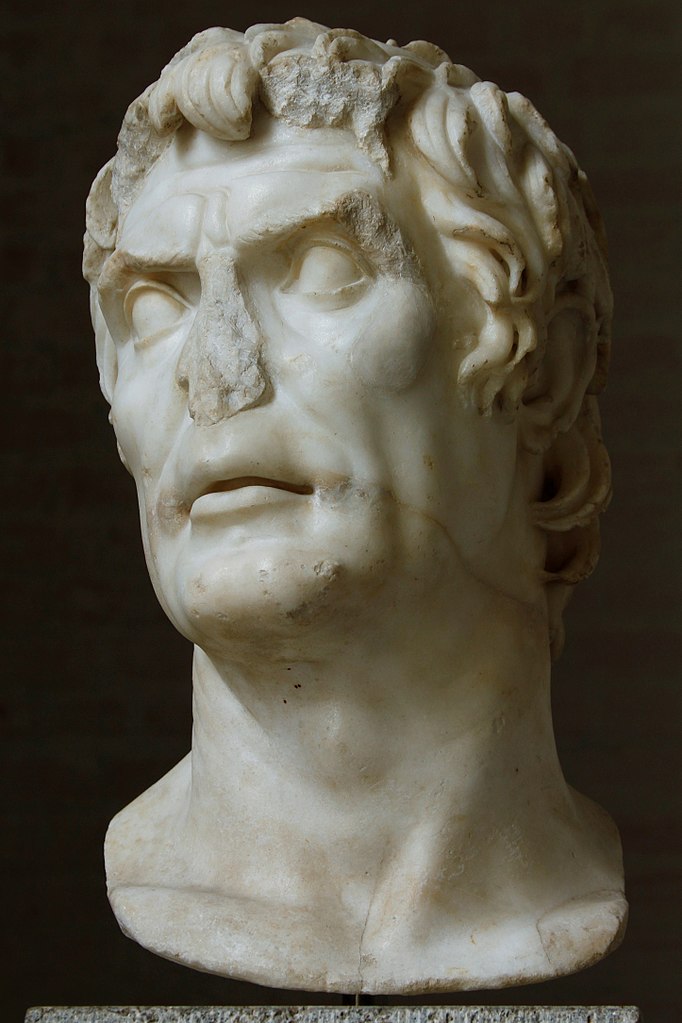

Eventually killing leaders wasn’t enough, so the Optimates rallied behind a disgruntled but talented commander named Sulla, who was the first Roman general to march on Rome. After he installed himself as Dictator, he passed a bunch of legislation designed to “make Rome great again,” and basically freeze things like how they were before everybody got uppity.

Whatever lousy stuff you were told about Julius Caesar (Populares), goes double for Sulla (Optimate); Sulla was vindictive, vain, arrogant, and wanted to rule Rome like a King. But it was okay because he was a conservative—though there was nothing conservative about what he did. Optimates habitually broke the heaviest “norms” in Roman society—don’t kill a Tribune, don’t bring your soldiers inside the sacred boundaries of the city—and got away with it, whereas Populares leaders were murdered for the silliest reasons (for Ti. Gracchus, he might’ve gestured towards his head like he was asking for a crown; for Caesar 90 years later, he didn’t decline the crown fast enough).

Gaius Julius Caesar is one of my obsessions and much, much too big a topic to get into here. But there are two things that are germane to this 30,000-foot view I’m giving you. By the time he was born in 100 B.C.E., Rome was producing warlords. To reach the highest level of Roman politics, you had to either be an actual general—with soldiers under your command or loyal veterans settled in strategic parts of the boot—or you had to be so fantastically wealthy you could buy an army at a moment’s notice. It was a time of ever-greater fortunes enabled by governmental access and self-dealing, which produced ever-larger armies more loyal to their paymaster commander than to Rome.

Caesar’s “crossing the Rubicon” was not, if you’ll forgive the vulgarity, the Republic having its cherry popped, with Imperial Rome sure to follow. That deed had been done decades before, by Sulla. Caesar was chilling in Gaul with his armies when the Optimates in the Senate demanded he leave his army and return to Rome to face trial over supposed improprieties. In late Republican Rome, trials were usually not attempts to get at the truth, but thoroughly political operations designed to weaken one’s enemies. Caesar may or may not have been guilty of these improprieties—he habitually did exactly as he pleased, and made up the reason later—but it was a certainty that if he gave up his army, he’d either end up exiled, or simply murdered. When he crossed that stream in the North of Italy, Caesar may or may not have been intent on one man rule, but he was certainly protecting his own life. I personally suspect that he wanted to set up some Duovirate with Pompey, his fellow general, main rival and former son-in-law. Caesar was arrogant and ambitious, but he was also smart, and knew that while a Optimate Dictator like Sulla might survive, a Populares Dictator seated in Rome would not. It would cause endless flip-out from the Optimates, who had made hatred of people like Caesar—not any kind of governance—their whole reason for existence.

• • •

History does not repeat, but it does rhyme, and it’s impossible to know all this stuff and not think of it constantly as you read today’s news. I think we’re deep into the warlord phase; if you don’t believe me, consider Elon Musk’s activities with Starlink in Ukraine. Our political system is suddenly having a great deal of trouble defining clear boundaries of power and controlling oligarchs, and one side—the supposed “conservatives”—see the empowered oligarch as the only way to 1) grow their fortunes and 2) restrict immigration. It’s land and citizenship, all over again.

It’s comforting to think of the contemporary United States as the heir to the Roman Empire, a period were most average citizens were unbothered by politics, traveled widely, had generally good diets and material comforts, and so forth. But before the Empire, there were the Civil Wars, bloody, gloomy, ever-shifting conflicts where powerful personalities grew larger than the surrounding state. At that point, conflict became inevitable; it was in fact, necessary to see which warlord would come out on top. I think for us this sad process began in the 1960s, where reformers working inside the system first were killed, and then ones were co-opted, and then right-wing strongmen were empowered to keep the inevitable from taking place. We are likely half-way through a fascinating, terrible century of shakeout, and if you’re some white guy in a cube farm daydreaming about gladiators or some shit—if you think you’re Russell Crowe or Mel Gibson or Kirk Douglas, only with stubble and a taste for Chobani—History is about to slap you upside the head. You’re not an Optimate, and neither am I. Even today’s Optimates should want to avoid this catastrophe; the energies, once unleashed, are unpredictable—Elon Musk should read about what happened to Crassus.

So to all of you men thinking about the Romans, I say: Come on in, the caldarium is fine. For now.

But the water’s getting hotter.