I have been working on my omelette skills of late, and things are going well, thanks for asking. I’ve come to believe that every young person regardless of circumstance should be taught how to cook a good omelette, around the same age they learn to change a tire and how to buy Bitcoin. I have never done the former (I don’t drive), and my accountant is still laughing about the latter, but on omelettes I am certain. The only plank in my platform is that there should be a national program, like conscription in Israel, but for making omelettes. This is a hill I will die on.

Whenever I cook an omelette (and just look at it!) I think of my Dad. Dad did not cook for us often when I was growing up, but one of his “specialties” was omelettes, and I remember them to be delicious. Everything my Dad cooked was delicious—you would kill a person for a plate of his barbequed ribs, and no jury would convict you.

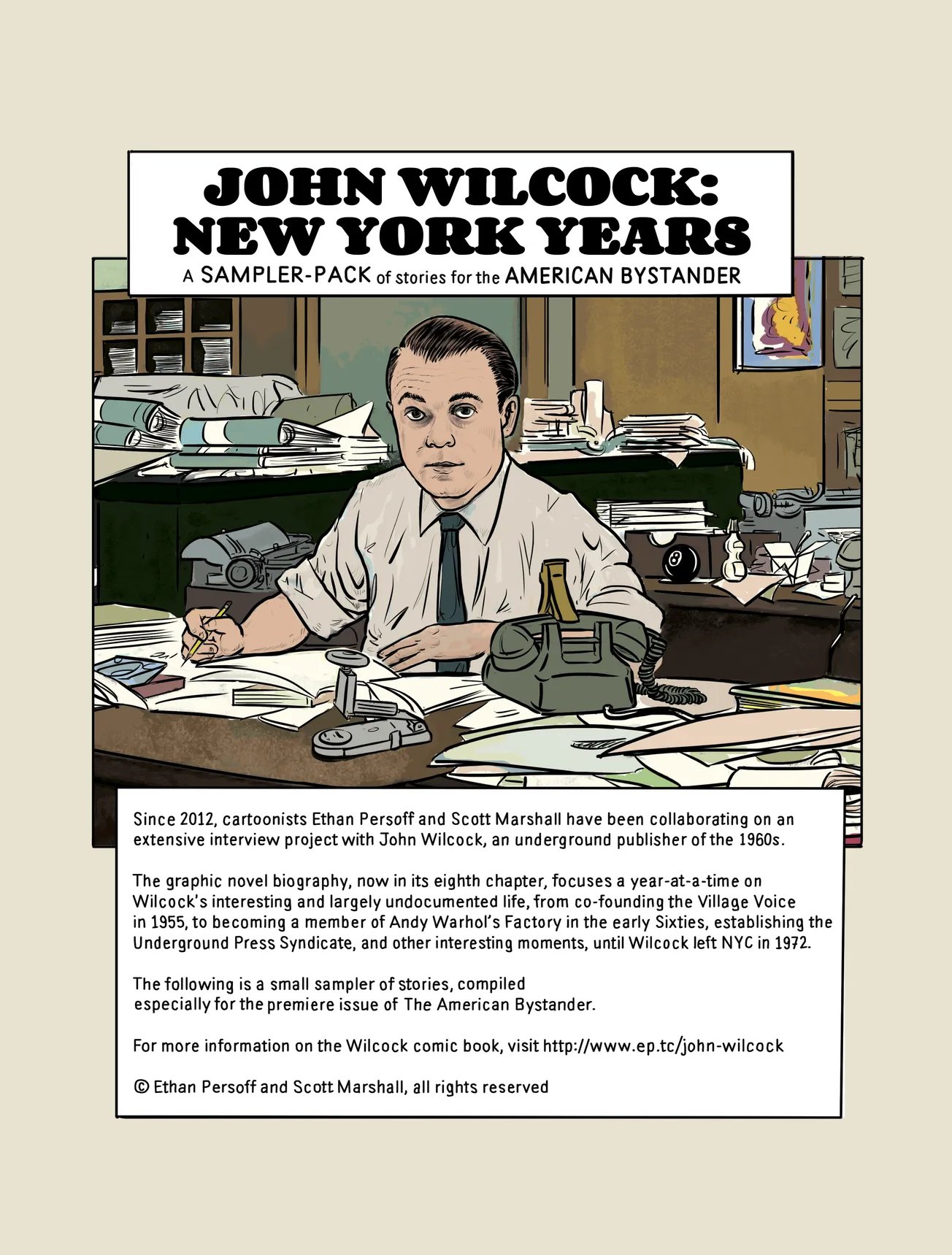

The American Bystander's Viral Load is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Now things are different. Last I heard, Dad is a vegetarian, and while he will make ribs for me on my birthday, he cannot hide his Vegetarian Ick-Face. He is also prone to busting out things like, “Butter will give you a heart attack.”

“Like, if it gets on your skin?”

He frowned at me as if to say, “Better not chance it.”

But back then, in the full-fat and dairy decades, my Dad’s cooking kicked ass. He once made me tapioca when I was sick, and I swear to God it cured me. I think this is because he only cooked when he wanted to. Like on Christmas morning, when he’d make omelettes.

Standing over the sizzling omelette pan Dad would insist that he “had been a French chef” and for a few years, I believed him, until my mother could take no more. “Greg, you were a short order cook in a bar. There’s a difference.” Yes, and I would say that a short order cook is cooler. I think my Dad agrees, because he did not budge. He still won’t. If you know him, next time you see him go up and ask if he was a French chef. He will tell you “Yes.”

This, I believe, is to his credit.

My Dad didn’t lie frequently (or maybe I just haven’t caught him yet) but I can think of two others. The first was, “Yes, I have swum with a Great White Shark.”

“REALLY!?” six-year-old me gasped. You have no idea how heavy a claim this was in 1975.

“Really,” my Dad said. “That’s why I won’t see JAWS. Too many memories.”

I looked over at my mom for confirmation.

“Don’t look at her, she wasn’t there,” Dad said. “This was years before I met her. The summer I spent on Martha’s Vineyard.”

“Ohhhh,” Mom said. In the years since, I have learned that bad acid and perhaps an STI were the primary dangers Dad faced that summer, but out of decorum my mom kept silent. Well, as silent as she could be—my parents have been married for 46 years, and my mother has maintained a fundamental skepticism towards my father which, it must be said, has served her admirably. “Swimming with Great Whites, Greg, huh. How did that happen?”

“Yeah, I was down about twenty feet, and I happened to look over by a bed of sea grass, and there it was. A Great White.”

“You’re kidding me!” I was practically levitating. “WHATDIDYOUDO?”

“Stayed calm, and swam up to the surface,” Dad said. “They don’t want to bother people. Great Whites are frightened of people.” This first part is undeniably true, though the last is perhaps overstating things. Then, elated I was buying it, Dad pushed his luck. “I nodded at him, and he nodded back.”

My mother snorted with laughter.

“Come on, Dad! Tell me the truth!”

But of course he didn’t, and wouldn’t. Lying to children is one of life’s greatest pleasures, and not having children makes me understand this in a way that parents, forced to lie constantly, might be numb to. Sure, I try to lie to my nieces and nephews whenever possible but simply don’t have the time to build up much credibility. My nephew Patrick doesn’t even believe that “Yale practically invented college football,” which is, if not exactly true, absolutely true-ish. It’s miles closer to the truth than what his grandfather told me about the shark.

(Sometime in my 20s, Dad admitted it was a hammerhead.

“A baby?” Mom asked.

“Trish, why do you have to be like this?”)

My Dad’s other great lie was “Lou Brock says bread makes you slow.” He did this because ten was a chubby year for me, and he was concerned I wasn’t eating healthy. Lou Brock, for those of you who did not grow up in St. Louis in the 1970s, was a legendary base-stealer for the Cardinals and, thus, someone whose opinions on personal speed were not to be taken lightly. If Mr. Lou Brock had ever said such a thing…which he had not.

But I bought this completely, and made the necessary dietary changes. For about a week. Then I was back to taking slices of Wonder Bread, rolling them up into balls, and letting the sweet goo slowly dissolve in my cheek. This did not make me fast or slow, but it was better than tobacco, which some of my fourth grade classmates were already chewing, this being Missouri and all.

My mom’s truthfulness setting was the opposite, especially in the years before my stepfather came along. I knew exactly how the sausage was made, even when it came to Christmas. I do not recall ever believing in Santa Claus, though I must have at one point, simply through osmosis? Certainly by age five I knew exactly who bought me what present, and the sacrifices it took for them to get it. “Your aunt Mary went to five stores to get that Steve Austin, so don’t lose that chip in his arm. And don’t draw on his eye, either!”

This was a good thing to know. I never had any use for Santa, and the love of my aunts and grandmothers was much sweeter than the random kindness of some B&E man who was clearly addicted to bread.

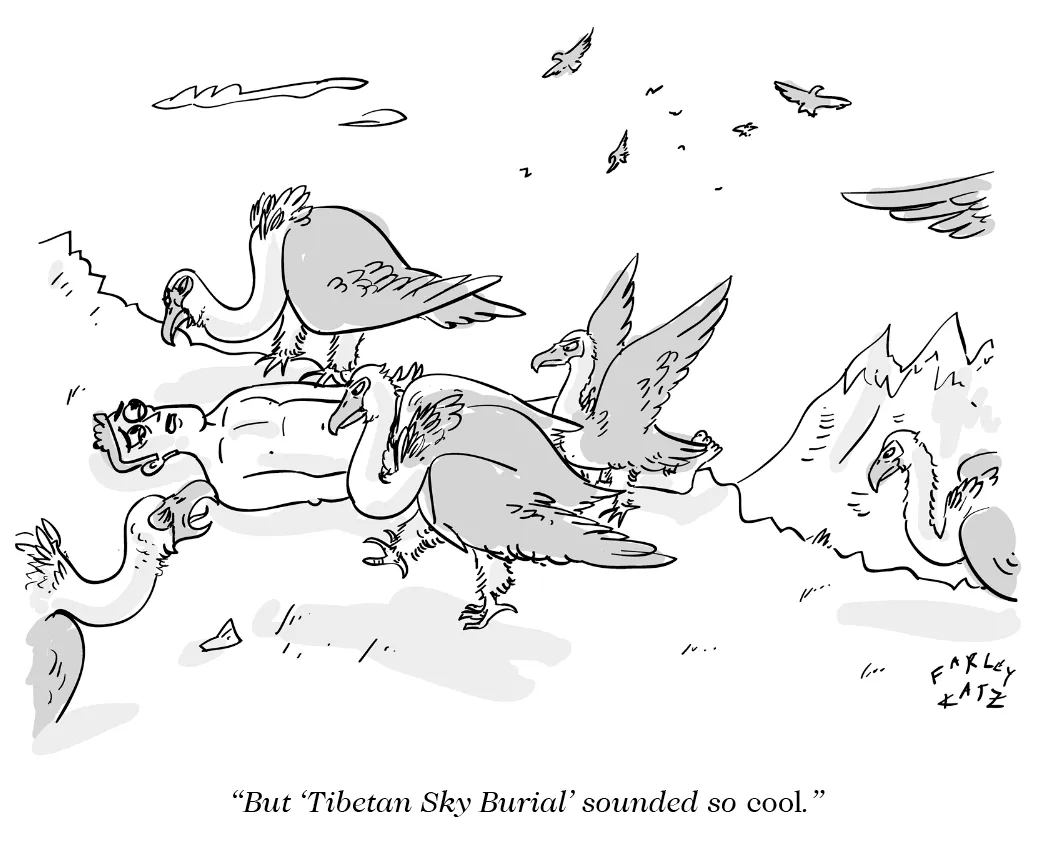

Santa Claus persists not simply as a capitalist tool—the wheels of commerce would spin almost as frenziedly if all those gifts just came from Mom and Dad—but because of what he does for adults. Santa Claus makes an obligation magical. Life is hard, and boring, and what lots of people call “delusion” is precisely what keeps the game going. Like, at this moment, I honestly believe that 500,000 people will read this column, maybe a million. I have to believe that, or else why? People lie to themselves, so can we blame adults for lying to children? Lies to make themselves look good, to keep the family together, to make adult life—which for a lot of people truly sucks—a little more of what they want it to be?

There’s a whole political party with really only one plank in its platform: “Parents should be able to lie to their kids.” Turns out lying to one’s kids—about guns, or COVID, or drag queens, or trans people—is a hill lots of people are willing to have others die on. Some people are so committed to this they’re actively afraid of anything that makes kids able to get information. What kind of weirdo fears libraries?

They needn’t worry; national truthfulness isn’t going to break out anytime soon. We tried that with Jimmy Carter and just weren’t mature enough. So let’s at least return to helpful lies. In addition to convincing me he had studied at Cordon Bleu, my dad told me that people are basically good, and that courage never goes unrewarded. I didn’t need Santa Claus or Jesus Christ, because Mom told me that our leaders were good people trying to do the right thing, and that the U.S. was the best place to live because everybody was equal and would be taken care of, and the rights of every citizen would always be protected. All these are good lies, because when you discover the shitty truth you think, “But that’s the way things should be, and could be, and let’s make them that way!”

So if any kid comes up to me, I’ll tell them a little helpful lie: “If you want to get laid, learn to make a delicious post-coital omelette.” And if they need more incentive, I’ll even resort to the truth: “Use butter.”

The American Bystander's Viral Load is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.