Substack Superstar The Honest Broker just posted a piece about the demise of American magazines, and as readers of this blog know, I am always up for a good obituary.

Ted’s thesis is nicely summed-up in his subhed: “Or what happens when journalism forgets about quality writing.”

If only that were the problem. If only the magazine business could be saved by collecting a bunch of top-flight writers and artists, putting them inside a beautiful package, and as Ted says, “nurturing them and paying them more than peanuts.”

That is my life’s dream. I have spent the last ten years running a magazine predicated on precisely that idea.

It’s called The American Bystander, and I’m sure Ted hasn’t heard of it.

That’s not Ted’s fault, as you’ll read below. Nobody hears about any magazines these days.

Editorially, Bystander has been a huge success. But publishing-wise, it’s only gotten harder, and so my GM and I are in the middle of changing it from a for-profit humor magazine regularly praised in The New York Times, to something more like the ballet. Truly profitable print magazine publishing is nearly impossible for anything but niche publications with built-in ad bases. I’m sure Cigar Aficionado is doing just fine, and while The New Yorker may continue to shrink, I suspect VOGUE will perk along in some form until the Sun explodes (2-3 billion years, according to Google, which may be hallucinating).

(Humor magazines are a type of general interest magazine, and because they please readers rather than advertisers, they have never really worked after the demise of the newsstand biz. I’m happy to talk more about this—or anything else—in the comments, but I want to cover as much ground as possible in the post.)

Corporate short-sightedness is only part, and the less depressing part, of the story. Both readers and the writers and artists themselves have been trained by the larger culture to behave in ways that make what Ted is suggesting nearly impossible to pull off.

Trust me, I—and $100,000 of my dearly beloved personal dollars—have tried it.

Let us begin with the easy part: how is the business messed up? What mistakes have they made?

• • •

When you’re running a print magazine, you’re offering two things: access to content, and a relationship with the reader.

Since the advent of the internet content—which used to be curated, and purchased for money—is now common, unfiltered and free. For example, it just took me five seconds to pull up Gay Talese’s wonderful essay for Esquire in 1966, “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold.”

How can you compete with that? Can any new magazine be so much better than all the stuff you can get on the web for free?

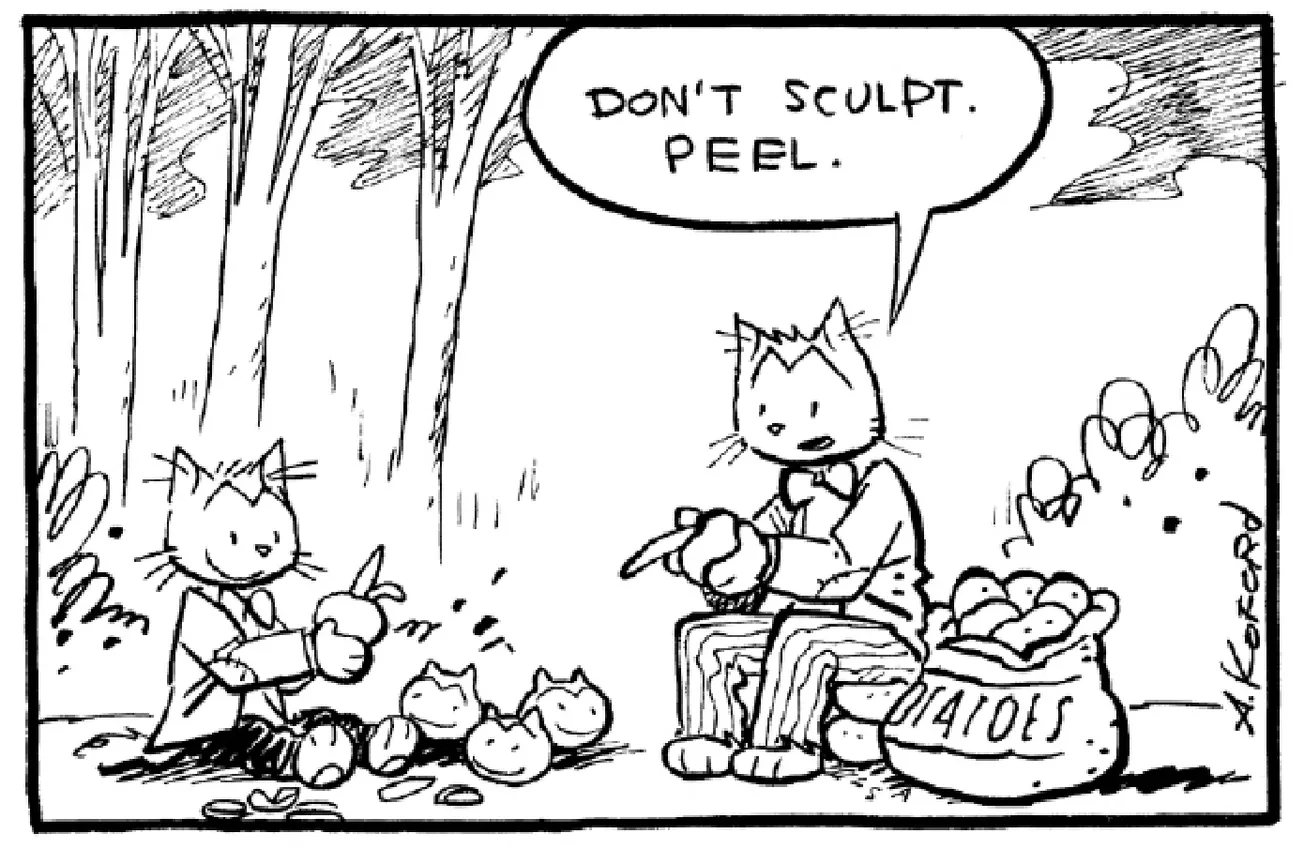

Closer to home, I’m going to type “Sam Gross cartoon” into Google…and there’s all the Sam I could want. And Sam was absolutely adamant that his material shouldn’t be scanned and shared: “Exposure? You can die from exposure.”

For any cartoonist under 50, there would be even more free stuff.

The moment a piece of content is digitized, your pricing power on it is zero.

Free sharing—which is what the internet is designed to do—is diametrically opposed to commercial publishing. And it’s getting worse; over the last ten years, fewer and fewer people are willing to pay for content. Packaging, yes; content no. People have always loved The American Bystander as a product, just as they love the Sgt. Pepper Super Deluxe Edition. The problem is, you can charge $20 for the former, while the latter makes you six times as much money. The philosophy behind mass market magazines, and their present-day economics, are utterly at odds with each other.

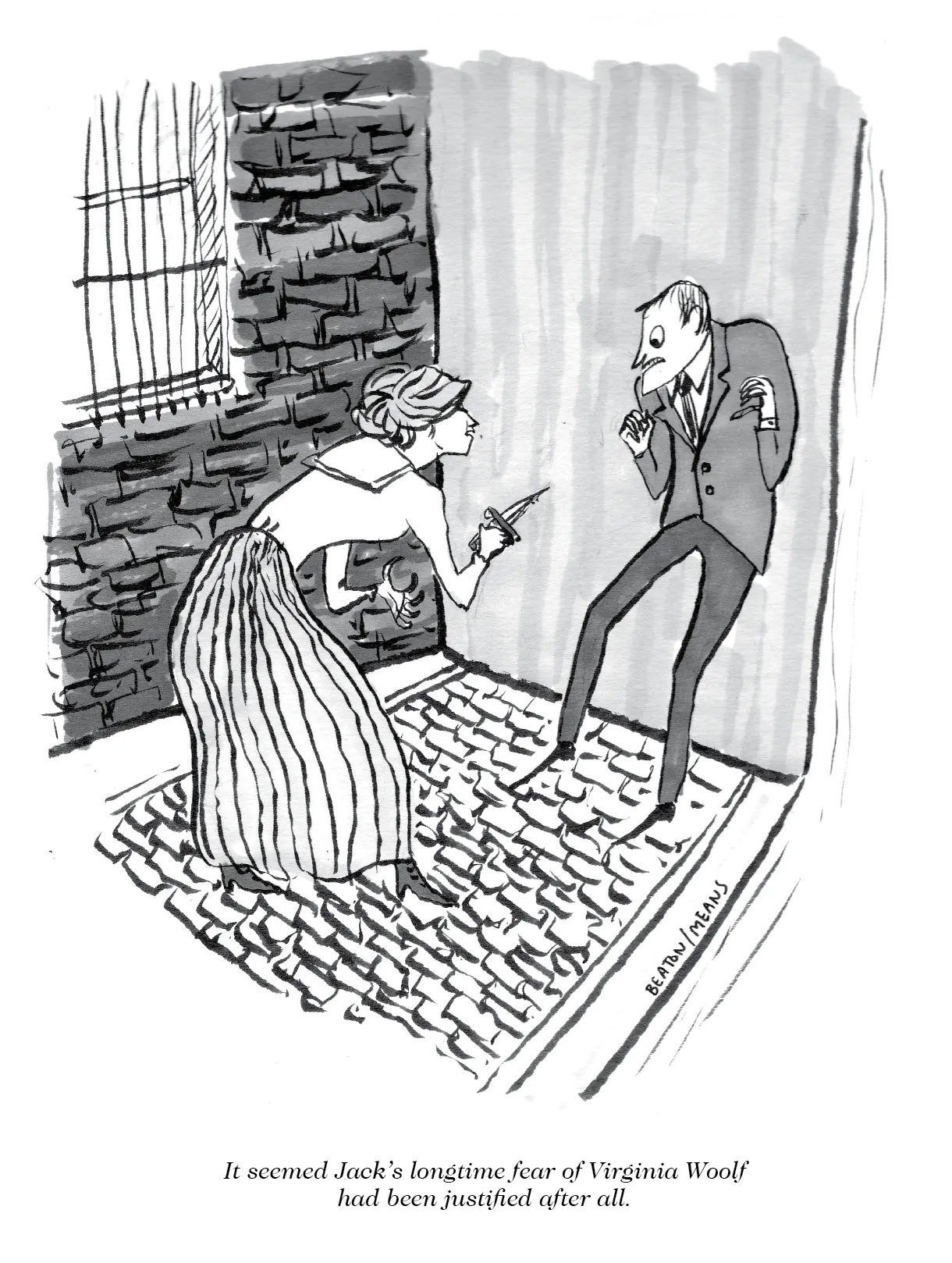

With the content marked down to zero, the only thing you have left is the relationship, the “idea” of the magazine in the reader’s head, and what they think it means about them. Is The New Yorker this week’s articles, or is it a kind of Proustian madeleine for America’s ex-English majors? Is it whatever they’re saying about Tim Walz, or memories of a framed poster of Steinberg’s famous cover you had in college?

Hold events. Sell merch. Monetize that relationship. The New Yorker has its Festival of Ideas, and we have our new Etsy shop.

But even with all The New Yorker’s advantages, it remains to be seen whether sufficient numbers of today’s 25-year-olds love the print version enough to keep it going in 2040. Last week my GM got on Zoom and said, “LOOK AT THIS—40% of Bystander’s readers are over 65!”

Uh-oh.

Getting back to Eustace Tilley, my guess is, now that S.I. Newhouse is dead, sooner or later they’ll split the print mag off into a foundation—a 501©3, as we’re doing—and license all the back matter, or sell it to Getty, or someone else who makes a cold-hearted calculation based on the number of Hinge ads they can sell against the traffic.

Was this future inevitable? Were print magazines cooked the moment browsers got good enough to show layouts? No.

In the early 90s, when I prowled the carpeted corridors of places like Scholastic and nearly became the editor of SPY, within the magazine business there was a lot of conversation around paywalling and micropayments, basically ways to replicate conventional publishing in a new digitized age. Neither were implemented, because the magazine business would’ve had to present a unified front. Capitalism discourages that. And also they would’ve had to entirely switch their mindset from “we make money by pleasing twenty big-ticket corporate advertisers” to “we make money by pleasing one million readers.”

This was never going to happen.

Then there is the distribution problem. Both newsstands and bookstores had been in decline since the advent of TV, but the web really dealt them a death blow. I’m not judging, I feel more affection for a good bookstore than my mother’s womb. And yet…there is Amazon, with its cheaper prices and instant gratification.

When I moved to Santa Monica in 2005, there were four bookstores within walking distance of my apartment, and a large outdoor newsstand featuring hundreds of publications from all around the world. Now, they are all gone. I used to see people sitting on the Third Street Promenade, drinking coffee and reading magazines. Now, everybody’s on their phone. (They are still drinking coffee, and that should tell you something.)

I love magazines, but where do I even go to buy one? How do I find out about new ones? These are basic business problems that the industry simply refuses to solve.

When I was a consultant for Hearst New Magazines back in the mid-90s, I remember telling a guy that Hearst should use the web to create a virtual newsstand. Create a sales and promotion portal direct to their readers.

“If it works,” I said, “then charge other magazine companies to use it. And eventually book publishers, too. You have millions upon millions of loyal readers every month; drive them to a website, and there are bunches of ways to get rich.”

This, too, was never going to happen. All these companies were in New York; they looked around and saw newsstands. More than that, the people who ran the newsstands would have immediately blacklisted any big company who tried to use the web to circumvent them. At best, all Hearst mags would’ve disappeared off the racks; at worst, people would’ve gotten their legs broke.

You think I’m kidding? In 1997, when I tried to get a parody of The Wall Street Journal on the newsstands at LaGuardia, the first thing a magazine consultant said to me was, “I assume you have the customary $10,000 in unmarked bills?”

Still, if there’d been a Hearst or a Luce or even a Hefner in the bunch, he would’ve invented Amazon. And things would be massively different today.

Mass-market magazines are profoundly corporate entities. They have to be; the way magazines are published is hugely capital-intensive. And in corporations, the executives and their perks get cut last. Low pay rates, then user-generated content, and now AI are all attempts by a business desperate to maintain their office space in midtown Manhattan. Writers may not make much money, but executives at big publishing companies sure as shit do.

With Bystander, I’ve kept our overhead brutally low, and I use that adjective on purpose. For over a decade I’ve handled everything—assigning, editing, some writing, house copy, design, layout, overseeing production and customer service. Now I have my GM Laura to help with some of it, but for most of that time, it's been a one-man band. This was done so I could push through as much money to the contributors as possible. Let’s talk about them next.

• • •

Ted (and many others) tout Substack as a possible replacement for the print culture we’ve lost. Though I’m politically left-wing, it seems to me that Bari Weiss’ The Free Press is the closest thing to what Ted is talking about.

But there’s a real barrier to this happening. Two actually.

The first is Substack’s finances. Maybe they can keep this up, maybe not. But even if they can, a one publisher ecosystem is a catastrophe waiting to happen. You think censorship was bad in 1957? Look at how Musk has changed Twitter. People like Hearst were assholes, but they weren’t reaching down to individual readers and dogpiling them for Wrong Thought.

The capitalist web promises limitless choice until it suckers us all in, then it whittles everything away until you’ll take whatever we give you, and better smile as you pay us more for it.

So that’s one barrier. The second is writers and artists themselves.

Bystander has published close to 400 writers and artists since 2015. The vast majority of our most devoted contributors have been over the age of 60—in other words, people who were firmly embedded into legacy media before the introduction of the Apple MacIntosh.

The Mac, and the PC revolution in general, democratized the ability to make content and spawned the ‘zine revolution, a truly glorious time for print. Then the web, and later social media, democratized the ability to distribute content. Unlike zines, which spawned infinite stylistic variations, social media has given us vast restrictions in format—”you can say anything you want, as long as it fits within 140 characters.” The first part of the digital age was about making the old forms easier, and that was great; the second was about training people to work within the arbitrary boundaries of the tech. The 140-character thing wasn’t a creative choice, nor what the audience wanted, but simply a tech-side concern. Coding is driving our culture, and that’s fucked up. To some degree people are not reading magazines because they are on social media; and social media is both very free and incredibly narrow. What it trains you to want is…more social media. We now see the world in terms of memes. This isn’t progress.

Writers and artists used to need magazines to get their material seen. The moment that was no longer necessary, the power of magazines over their contributors began to wane. Now, it is basically nil, or feels basically nil—there is a benefit to being associated with an institution, but in the minds of younger creators it’s counterbalanced by the possibility of being associated with something they don’t like, and also the dilution of their “personal brand.”

To use Ted’s analogy of the Los Angeles Lakers: in the 1980s, the individual Lakers were assisted by a perception of the group —”Showtime”—and that institution’s storied history. One or two individual players might be big enough stars to monetize their success (I’m thinking of Magic and Kareem) but the rest of them, even wonderful talents like James Worthy, needed that team to make the maximum money over the course of their careers. Worthy might’ve gotten one big contract with, say, the Milwaukee Bucks, but over his career he almost certainly made more, and played longer, by being part of the Lakers, and specifically the Showtime Lakers.

Writers and artists today are free-floating individual players endlessly playing on one broke team after another, with the owners of the arena making all the money.

Is it possible for other collections of writers and artists to use The Free Press model to create digital approximations of mass-market magazines on Substack? Only if you define “mass-market magazines” in the blandest, most narrow way possible, within the boundaries of Substack’s tech. There’s no design. There’s no big, sumptuous advertising. There could be a strong editor, and strong voicey house copy—like Hayes’ Esquire or Stan Lee in Marvel comic books. But you couldn’t hold it together. Every day there would be the example of people like Matt Taibbi or indeed Ted himself. “Why build this group brand, when I can build my own? Can I really afford not to try?”

Bystander’s main tool to solve the distribution problem was online publicity, and the online publicity plan was having its big staff—80 or more contributors in every issue—tweeting out to their followers. That didn’t happen. The older people who got why being part of an institution can be helpful, weren’t heavy social media users. Even when they knew how to use Twitter, they didn’t have big followings. And the middle-aged and younger people…they wanted to promote their self-published children’s book, not “your” magazine. And great print humor magazine material doesn’t always translate well to Twitter, land of memes.

And after Musk took over, forget it.

I paid as much as I could to as many people as I could, out of my own pocket, but eventually I too had to think of myself as a solo act, economically speaking. That’s the world the tech overlords—all ensconced within their corporations—have bequeathed to we lone-wolf creatives, and it will persist, because it works for them, even if it doesn’t work for us. Also, people really love playing the lottery…maybe that cartoon will be the one that goes viral? You never know, unless you post it…

• • •

The final aspect of Why Magazines Are F*cked is, sadly, readers.

More people spend more time reading more stuff than ever before, but it’s all for free, on the internet.

This behavior has been beaten into us, one dopamine hit at a time, by a few big tech companies which have gotten very rich as a result.

This is not going to change. In fact it’s going to get worse.

There’s also infinitely more media to choose from, and it’s a rare person who would pick a print magazine—no matter how wonderful—over all the movies, TV, podcasts, satellite and terrestrial radio, and video games that are now available. In addition to being more exciting, all those things are much more convenient, and often cheaper. For most of them, you don’t even have to leave your bed.

This is also not going to change. It is also going to get worse.

But using the Bystander’s special publishing model, we only really need 5,000 subscribers to become as timeless as the Sun. In a country of 350 million people, I like our odds.

And there are other glimmers of hope. Since 1995, I have worked with students at The Yale Record humor magazine, and year after year, by God and Harold Ross do they love print. They don’t plan on doing it for a living (thank heavens) but they love the format. They love its permanency, its flexibility, its realness.

So I think there will be readers for print magazines, humor and otherwise, for the foreseeable future. But how big will that group be? Will they be willing to pay the freight? And how will they be reached?

I’m tempted to write, “Who knows? Anything can happen!” but the demise of print in America argues against that. Who knew? Everybody—they could just make more money in the short term by letting it die. Can anything happen? Well, theoretically, but what’s likeliest is whatever Mr. Cybertruck thinks is a laff.

That doesn’t mean we don’t try for something better; The American Bystander has been a wonderful, though unprofitable, for-profit magazine. And it will be even better when it’s supported by grants and tote bags. But if we want to avoid the mistakes that have doomed Big Print, we have to be brutally frank about how this has all occurred. Greedy, short-sighted corporations? Strike one. Writers and artists who’ve bought the “exposure” lie? Strike two. And readers who won’t pay for content? Strike three, and we’re all out.

Next batter up. ◊

For reasons known only to his therapist, MICHAEL GERBER edits and publishes The American Bystander. Sample issues can be found here. GM Laura Fox says, “If you love magazines, go to our new Etsy shop, or else you hate magazines.”