I love owls, particularly Great Horned Owls. I love that they are called “the tiger of the sky.” I love hearing them hoot when I’m in Michigan every July. I have owl paperweights, owl prints, and I’m considering buying this owl tie.

I once tried to purchase a stuffed Great Horned Owl—now illegal—but was prevented when it was revealed that the item was off-gassing strychnine. Left to my own devices, I would’ve done it anyway. That’s how much I love owls.

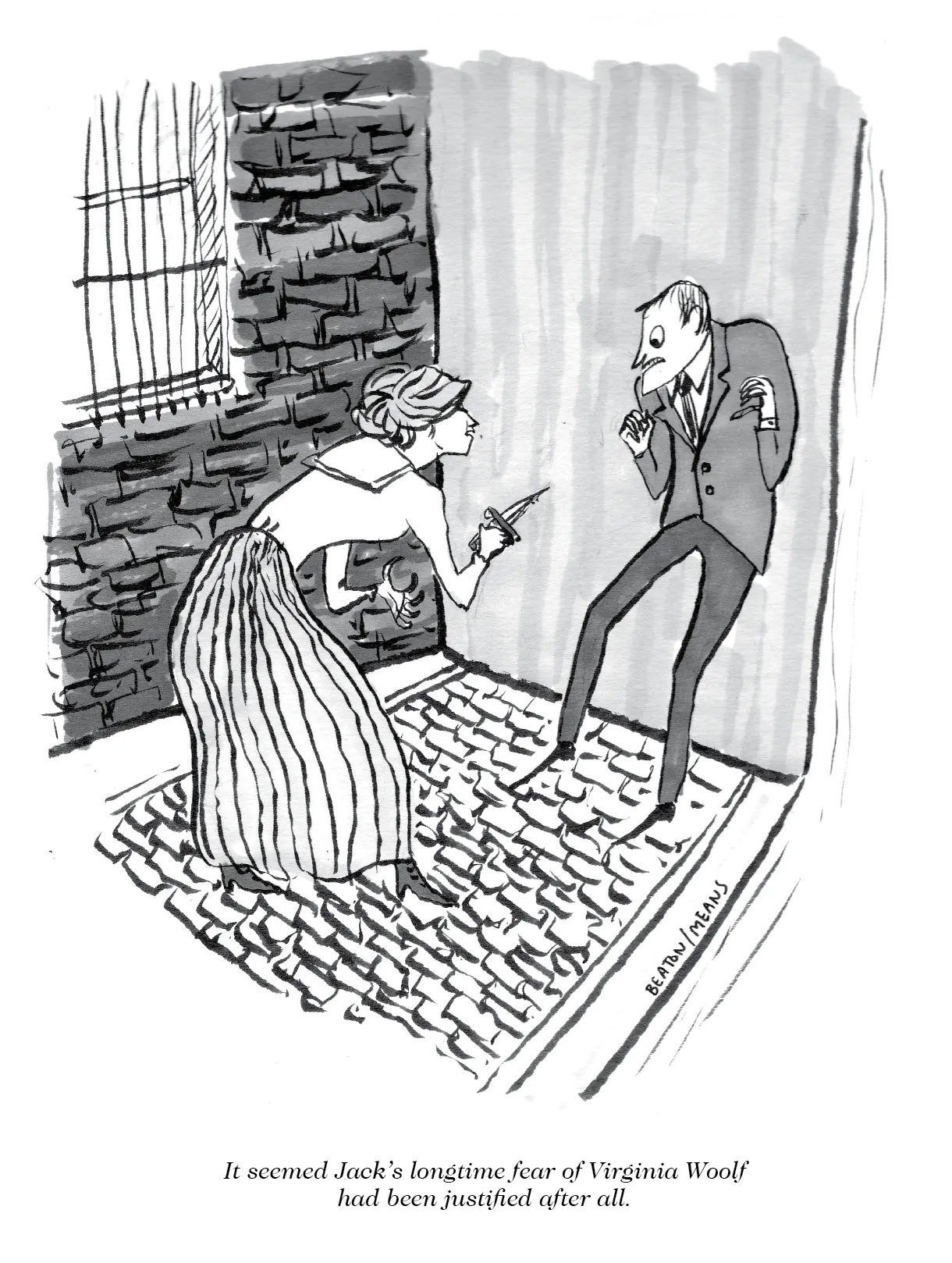

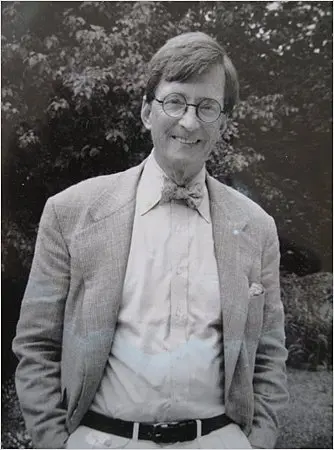

To some, I am an owl—“The Old Owl,” specifically. The mascot of my beloved Yale Record is a waistcoated strigiforme who was transformed by generations of college students from a odd-looking printer’s dingbat into a whole outlook on life—a portly, mustachioed, sweetly lecherous, harmless inebriate, fond of Cutty and dispensing advice no sensible undergrad should ever take. He seems to inhabit one or two alums per generation; for me Owl shone most out of the writer/editor C.D.B. Bryan, the editor of Monocle which I’ve written about here. Courty was fiercely literate, friendly, fascinating in conversation, and resolutely Eastern Establishment, right down to the lockjaw and martinis and the “Godspeed Manatee,” a Navy-surplus boat he’d tool around in. (His son St. George writes charmingly about it here.)

I’d never met anyone remotely like Courty, and haven’t met anyone like him since. I don’t flatter myself that I knew him at all well, but for as much as I knew him, Courty was one of my favorite gents. I like preppies, and Old Owl is the preppiest of totems. It is therefore ironic that his care and feeding fell to me, the great-grandson of a swarthy gentleman who might very well steal your pocketwatch, your girlfriend, or both.

Or maybe that’s why it fell to me. As Yale has become ever-more focused on worldly success, The Owl is a beacon guiding a wise few in the other direction; towards pleasure and conviviality, personal goals not professional, towards showgirls or beefcake, liquor and cheesecake. As the ruling classes have pulled away from the rest of us, they have anesthetized their consciences by becoming more abstemious. Our tech overlords would rather stick needles in their dongs than have a piece of Boston Cream Pie. I don’t know much about Elon Musk, and that’s on purpose, but I bet you he gets up before 5:00 a.m.

Old Owl would not get up that early if you put a gun to his head. The only occasion Old Owl saw that time of day is when the Mocambo was rented out for Ava’s 32nd birthday party, and Frank Sinatra showed up crying and waving a gun.

(I take that back: Owl did occasionally accompany Gianni Agnelli on his early morning dives out of a helicopter into the Mediterrean.)

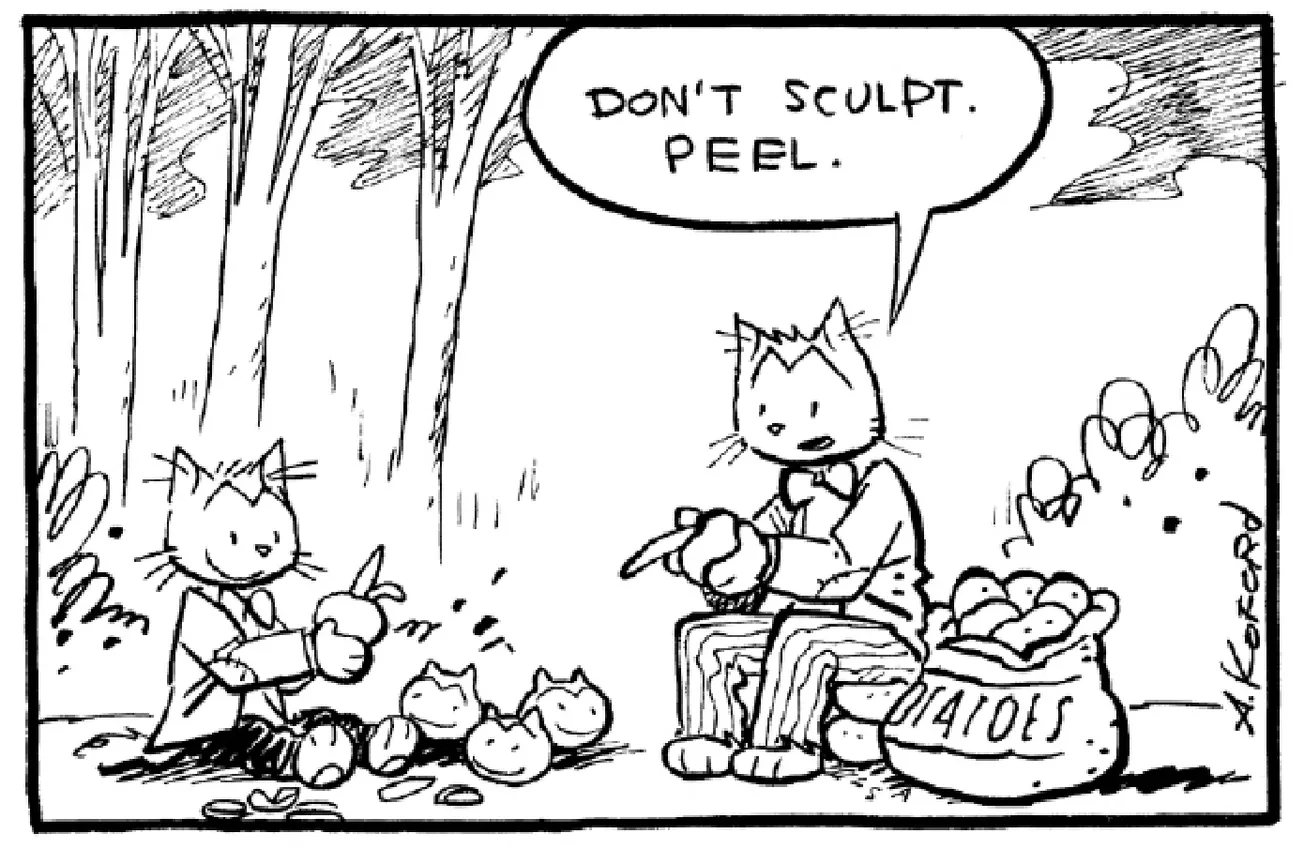

My generation—thanks to my youthful dalliance with the original Demon Weed—tucked a cigar (a Cuban Bolivar, to be precise) into The Owl’s wing-feathers. Yale does not like this, or its lawyers do not, and has asked the students to Bowdlerize my friend Todd Lynch’s charming illustration. But so far we have held firm; in this peculiarly blue-nosed age, we reserve the right to give our guiding spirit any self-destructive habit we choose. There are some early candidates for Owl-dom after I pass away, but all of them are as yet much too responsible and respectible. I am working with all speed to loosen their morality, as Courty did for me, because that’s what Old Owl demands.

So for all these reasons, I loved the story of Flaco, the Golden Eagle Owl that patrolled the skyline of New York City, and who died last week, as we all knew he would, after colliding with a building, or getting poisoned, or getting sick. The point is, he’s dead.

You have probably heard about Flaco. And the reason is, the internet sucks.

Flaco was what newspapermen used to call “a human-interest story,” the kind of thing common to every local paper for 150 years. But because Flaco happened in New York, we all heard about it. I learned about him on Twitter, when two people forwarded me the story in the Times, and then my mom in Chicago forwarded me the story too.

Before writing this, I happened to glance at Defector, the admirable and exceedingly well-done writer-owned experiment in journalism that I subscribe to happily and read regularly. And I noticed that there were two stories about the death of this owl.

Both were well-written, and thoughtful, and I was glad to have them. But I also wanted to take this moment to show how the central promise of the internet—that it would bring more diversity, more types of people writing about more types of things, in different and exciting and fundamentally enlarging ways—has not just been unfulfilled, the opposite has happened. More and more, we see the same subset of people all writing about the same thing at the same time. Back in Courty’s day, there was great cultural sameness in the people who wrote for magazines, but the profusion of magazines themselves, the tastes of each editor, and the needs of each set of advertisers, built in a kind of diversity. Then you had newspapers, which drew not from the Ivies, but from local pools of talent, only some of whom went to college at all. Gay Talese and Courty Bryan came to occupy the same professional sphere, but started out in very, very different places.

Now, we have an intense cultural sameness in the writers, and many fewer outlets besides. Thanks to the internet, writing has become even more of a rich person’s profession. Social media has become a way to translate celebrity into massive, entirely undeserved control of what the rest of us talk about. And because these people must not stop talking or lose their audience, we’ve seen the melding of sports and comedy and movies and dong-injecting and most of all politics into one thing, “entertainment.”

Now, nobody is smart about all of these things, and the quality of the outlet drops down to the lowest competency. I have things to say about comedy, and certain periods of history, and The Beatles—but to thrive on the internet, I need to have an opinion about every bit of brain-lint that passes through. Courty was wide-ranging—he was a novelist and an editor and a crackerjack reporter who, IIRC, broke the story about JFK and Marilyn. But today he’d have to do all those things, and engage with brain-lint like “when the fent cart kills ur slime.”

The internet runs “the discourse,” and as Laura just said to me, “Children, and billionaires who act like children, run the internet.”

Dopey or smart, Flaco or Burisma, it’s all grist for the same mill. Every aspect of the internet has encouraged monoculture, and now that there are fewer and fewer publications available, we rely ever-more on the thoughts and beliefs of a small group of (ironic, headbound, depressive) people all inhabiting a very similar mental landscape. Los Angeles is either a suburb of New York or vice-versa, and I never met more people from Boston as I did in my first year living six blocks from the Pacific Ocean.

And wouldn’t you know it, they all loved “Succession,” and all felt it really explained How We Live Now.

So much sameness. The same schools, the same references, the same slang, the same sense of humor. An owl flies in New York, and we all hear about it—via essays—even if the writer doesn’t live in New York. An editor would’ve sent one of those pieces back—“We covered the owl, think of something else.” That’s what editors are for. Everybody on a place like Bluesky sounds the same to me, and I can scroll for an hour without reading a single opinion that surprises. And so success means feeding those opinions, talking in that one precise language about a limited set of things. The internet homogenizes, and calls it democracy.

You don’t have to be a right-wing douchebag to see that this, too, is killing culture—not just via broken economics, or the unrelenting push from local and regional to a few big institutions, invariably centered in Megalopolis—but also to having one set of slang, one set of references, one set of opinions, all acting as a membership card, people in their 60s talking like they’re 22, because they have to for the joke to land. “Old Man Shakes Fist at Cloud” is a meme, but in a world where a reality TV host/rapist is hawking gold sneakers and is still considered worthy of the Presidency, isn’t the reverse the real problem? A country where nobody knows what the fuck a grownup is? How adults are supposed to act? When does the editor run a blue pencil through Trump? At what point do we all wake up, shake, and think, “Something’s really, really wrong here. Maybe my phone is fucking up my brain.”

It’s not just about “touching grass”—it’s about getting out of the eternal flow of Now This, Now This, Now This. It makes me want to pretend to be a fat little dissolute owl, eating red meat and smoking cigars and making up stories about Frank and Ava, just to escape The Discourse. I still remember a young guy at a job I once had saying in a voice dripping with scorn, “You don’t understand Twitter.” As if Twitter is some great leap forward in human communication. As if Twitter doesn’t suck. No sensible adult should understand Twitter—even before Elon, it was a crime against Humanity, because time and attention are finite, and it talks about trifles, and reduces important things to trifling ones. For the same reason—even though I love owls, you know I do—in a world of like, five decent online publications, one essay on the death of New York’s celebrity owl is enough.

I do not know whether Flaco could’ve survived longer in New Haven, or Sheboygan, or Calabasas, but my instinct is that as a free animal, his chances would’ve been better there. Big cities are wonderful places to visit, but they’re increasingly not meant for people and other living things. And I think that journalism needs similar freedom. We’ll be building localism, freedom, and maybe a few vices—into the new Bystander. Watch this space.